[ad_1]

©2018 SUCCESSIÓ MIRÓ/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/ADAGP, PARIS

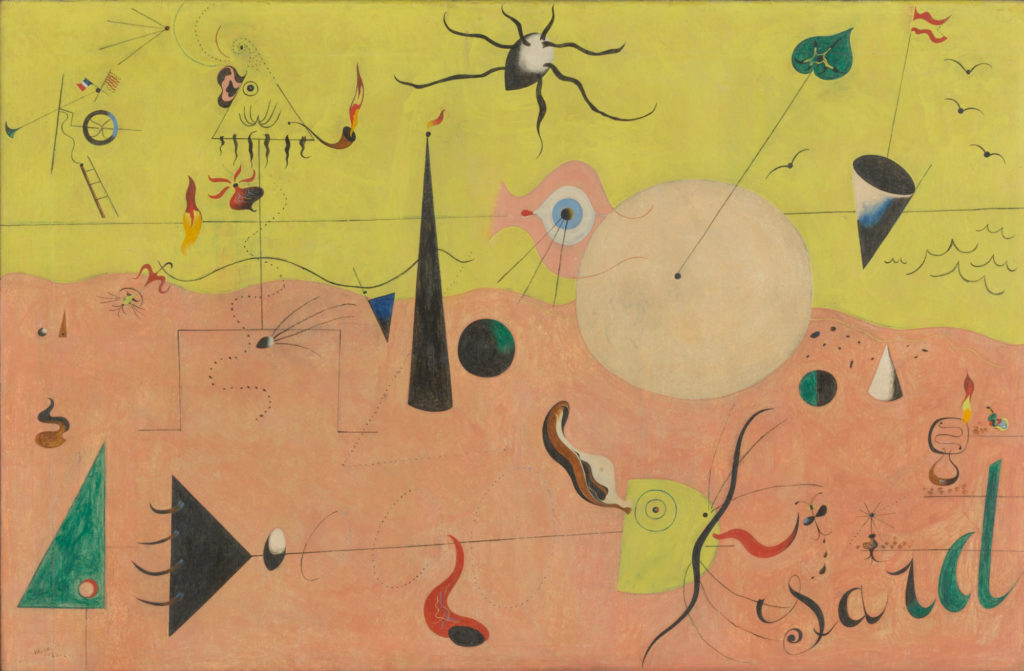

With an exhibition of Joan Miró’s work now on view at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, we turn back to the May 1959 issue of ARTnews, for which artist Robert Motherwell delved into the work of the Spanish painter on the occasion of another MoMA show. Motherwell enumerates the multitude of reasons why he loves Miró, both as a person and as an artist, noting the many ways he’s able to keep his canvases light and playful, and still meaningful all the same. “No wonder he loves Mozart,” Motherwell muses. Motherwell’s essay follows below. —Alex Greenberger

“The significance of Miró”

By Robert Motherwell

May 1959

An American abstractionist discusses Miró’s role in modern art and its evaluation, as shown in the Museum of Modern Art’s retrospective

I like everything about Miró—his clear-eyed face, his modesty, his ironically-edged reticence as a person, his constant hard work, his Mediterranean sensibility, and other qualities that manifest themselves in a continually growing body of work that, for me, is the most moving and beautiful now being made in Europe. A sensitive balance between nature and man’s works, almost lost in contemporary art, saturates Miró’s art, so that his work, so original that hardly anyone has any conception of how original, immediately strikes us to the depths. No major artist’s atavism flies across so many thousands of years (yet no artist is more modern): “My favorite schools of painting are as far back as possible—the primitives. To me the Renaissance does not have the same interest.” He is his own man, liking what he likes, indifferent to the rest. He is not in competition with past masters or contemporary reputations, does nothing to give his work an immortal air. His advice to young artists has been: “Work hard—and then say merde!” It never occurs to him to terrorize the personnel of the art-world, anxiety-ridden and insecure, as many of our contemporaries, angry and hurt, do. He believes that one’s salvation is one’s own responsibility, but with his own sense of right. One might say that originality is what originates just in one’s own being. He is a brave man, of dignity and modesty, passion and grace.

He has the advantage of liking his own origins. . . . But he worked in France during the ’twenties and ’thirties, mainly in the Surrealist milieu, to which he is greatly indebted, and of which he is, among other things, a leading exponent. With the outbreak of the war in 1939, Miró as a neutral returned to the relative artistic isolation of his native Catalonia, a part of Spain that is energetic, hard-headed, republican and straight, involved in neither mysticism nor blood-ritual. He lives in a magnificent studio-house in Palma, designed for him by José Luis Sert, now of Harvard, who designed the Spanish Pavilion at the Paris World Fair in 1937 that was decorated by Miró and by Picasso’s Guernica. There was a time in the ’twenties when Miró was so poor that he gave André Masson a lunch of radishes and butter and bread; it was then that he wrote a lovely piece called I Dream of a Big Studio. Palma is the native island of his wife, to whom he is deeply devoted. “Painting or poetry is made as we make love, a total embrace, prudence thrown to the wind, nothing held back. . . .” He is sixty-six the same age as Most General Franco. I hope that Miró lives to be a hundred, in good health.

