[ad_1]

As early cameras began spreading out from Europe in the middle of the 19th century, photography became an increasingly powerful medium for obtaining and disseminating information about the wider world.

People and places that had previously only been captured through art or in written accounts could suddenly be depicted with unprecedented accuracy. With this new medium, local administrators and commercial photography studios, in cities from Hong Kong to Calcutta, helped build a richer visual history of life in the 1800s.

CNN asked the show’s curator, Christine Barthe, to pick 10 images from the collection and explain what they reveal about the places — and times — they were taken in.

View of the Holy Shrine and the city of Mecca, present-day Saudi Arabia, 1881

One of Muhammad Sadiq Bey’s 19th-century images of the Great Mosque at Mecca, the holiest religious site for Muslims. Credit: Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

As well as showing the condition of the mosque and the architecture of Mecca at that time, this photograph was included in the exhibition because it recognizes the work of a pioneer who “deserves a better place in global history of photography,” Barthe said.

“We don’t know so much about the history of photography outside Europe and the USA, so many of these first important photographers aren’t too well known,” she explained in a phone interview. “Sadiq Bey is a good example of this. You won’t find his name in a traditional history, so (his inclusion was informed by) the simple idea of shining a light on his work.”

Dead crocodile on a boat in the Nile, Egypt (1852)

Ernest Benecke’s image of a dead crocodile on the deck of a boat in the Nile. Credit: Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

Part of a new breed of explorer-photographers, Ernest Benecke extensively documented his travels across the Mediterranean, North Africa and the Middle East.

But rather than simply capturing the architecture and landscapes he encountered, the Anglo-German photographer turned his lens on daily life and local cultures to produce what Barthe called “poetic and unexpected” pictures.

“The atmosphere seems a little more ambiguous or mysterious,” she said. “Benecke’s pictures are different from the usual ones (coming out of Egypt at the time) — of women carrying water pots or palm trees.

“It’s Egypt, but it’s not the postcard Egypt.”

A street, Canton (present-day Guangzhou), China (1870-1890)

The long exposure times of early cameras made it difficult to capture street scenes. Credit: Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac / RMN Grand Palais

Lai Afong is one of the most important figures in the story of early Chinese photography. In addition to opening one of the first Hong Kong portrait studios in 1859, he also produced a large body of landscapes and cityscapes.

Lai’s street photography is particularly notable, as the long exposure times of early cameras made it difficult to capture busy scenes without blurring the images.

“This picture is special because it’s vertical, and the idea of taking pictures in the street with all this movement … gives us the feeling of a very modern photo,” said Barthe. “It could be a picture made in the 20th century.”

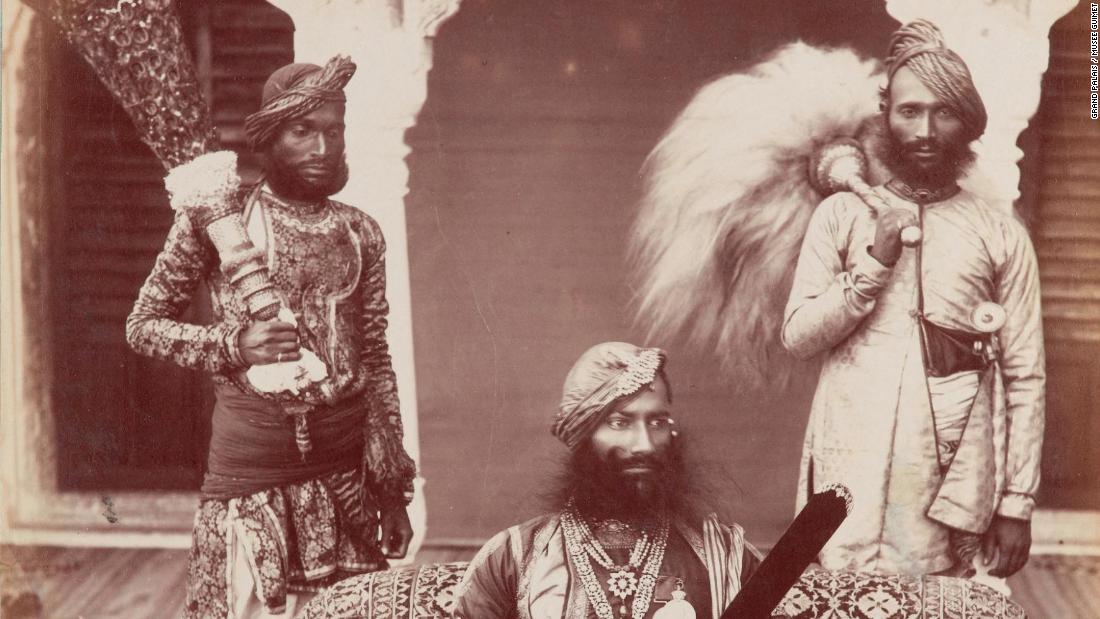

Portrait of Sir Pratab Singh with his entourage, India (1882)

A portrait by the pioneering Indian photographer Lala Deen Dayal. Credit: Grand Palais / Musée Guimet

This portrait, like many from the period, was created using a process known as albumen print, which uses egg whites to bind chemicals to paper. But unlike many 19th-century portraits from India, it was taken by a local photographer, Lala Deen Dayal, who set up a number of commercial studios and served as an official photographer for British officials and Indian royals alike.

