[ad_1]

Sean Yoes

AFRO Baltimore Editor

[email protected]

The United Mutual Brotherhood of Liberty

“As slavery grew to a system and the Cotton Kingdom began to expand into imperial white domination, a free Negro was a contradiction, a threat and a menace. As a thief and a vagabond, he threatened society; but as an educated property holder, a successful mechanic or even professional man, he more than threatened slavery. He contradicted and undermined it. He must not be. He must be suppressed, enslaved, colonized. And nothing so bad could be said about him that did not easily appear as true to slaveholders,” wrote W.E.B. DuBois, in his 750 page essay, Black Reconstruction in America: 1860-1880, first published in 1935.

DuBois, one of the most important public intellectuals of the 20th century, wrote extensively and profoundly about Reconstruction in America, one of the most complex eras in the country’s history. But, if understanding the impact of Reconstruction on the former Confederacy is complicated, trying to discern the implementation of Reconstruction within border states like Maryland seems infinitely more nuanced.

Governance by the Radical Republicans and the Black franchise paved the way for Black political victories throughout the South. Many historians cite about 1,500 Black officeholders elected during the Reconstruction Era. But, virtually no Black men won political office during Reconstruction in Maryland and the state’s Black citizens were not afforded the same federal protections during the era as Blacks in other Southern States. Further, with Democrats in charge in Maryland, the Black vote was in constant peril during Reconstruction and after.

“When the Democrats got firm control of state government, they then began the effort, serious effort to disenfranchise Black voters in Maryland. This led to a series of efforts to change the State Constitution, to impose property requirements, literacy requirements and the like, most of which…had provisions that protected White voters,” said Prof. Larry S. Gibson, University of Maryland School of Law and author of Young Thurgood: The Making of a Supreme Court Justice. “But, they were defeated. They were defeated…through a combination of forces. Major players in the opposition were the early Black lawyers, they were very aggressively involved in organizing voters to vote against these provisions.”

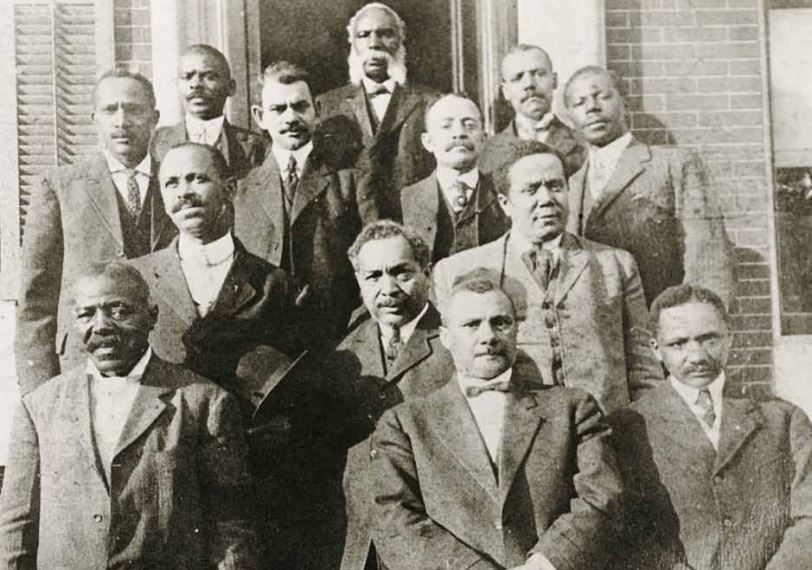

Gibson and other historians point to one man as the central figure in crafting the platform for the first Black lawyers in Maryland; the Rev. Dr. Harvey Johnson, the pastor of Union Baptist Church in Baltimore, the most influential Black church in the city at the time. In 1885, it was Johnson who brought the lawsuit that broke the color barrier for Black lawyers, which ultimately led to the admission of Everett Waring, to the bar of the Maryland courts. Waring graduated from the Howard University School of Law with honors in 1885. And it was Johnson who recruited Waring to Baltimore. That victory led to other Black lawyers being admitted to Maryland courts, due to the work of Johnson and the organization he founded, “The Mutual United Brotherhood of Liberty.”

The founding group included Johnson and five of his fellow clergymen and close confidants: Ananias Brown, William M. Alexander, Patrick Henry Alexander Braxton, John Calvin Allen and W. Charles Lawson.

The group was a forerunner of the Niagara Movement, which led to the formation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

“The organization used the courts and coordinated community protests to challenge Supreme Court decisions that hastened the advent of Jim Crow, expanded educational opportunities to Black children, opened the bar to Black attorneys, and defended laborers re-enslaved on a Caribbean island by a U.S. based company,” according to the book, A Brotherhood of Liberty: Black Reconstruction and Its Legacies in Baltimore, 1865-1920, by Dennis Patrick Halpin.

The Brotherhood specifically paved the way for the earliest incarnation of Black super lawyers, men like Warner T. McGuinn, W. Ashbie Hawkins (a hero to a young lawyer named Thurgood Marshall), Hawkins’ law partner George McMechen and Harry Sythe Cummings, the first Black man elected to office in Maryland.

Early in the 20th century, these men and others were the architects of several groundbreaking legal victories that served as a national blueprint for legal battles in the early Civil Rights Movement. And Baltimore’s Black lawyers were integral in protecting the Black franchise against strong challenges to the state Constitution in 1904, 1908 and 1910.

[ad_2]

Source link