In the past two decades, Miró has increasingly devoted himself to crafts, to the world of the artisan. His collaboration with the Spanish ceramicist Artigas is well known, as are his lithographs, engravings, book-illustrations and woodcuts, printed in teamwork with master artisans in Paris. He has spoken eloquently about all this recently: “I do not dream of a paradise, but I have a profound conviction of a society better than that in which we live at this moment, and of which we are still prisoners. I have faith in a future collective culture, vast as the seas and the lands of our globe, where the sensibility of the individual will be enlarged. Studios will be re-created like those of the Middle Ages, and the students will participate fully, each bringing his own contribution. For my part, my desire always has been to work in a team, fraternally. In America, the artisan has been killed. In Europe, we must save him. I believe that he is going to revive, with force and beauty. These past years have seen, nevertheless, a re-evaluation of the artisan’s means of expression: ceramics, lithos, etchings. . . . All these objects, less dear than a picture and often as authentic in their plastic affirmation, will get around more and more. The supply can equal the demand, understanding and growth will not be restricted to the few, but for all.” We feel the melancholy shadow of Franco’s gloomy, suppressed Spain over his words, as well as the human desire to escape one’s solitary studio that nearly every modern painter feels on occasion. But Miró must also feel, with his incredible sensitivity to the various materials of plastic art, like his peers Matisse and Picasso before him, continual inspiration in sensing out a new material, and in finding that precise image that stands at an equal point between its own nature and his own. And who would not prefer the constant company of artisans to that international café society around art that otherwise surrounds us? When he was in America twelve years ago, making a beautiful mural for a hotel in Ohio, he answered questions about how he likes to live: “Well, here in New York I cannot live the life I want to. There are too many appointments, too many people to see, and with so much going on I become too tired to paint. But when I am leading the life I like to in Paris, and even more in Spain, my daily schedule is very severe and strict and simple. At 6 A.M. I get up and have my breakfast—a few pieces of bread and some coffee—and by seven I am at work . . . until noon. . . . Then lunch. . . . By 3 I am at work again and paint without interruption until 8. . . . Merde! I absolutely detest openings and nearly all parties. They are commercial, ‘political,’ and everyone talks so much. They give me the ‘willies.’ . . . The sports! I have a passion for baseball. Especially the night games. I go to them as often as I can. Equally with baseball, I am mad about hockey—ice hockey. I went to all the games I could . . .”

Critics rarely talk about the subject-matter, save for the fact that he loves the landscape of his native Catalonia. All the shores of the Mediterranean drenched in intense, saturated color, and inhabited by various folk whose habits go back to the beginnings of recorded and painted history. From this environment come Miró’s instinctively lovely colors, the bright colors of folk art—reds, ultramarine blues and cobalt, lemon yellow, purple, the burnt earth colors, sand and black. His colors are born for white-washed plaster walls in bright sunlight. These colors are as natural to his region as to the whole Mediterranean basin, and from there beyond to the Near East, India, China, Japan, Mexico and South America, wherever a folk still exists in the sun. But his color-structure rarely becomes a major, or a profound weapon of getting at you, as it does in Matisse, in the old Bonnard, in Rothko. Instead it is simply universally beautiful, as long as there is a sunlit folk, with “primitive” feelings.

His main two subjects are sexuality and metamorphosis, this last having to do with identity in differences, differences in identity, to which he is especially sensitive, like any great poet. As Picasso says, painting is a kind of rhyming. Miró is filled with sexuality, warm, abandoned, clean-cut, beautiful and above all else intense—his pictures breathe eroticism, but with the freedom and grace of the India love-manuals. His greatness as a man lies in true sexual liberation and true heterosexuality; he has no guilt, no shame, no fear of sex; nothing sexual is repressed or described circumspectly—penises are as big as clubs, or as small as peanuts, teeth are hack-saw blades, fangs, bones, milk, breasts are round and big, small and pear-shaped, absent, double, quadrupled, mountainous and lavish, hanging or flying, full or empty, vaginas exist in every size and shape in profusion, and hair!—hair is everywhere, pubic hair, underarm hair, hair on nipples, hair around the mouth, hair on the head, on the chin, in the ears, hair made of hairs that are separate, each hair waving in the wind as sensitive to touch as an insect’s antenna, hairs in every hollow that grows them, hairs wanting to be caressed, erect with kisses, dancing with ecstasy. They have a life of their own, like that Divine hair God left behind in the vomit of the whore-house Lautréamont. Miró’s torsos are mainly simplified shapes, covered with openings and protuberances—no creatures ever had so many openings to get into, or so many organs with which to do it. It is a coupling art, an art of couples, watched over by sundry suns, moons, stars, skies, seas and terrains, constantly varied and displaced, like the backgrounds in Herriman’s old cartoons of Krazy Kat. But in Miró there are no dialogues. Simply the primeval energy of a universe in which everything is attracted to everything else, as visibly as lovers are, even if they are going to bite each other. In Picasso the erotic is actually idyllic, more rarely rape, and now lately old men looking in lascivious detachment at young nudes. In Miró there is constant interplay. Even his solitary figures are magnetized, tugged at by the background, spellbound by being bodies on the move. It is a universe animated by the pull of feeling.

