Born in Harlem in 1930, Faith Ringgold became part of the New York neighborhood’s fabric as a painter, writer, sculptor, and performance artist in the ’50s. Her politically engaged work has taken many forms, including visceral styles of painting—typified by American People Series #20: Die (1967), which was displayed next to paintings by Picasso in the recent Museum of Modern Art rehang—and story quilts such as Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima? (1983) and Tar Beach (1988), the latter of which Ringgold made the subject of a celebrated children’s book. The many facets of her career will be the focus of a survey exhibition scheduled to open at the New Museum in New York in fall 2021.

Denver native Jordan Casteel was born in 1989 and now resides in Harlem, where she has emerged among a new class of figurative painters with a focus on portraiture. Her first gallery show was in 2014, and she was an artist in residence at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 2015. This past February, her first solo museum exhibition, “Within Reach,” had a brief run at the New Museum before the coronavirus pandemic shut it down—though the show reopens September 15 and will remain on view into January 2021, with some 40 paintings of Casteel’s friends and family members as well as strangers in her neighborhood with whom she initiated conversation.

Ringgold and Casteel joined ARTnews in July for a videoconference to discuss the legacy of Black artists, how the pandemic has affected them, and swelling waves of Black Lives Matter protests in the streets.

Faith Ringgold, Black Light Series #12: Party Time, 1969.

©2020 Faith Ringgold / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, Courtesy ACA Galleries

ARTnews: What are your earliest formative memories of experiencing art?

Faith Ringgold: I’ve been doing art since I was a child. My mother always made sure I had art supplies. My father bought me my first easel. I did it a lot—because I had asthma, my doctors did not want me to go to school during kindergarten and first grade. They were afraid that I would catch something. But then finally I went on a steady basis, like, from second grade, and we had art every day in school. I loved it.

Jordan Casteel: This is perfect, because my earliest formative memory was reading Faith’s book Tar Beach. I was obsessed with it. My dad tells a story that he was on a mission to find one of the original prints from that book and he gave it to me when I was young. That was my first artwork. We also had a lot of prints in the house, from Romare Bearden and Hale Woodruff. I knew of Charles White. My mom had an Emma Amos painting in the house. So I was aware of those artists, and that was my earliest understanding of art in a historical context. I felt like I lived with Faith Ringgold, with Romare Bearden. That was the visual community I knew, and it gave me a sense of belonging and a desire to tell stories in the way they were.

Faith Ringgold’s first children’s book, Tar Beach, tells the story of a character named Cassie in 1930s-era New York who flies around the city from the “tar beach” of her Harlem rooftop with help from the stars.

Courtesy Penguin Random House.

ARTnews: What about Tar Beach and Faith’s work in general was most important to you at the start?

Casteel: To have a representation of a young Black girl as the central character in a story was the main thing I identified with. Visually, I’ve always been really drawn to color, and the illustrations really captured a sensibility and a visual longing I always had. My mom says as early as six months, I had a keen fascination for the color of cartoons. I would take blocks and put rainbows together. Particularly in Tar Beach, the way that colors are used and the movement of the characters—I was really drawn to that. And it was a story of a Black family that was similar to mine. I felt like the adventures I had as a child were represented in a story that felt like my own.

Ringgold: I love children’s books.

Casteel: I could feel that. I felt like you were speaking to me, as a three-year-old—I felt like you were telling my story back to me.

Ringgold: That’s what I was trying to do.

Casteel: You did it! And then you got my dad running around trying to find a print because I was so obsessed.

Ringgold: A lot of artists don’t want to get involved with children’s books, because that’s not—

Casteel: —fine art?

Ringgold: Right. It’s not fine art. But I wanted to make one because I think children’s art lays the groundwork for adults to do it later. I loved it when my children were old enough to do some art. They used to do it on the wall, and I said, “Hey, wait a minute—don’t draw on the wall! Come on, you’ve got an easel here!” [Laughs.] But children are absolutely the best.