The inclusion of Dayal’s work in the exhibition helps subvert the idea that Asian photography’s early history was dictated by colonial elites, Barthe explained.

“This image shows that the way local and European photographers took pictures could be quite similar,” she added. “In this case, the portrait shows the powerful and wealthy — a way to show the power of the (Indian) people.

“It’s interesting to compare (with studio images of wealthy Westerners), because sometimes, when the goal is the same, the same kind of pictures are produced.”

Portrait of Emir Abdelkader, Paris (1865)

Emir Abdelkader, a key figure in the Algerian resistance, photographed by Jacques Philippe Potteau in Paris. Credit: Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac / RMN Grand Palais

This portrait, taken in Paris in 1865, was included in the exhibition not for its creator, the French anthropologist Jacques Philippe Potteau, but for its subject, Emir Abdelkader. As well as being a key figure in the Algerian resistance to French rule, Abdelkader was a theologian and philosopher with a keen interest in photography.

His passion for the medium saw him pose for a number of the day’s great portraitists. He is also responsible for one of the earliest known essays on photography by a Muslim thinker.

“He had a very positive attitude towards photography and he wrote about the question of photographic appearance,” Barthe said. “It’s quite interesting to compare this with the fact that he was often photographed (himself).”

The Andes, likely Peru or Bolivia (1849)

One of the earliest known photographs from South America. Credit: Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

One of the earliest pictures in the exhibition, this image of the Andean Mountains has been attributed to the American photographer Robert H. Vance. Known for his later images of the California gold rush, Vance opened a number of early photography galleries in the US and Chile.

The images were made using the first ever commercial photographic process, known as daguerreotype, in which mercury vapor was applied to a sheet of light-sensitive, silver-plated copper to leave a sharp impression of the scene or subject. Surviving items are both rare and highly delicate.

“It’s really a unique picture. When we bought it at auction, I realized that I’d never seen such an example of (daguerreotype photography),” said Barthe. “It’s one of the first known pictures of South America.”

The Prambanan temple complex, Yogyakarta, Indonesia (1889-90)

In what Barthe calls “a very early example of a selfie,” photographer Kassian Cephas can be seen standing by the temple entrance. Credit: Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac

Look closely at this image of a Hindu temple and you’ll see mustached photographer Kassian Cephas standing by the entrance.

This discovery meant that the previously unattributed photograph could finally be credited to the Indonesian court photographer and portraitist, who widely documented the cultural heritage of the island of Java.

Although Cephas would likely have relied on his assistants to operate the camera, this can be considered “a very early example of a selfie,” Barthe said.

“It’s not easy to take this kind of picture using the collodion (process),” she explained, referring to a photographic technique also known as the “wet plate” process. “You had to operate the camera with somebody’s help, to set up the tripod and glass (plates), so he may have organized the frame and had someone help him as he climbed the stairs.”

The Maharani of Nepal and her ladies-in-waiting, Nepal (1885-1894)

A rare 19th-century image from Nepal, which was barely documented in the early era of photography. Credit: Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac / RMN Grand Palais

Around 1882, British photographers P.A. Johnston and Theodore Hoffmann founded what became one of the largest commercial photography studios in India. Johnston & Hoffmann produced a range of albumen portraits depicting the people of various Himalayan regions, including Sikkim and Tibet.

The above image was taken Nepal, a remote area that was barely depicted in the early days of photography. There remain many questions around the photograph’s origins.

“This was not made as an ethnographic record — it looks more like an official portrait,” said Barthe. “Johnston & Hoffmann made an album on some of the important people of Nepal, though (the images) are very rare.

“It doesn’t look like a commercial project. It could have been a special request from the Nepalese court, but we don’t have many details.”

Portrait of a young woman, Ethiopia (1885-1888)

A photographic portrait by French explorer Jules Borelli. Credit: Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac / RMN Grand Palais

French explorer Jules Borelli produced detailed illustrated diaries of his travels in Ethiopia, where he often photographed people from the Amhara, Oromo and Sidama ethnic groups.

This albumen image stood out to Barthe because of the young woman’s “mysterious smile.” Unlike the more formal or ethnographic portraits of the era, the subject appears relaxed, changing the mood of the image.

“We can see some kind of relationship between the the photographer and the person being photographed,” said Barthe. “(Her smile suggests) that there is some kind of complicity with the photographer, or something funny happening, though we don’t know if it’s ironic or something else.”

Panoramic view of the Port of Kobe, Japan (1870-74)

An early photograph of the Japanese port city of Kobe. Credit: Musée Guimet

This diptych of the harbor at Kobe, taken shortly after Japan opened itself to the world following decades of isolationism, shows a city on the brink of huge change. The panoramic image’s creator, Ichida Sota, was one of the first commercial photographers in the country, having opened a studio in Kyoto in 1867.

Perhaps more notable than the picture itself, however, is the decorative border. According to Barthe, it shows how early photography was merged with Japanese design in a unique way.

“We have this album with a golden decoration, and we have another one that can be unfolded that also has a very decorative mounting — many different types of photographic objects,” she added. “They show how Japanese taste changed and completely transformed these pictures.

“In other parts of the world, like India, we see a kind of transformation of photographs with traditional techniques (such as painting over images), and Japan offers a very good example of this.”

[ad_2]

Source link