[ad_1]

Takis (left) and Guy Brett (right) photographed in 1966 by Clay Perry.

©CLAY PERRY AND ENGLAND & CO GALLERY, LONDON

Takis, who produced some of the strangest and most indelible examples of Kinetic art during the 1950s and ’60s, has died at 93. The news was announced on social media on Friday morning by his Athens-based foundation, which supports scientific research and houses the artist’s archives, and it comes just one month into the run of a Takis retrospective currently on view at Tate Modern in London.

“A prolific and visionary mind, whose ingenuity, passion and imagination was endless, Takis explored many artistic and scientific horizons, as well as music and theatre, and redefined the boundaries in art,” the foundation wrote in its announcement. “Thanks to his creative genius on so many levels, his generosity and his exceptional intuition, Takis was ahead of his time, which widely contributed to his success throughout the world. Today, we have all lost an extraordinary mind.”

In interviews, Takis frequently said his interest was energy—the hidden forces that guide life in our technological age. With the hope of showing how such forces function, he created bizarre assemblages of industrial materials, lights, and magnets. They inspire awe through low-tech means, causing elements to float inches of the ground or metal scraps to move as if on their own. At times, these works can resemble something less like artworks than science experiments—and Takis did not seem to mind if they were characterized that way. He even called himself an “instinctive scientist” sometimes, preferring the label to that of an artist.

Two examples of this sensibility were on view at Documenta 14 in Greece in 2017. One such work, Gong (1978), featured a long metal sheet suspended from the ceiling and a swaying electromagnet. Occasionally, the magnet would swing into the sheet, producing a loud clang as it did so—a hard-to-miss and entrancing gesture.

Takis, Magnetic Wall 9 (Red), 1961, Acrylic paint on canvas, magnets, copper wire, foam, paint, plastic, steel, synthetic cloth.

GEORGES MEGUERDITICHIAN/©2019 ADAGP, PARIS, AND DACS, LONDON/CENTRE POMPIDOU, PARIS

Scholars who have written about Takis’s work have described two breakthrough moments for the artist, who was born and raised in Greece, and later went on to work in various cities around Europe in the postwar years. In 1957, while traveling in London, Takis, who at that point was a sculptor of figural works that combined the aesthetics of modernism and Cycladic art, was at a train station when he found himself fascinated by the flashing lights and the locale’s overall aura. Two years later, while in the company of a budding avant-garde scene in Paris, he settled on what would become his work’s defining material: magnets.

“Using magnetism, light and sound as his raw materials, Takis’s audacious sculptures were a radical break from convention,” Achim Borchardt-Hume, the director of exhibitions and programs at Tate Modern, said in a statement. “I’m sure he will continue to be an inspiration to artists for generations to come.”

Though until the past few years Takis’s work had faded into obscurity, the artist was considered a sensation by the art worlds of Europe and America during the ’50s and ’60s. John and Dominique de Menil, two of America’s most prominent collectors at the time, were early supporters of Takis, and Alexandre Iolas, a key dealer in the New York art scene, showed his work.

Takis, Télélumière No. 4 (detail), 1963–64.

©2019 ADAGP, PARIS, AND DACS, LONDON/PHOTO: ©TATE/ANDREW DUNKLEY AND MARK HEATHCOTE/TATE

In 1963, Iolas’s gallery showed new works from one of Takis’s most famous series, the “Télémagnetiques”—a group of vividly colored paintings that, through metal wiring and magnets, cause objects to appear suspended midair just inches from their surface. (Takis said that the colors of the paintings, which ranged from eye-popping red to mustard yellow, were intended to channel pure energy.) “The sculptor’s intention is not to create a kind of Dadaist art, nor yet a Tinguely machine, but to demonstrate the esthetic possibilities of an actual magnetic force,” Lawrence Campbell wrote in a review for this magazine.

But these were hardly the strangest parts of Takis’s out-there oeuvre. In 1960, for Galerie Iris Clert, an epicenter of avant-garde activity in postwar Paris, Takis staged a performance in which he made the poet Sinclair Beiles, after reading a work in which he likened himself to a sculpture, float. Made just months before Yuri Gagarin became the first human to go to outer space, the work has been considered by some to be emblematic of the Space Age; it only exists now in photographic documentation shot by a very young Hans Haacke. And in 1968, working as a fellow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Center for Advanced Visual Studies in Cambridge, Takis continued pushing boundaries by levitating new objects—including, this time, liquids.