Casteel: Have you always considered yourself an educator?

Ringgold: Oh, absolutely. I taught all the way down and all the way up. I started out with the little ones, and I went on ahead and got my Ph.D. and all the licenses and everything. I taught elementary school, junior high, high school, and then on to college. I realized I wasn’t going to be able to stay anywhere too long, because they get tired of you and they want to keep somebody around who doesn’t make everybody else work so hard. I like to work! But I loved teaching and I loved what the kids do—kids are so creative. I just went along with it and it was great for me.

Jordan Casteel, Sylvia’s (Taniedra, Kendra, Bedelia, Crizette, De’Sean), 2018.

Courtesy Casey Kaplan, New York.

ARTnews: Harlem has figured prominently in both your lives. What rises to mind most immediately about the neighborhood’s significance to you?

Ringgold: All the important Black artists lived in Harlem. All you had to do was walk down the street and here they come. I was fascinated with them. But they didn’t want anybody to make a lot of fuss. I would say, “Oh my God, you’re Sam Gilliam!” or “You’re Aaron Douglas!” I got to know all those guys. Romy Bearden, all of them. And the jazz, the music—we had everything. People would come from all over the world to Harlem if they had a chance. And we had such great neighbors. I was fascinated by the stories they told. Everybody had stories, and I wanted to hear them. Today people don’t talk that much to each other.

Casteel: Not as much as they should. As a new person in Harlem—I consider it my transplanted, adopted home—I discovered the neighborhood as a Studio Museum in Harlem resident [in 2015–16]. And I immediately felt the energy that you’re describing, which I imagine was tenfold when you were there. Now, there are cars, headphones, cell phones—everyone’s looking down and focused on themselves. Everything is so self-centered these days. But I really wanted to get to know all the people I was walking by every day, so I would just walk up and say hello. It’s as simple as introducing yourself, and you build a whole network of family. Community builds by listening to one another. My parents taught me that, and their parents taught them that: as Black people growing up in New York, you go to the people across the street on the stoop. You say hello when you move to someplace new. They are the keepers of the stories of the neighborhood, and they are going to look after you.

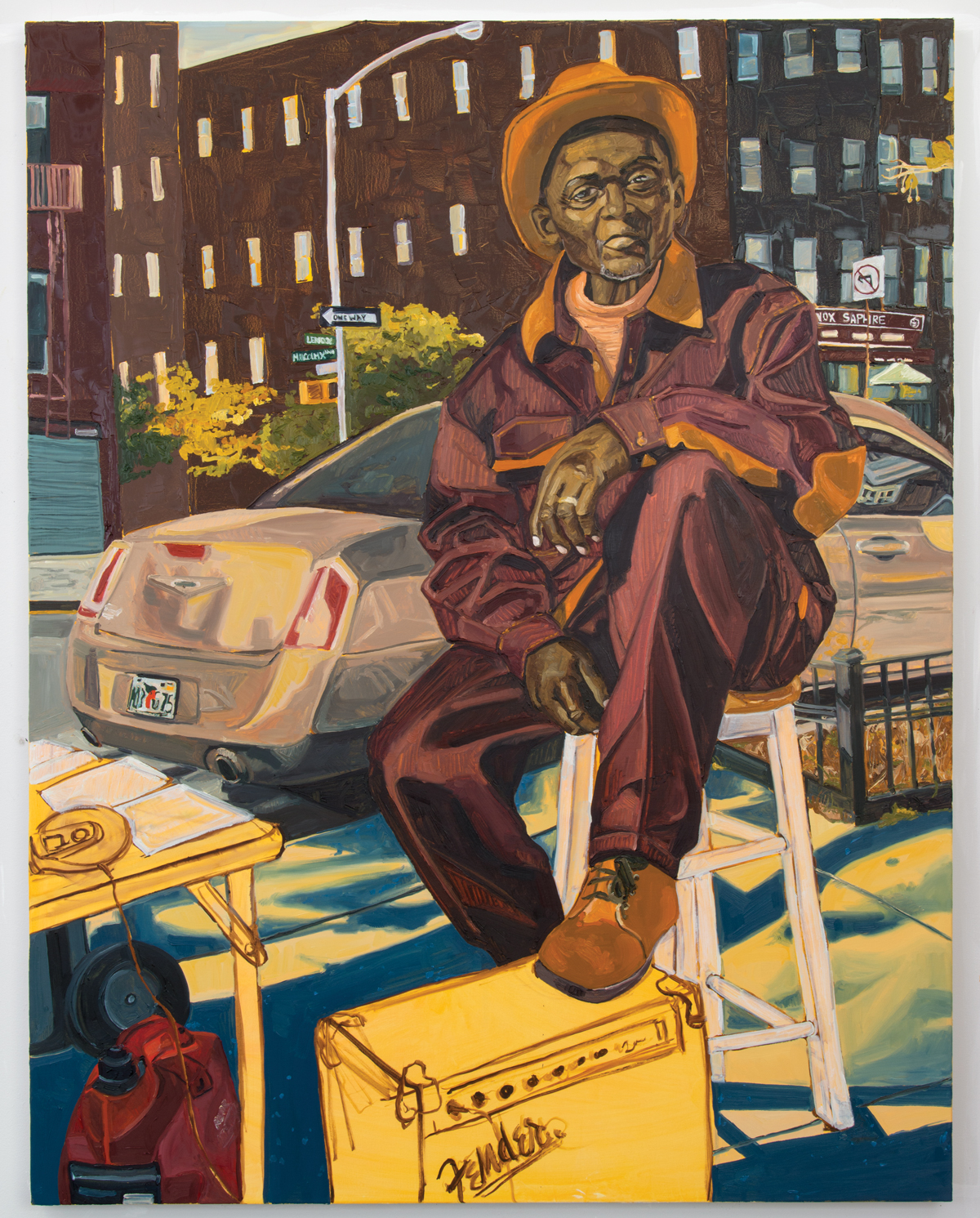

Jordan Casteel, James, 2015.

Courtesy Casey Kaplan, New York.

ARTnews: How has Harlem changed since you’ve been there?

Casteel: I’ve come into Harlem at a time when things are shifting quite rapidly. Lenox Lounge—people have told me stories about what that place represented, and it’s no longer there. Shake Shack has come in. One of the people I’ve painted—James, who’s become a dear friend of mine and is in his 80s—I asked him how he feels about the Starbucks that opened across the street from Sylvia’s. Things come and go, but people will always be here, telling stories. And it was important for me to acknowledge and hear those stories. For me, that really resonates. I knew I could call Harlem home before it was my home. There was a procession for my grandfather, Whitney Moore Young, Jr., when he passed that went down 125th Street. My blood and my ancestors set foot here long before I did and created a home for me before I even had to create a home for myself.

ARTnews: Through your grandfather and others, how did growing up with social-justice activism in your midst figure into the way you paint?

Casteel: There were certain values that were imposed on me. I grew up knowing that you are not one—you are a community. The sense of getting to know your environment and its stories is really important, and that came from my grandfather and his work. It went on to my mother, who has always worked in philanthropy and taught me a philanthropic social-justice way of moving through the world since the day I was born. That has always been consistent with who I am. I’m always thinking about relationships and the ways we are communicating with one another, making sure that all voices are heard within the space that I occupy.

When I started painting, I read a quote of yours, Faith, talking about the moment you said, “I’m not going to do landscape painting.” At some point you realize that if you’re going to do this, you’re going to do it and use your voice—as a catalyst to create change and paint the world you hope to see. That happened for me in graduate school, when I thought about how I could use my practice of painting to say something, even if it’s not as explicit as I think oftentimes people make it out to be. My existence as a Black woman making work at 31 in New York is political. I mean, there’s something about being a Black woman artist that inherently feels political. I have to acknowledge that and push back in ways that are an act of justice and create space for those who come behind me. I’m always thinking about my students [at Rutgers Univsersity] and what I want them to experience in the art world. I want to create a more equitable experience for them. Sometimes that comes with some blood, sweat, and tears—and difficult conversations. But without passion, it’s pointless, all of it.