Takis’s desire for magnetic energy was a such a strong compulsion that, in works from the ’70s, he even lent his work an erotic touch. For a series called the “Sculptures Érotiques,” Takis created bronze works that resembled human bodies with objects floating around them. One based on an image of Saint Sebastian prominently features an erection.

Though Takis’s sculptures are best known for their formalist experimentation, the artist had a political streak as well. In 1969 Takis made the front page of the New York Times for a minor controversy that had far-reaching impacts. The Museum of Modern Art in New York was mounting an exhibition “The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age,” and included was a work by Takis that was given to MoMA by the de Menils. Takis said he wasn’t consulted about his inclusion in the show, however, so he, along with several of his artist colleagues, marched into the museum, took away the sculpture, placed it in the institution’s garden, sat around the work, and demanded to speak to the museum’s director. Eventually, MoMA conceded to Takis’s demands to remove the work.

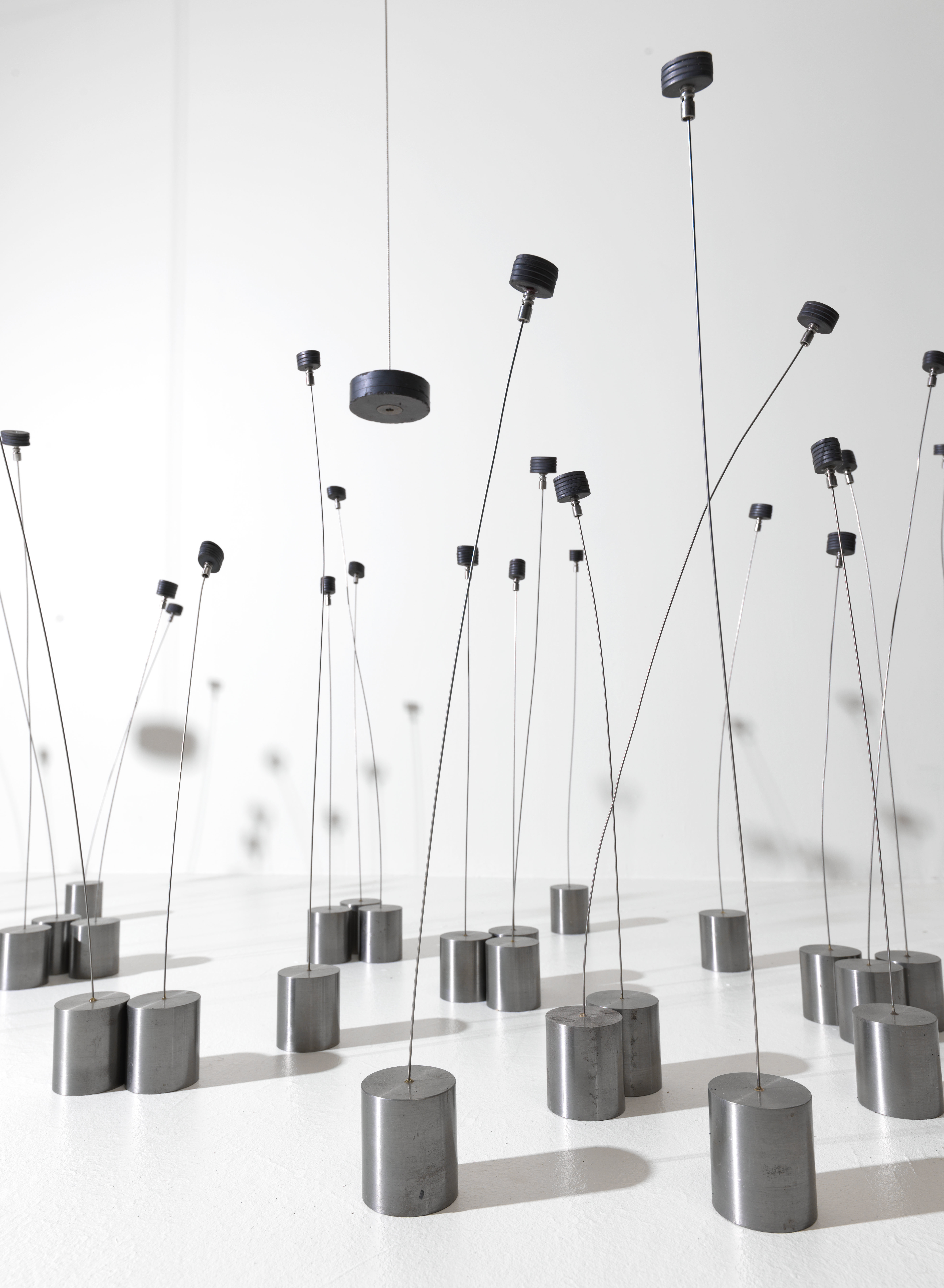

Takis, Magnetic Fields (detail), 1969, metal, magnets, wire.

PHOTO: GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM, NEW YORK/©2019 ADAGP, PARIS, AND DACS, LONDON

The work’s removal led to the formation of the Art Workers’ Coalition, a pioneering group of artists focused on the political implications of their work that, in its early days, included Takis, Haacke, sculptor Carl Andre, and critic John Perreault. That same year, they organized one of the most memorable events in recent art history—an art strike intended as a protest against the Vietnam War in which MoMA, the Whitney Museum, the Jewish Museum, and various New York galleries closed for the day.

The AWC may have been short-lived—it disbanded two years after its formation, in 1971—but its effects have been vast. In encouraging artists to control how their work was displayed and to take accountability for their work’s social and political contexts, Takis and the other members of the AWC have permanently left their mark on art history. It is difficult to imagine eight artists’ recent demands to remove their work from the Whitney Biennial amid controversy over a since-resigned board member without Takis’s 1969 action.