Faith Ringgold, Groovin’ High, 1996.

ARTnews: Faith, how does it feel to hear younger artists like Jordan talk about the importance of your legacy? Do you recognize your own role in the present?

Ringgold: I know I did a lot to make things better for Black people, and women in particular. I’ve met a lot of young people like you today who have benefited as artists and continue to work. They don’t see what I saw, but it doesn’t matter. There’s a certain warmth in New York. It’s the kind of place where whatever it is you go there to do, you’re going to find a door open to let you in to do it. That’s what is so great about New York. You can always find an opening somewhere.

Casteel: But you created the space for people like me. I have an acute awareness that I couldn’t enter certain spaces [otherwise]. Like my show at the New Museum—it’s amazing that you were doing that long before I did. Knowing that you existed in that kind of space gives us permission as young people to feel empowered to create space for ourselves. I definitely feel that.

ARTnews: Faith, do you feel a connection to younger artists protesting inequity and injustice at institutions these days?

Ringgold: Well, there was nothing but protests when I was young in New York. We all did it. It’s a totally different kind of protest that we had back in the day. In fact, there used to be a protest march every weekend down Seventh Avenue in Harlem.

Casteel: That’s starting again—that kind of energy.

Ringgold: It’s different in some senses but I guess not all that much different. It’s what we’ve always done—pick up on something that’s happening, make a big deal of it, and correct it.

ARTnews: Are you hopeful for the prospects of results?

Ringgold: Do I have a sense of hope? I don’t know. At this stage in my life I can no longer sit back and hope. What is it really going to do for us? The pandemic is interfering with what the movement’s results will be. We’ve been through other sorts of epidemics or crises, but never anything like this. This is outrageous.

ARTnews: Jordan, what has been your experience of the Black Lives Matter protests of late?

Casteel: I think they’re profoundly important. The act of protest is always of the utmost importance—to use and utilize our voices by any means necessary. There has always been power in collectivity. What we’re seeing now—what kind of gives me hope—is that Black people are tired and, though communities of color have a lot of fight in us, to also see other people take the mantle on behalf of our lives is really empowering. I’m grateful for that. I hope it continues—other people’s sense of necessity and urgency that we have been feeling our entire lives. I just want the momentum to maintain. In general, I feel like the ground is shifting beneath us, and it’s going to create change that is necessary to better our future and systems that have been wrong for many years. It’s like everybody is forced to reckon with their own humanity right now, in every capacity.

Ringgold: Yes. It’s amazing. I can’t isolate myself, because then I won’t know what’s going on. I have to know what’s going on to get inspiration. I’ve got to stay in touch with the present and the people in it.

Soft sculptures on view in the exhibition “Faith Ringgold: The 70s,” 2018, at ACA Galleries, New York.

© 2020 Faith Ringgold/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy ACA Galleries, New York.

ARTnews: Will that inspiration figure into your artwork?

Ringgold: Well, I keep trying to look at it and see what I see, and I can’t place it just yet. It will come. But right now, I don’t know what’s going on. I know how I feel about it, but how to envision it, how to get a concept of it in my head—I don’t have it together. This is young people doing this—this is a young people’s thing.

ARTnews: Jordan, are you inspired artistically by what’s going on?

Casteel: I think there’s no way not to be in the sense that my practice is centered on the most authentic version of the world that I can find. That authenticity holds truth, and that truth holds pain, and that truth holds fear. I feel urgency. There’s a sense of urgency that is deeply affecting the way I’m moving through space and engaging with institutions. Every place around me is now a piece of the puzzle, and we have to hold each other accountable, for our systematic racist beliefs and also for wearing masks and thinking about other people. What’s interesting to me about this all happening at the same time is that it’s centered around coming outside of oneself and thinking about our effects on others. We put on our masks to protect others. We think about police reform to protect others who we might not even know. It’s the deepest act of empathy, and that does invigorate my practice. I feel inspired to work.

ARTnews: Faith, can you imagine trying to engage the protests in your art in some way?

Ringgold: I think I will. But I’m not ready yet. I don’t have a true sense of what is really going on that I can react to in some visual way. I can’t think of what I would like to record at this time. But something’s coming out of it, without a doubt.

ARTnews: Jordan, how might it affect your practice?

Casteel: Nothing happens without the work. I am in motion when I am making paintings, and the world’s in motion with me. If I am going to commit to painting Black and Brown bodies—and I will continue to do that—it is going to be an act that contributes to the conversations that are happening right now. I’ve been doing this work all along, and the people are just becoming more aware of it. That’s how I feel about how art history functions, too—thinking about what it means that people are becoming aware of Black art at this time and historicizing it and trying to make sense of the past and the present. For me, as a person of color, that’s all I knew. Charles White, Faith Ringgold, Romare Bearden—that was my history. It actually wasn’t until later in life that someone told me there was a “more important” history I needed to know.

There’s this part of me that always struggles with the sense that people are having an awakening around Black art, because we’ve always been here. We are plenty. We are thick as thieves. We are having these conversations all the time. We’re collecting our histories, and it’s exciting that people are paying attention. But I’ve been in fear for my Black body and space for as long as I’ve lived. And the same was true for my parents and grandparents and great grandparents.

That video of George Floyd is absolutely horrifying. There’s no question that it is horrifying—it’s a visceral experience when you see something like that on your couch, on your cell phone, and it changes people’s understanding. But I’ve been telling people for a long time that Black and Brown bodies are being killed and subjected to that kind of violence, and nobody believed it. It’s like how nobody believed we were great and now they’re like, “Black artists are great!” We’re like, “We know! Thanks for catching on!”

Installation view of “Jordan Casteel: Within Reach,” 2020, at New Museum, New York.

Photo: Dario Lasagni

Ringgold: Creativity is very empowering. You can’t always do something to make the time better, but you can go ahead and change it.

Casteel: To live and breathe as Black and Brown bodies, and to fight for what we believe in is an act in opposition to what we were brought to this country to do. And that’s a fight that I’m going to keep fighting as long as I can, in a way that my ancestral blood and my community have taught me to do.

Ringgold: It’s a way of life—to participate in your own culture. It’s always going to be positive. The thing that always upset me about the art world was that it was so difficult to get an opportunity to do it. You were subjected to a lot of racism.

Casteel: And that’s a part that still has to change. I hope it does change with people’s reckoning and understanding and desire for knowledge around Black art in the history of our communities. As people start to make space, it will be easier to enter those spaces and we won’t have to fight so hard. For some of us it’s been an internal joke—like, “It’s ‘Call-the-Black-Artist Week!’” But we’ve always been here, and we have a story to tell.

Ringgold: Yes, indeed. It’s an open door.

Casteel: And there’s a real shift in my experience compared to yours. The challenges that I face are less visible. I’m given the opportunity to have a show at an institution, but my voice is not always valued in that space. That comes from how young I am, it comes from being a woman, it comes from being a woman of color. There is a constant struggle, and I often feel that my voice is not really given a seat at the table. It’s like the difference between “diversity” and “inclusion.” You put me at the table, but you’re not going to let me speak. My generation is at the table, but we’re still trying to figure out how to speak and really be heard and included in the conversation. There’s still a gap there.

Ringgold: Yeah, and it has a lot to do with the way you see and how you can project what it is you’re feeling about what’s happening around you. You’ve got to have courage because, in the beginning, they may not like it so much. You’ve got to be out there. You’ve got to be fearless.

A version of this article appears in the Fall 2020 issue of ARTnews, under the title “Faith Ringgold & Jordan Casteel.”

Published at Tue, 15 Sep 2020 16:13:37 +0000