To some degree, Takis’s firebrand political spirit during the ’60s can be attributed to his upbringing. Takis was born as Panagiotis Vassilakis in 1925 in Athens. For much of his childhood, his country was either occupied or under the control of dictatorial regimes. Early on, he was a member of the United Panhellenic Organization of Youth, a group that led resistance actions against the occupation of his country by Axis nations during World War II. As part of his political endeavors at the time, he went to jail for six months.

Takis, Telepainting, 1959, Ceramic, iron, lamps, magnet, nylon thread, plastic, rheostats, steel screwdriver, vinyl, wood.

PHOTO: ©TATE (ANDREW DUNKLEY AND MARK HEATHCOTE)/ART: ©2019 ADAGP, PARIS, AND DACS, LONDON/PRIVATE COLLECTION

Because Takis’s family was poor and because his country was occupied, the resources for a formal artistic education were limited, but he was able to teach himself, mainly by reading up on science, mythology, and art, and by looking at modernist art. Once the war ended, he began making work under the sign of Pablo Picasso and Alberto Giacometti—both of whom radically transformed his practice.

In the recent years, Takis’s work has been shown widely. In 2015 Takis had his first major U.S. museum survey at the Menil Collection in Houston, Texas; that same year, the Palais de Tokyo in Paris also surveyed his art. A retrospective now on view at Tate Modern is set to travel to the Museu d’Art Contemporani di Barcelona later this year, and to the Museum of Cycladic Art after that. In addition to appearing in Documenta’s 2017 edition, he also appeared in the quinquennial’s 1964 and 1977 exhibitions.

Today, as artists are making use of much more expensive and refined digital technologies in their works, it can be hard to remember just how influential Takis’s lo-fi interventions have been. But, as artists continue to harness hardware, computers, and other digital materials for their physical, scientific, and sculptural properties, it’s obvious that Takis’s pioneering use of magnets, metals, and more—the stuff of his day’s new technologies—has had its influence. As Toby Kamps, the curator of Takis’s Menil Collection show, told Vice, “These are things like magnetism and gravity that hold us on the planet and in orbit around the sun, you know, the vast and powerful energies that shape reality, rather than the ‘oh gee wow’ screen-based consumer electronics world that we live in now.”

[ad_2]

Source link