©2018 SUCCESSIÓ MIRÓ/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/ADAGP, PARIS

How Miró makes a painting is interesting. As Renaissance painters did, he proceeds by separate steps (though his process has nothing else in common with Renaissance painting, any more than does his image of reality). The whole process is pervaded throughout by an exquisite “purity,” that is, by a concrete and sensitive love for his medium that never distorts the essential nature of the medium, but respects its every nuance of being, as one respects someone one loves. The nature of the medium can be distorted by a brutal or insensitive artist, just as a person’s nature can be distorted by another human being. The painting medium is essentially a rhythmically animated, colored surface-plane that is invariably expressive, mainly of feelings—or their absence. . . . The expression is mainly the result of emphasis, is constituted by what is emphasized, and, more indirectly, by what is simply assumed or ignored. In “bad” painting, the emphases are essentially meaningless, i.e., not really felt, but counterfeited or aped. . . . There are not many painters as sensitive to the ground of the pictures at the beginning of the painting-process as Miró—Klee, the Cubist collage, Cézanne watercolors, Rothko come to mind, and the Orient, with which he otherwise has no affinity. When Miró has made a beautiful, suggestive ground for himself, intentionally the picture is half-done (technically a third-done), whether he chooses a beautiful piece of paper (sand or rag) and just leaves it as the ground, or whether he scrubs it with color, color-patches, or a single color all-over, or color-patches and a main color both. Indeed, there is a picture at the present exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art that is simply a blue-brushed color plane, punctured in the upper left corner by a hole the roundness of a pencil, and in the lower right corner his tiny signature and the year. The picture stands. Brancusi polished his statues with the same love. Matisse did it the other way round. He made his revisions on working canvases, and then made the final version as clean and pure as Miró’s paintings, but with an infinitely more subtle and varied brush—but then Matisse’s brush is the most subtle since Cézanne’s, the most complicated and invariably right in its specific series of emphases. What a miracle it is! It’s as though the brush could feel, breathe and sweat and touch and move about, as though sheer being contacted sheer being and fused. After the artist who did it is dead and gone, we can still see that intense moment captured on the canvas. That is the miracle for the audience. Miró’s miracle is not in his brushing, but in that his surface does not end up heavy and material, like cement or tar or mayonnaise, but airy, light, clean, radiant, like the Mediterranean itself. There is art for his creatures to breathe and move about him. No wonder he loves Mozart.

To speak of Miró’s second step is to be forced to introduce two words that are perhaps the most misunderstood critical terms in America, “Surrealist automatism.” Miró’s method is profoundly and essentially Surrealist, and not to understand this is to misunderstand what he is doing, and how he came upon it, and usually derives from a mistaken image of Surrealism itself—which was a movement of ideas, had its greatest expression in all of literature, in French, and which produced the greatest painters and sculptors of the post-Picasso generation in Europe—Jean Arp, Max Ernst, Alberto Giacometti and Joan Miró, as well as a masterpiece of art-literature, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí. Painting is a secondary line in Surrealism and the dream images of Dalí-Tanguy-Magritte-Delvaux, on which the popular image is based, are a secondary line of its painting, which appears in a major way in the early de Chirico. Surrealist ideas pervade some of the most alive literature in Europe today. I for my part, though this is not my subject, believe that Surrealism is the mother, as certain philosophers are the father, of a major part of the attitudes in contemporary Existentialist literature and art. I believe, too, that the fact of the Parisian Surrealists being here in New York in the early ’forties had a deep effect on the rise of what is now called Abstract-Expressionism; for example, Surrealist automatism was discussed often with Jackson Pollock in the winter of 1941–42, before his first show; he made Surrealist automatic poems in collaboration with others that same winter—which is to take nothing from his personal force and genius. All this is a long and complicated story: but one can’t help remarking how fantastic are the lies that have been built up about those days during the last nineteen years, by people who were not around then, and even worse, by some who were—in the interests of chauvinism, of originality, of being first, of, as Harold Rosenberg quotes, everyone wanting to get into the act, an act that started so simply and straight.

Miró is not merely a great artist in his own right; he is a direct link and forerunner in his automatism with the most vital painting of today. The resistance to the word “automatism” seems to come from interpreting its meaning as “unconscious,” in the sense of being stone-drunk or asleep, not knowing what one is doing. The truth is that the unconscious is inaccessible to the will by definition; that which is reached is the fluid and free “fringes of the mind” called the “pre-conscious,” and consciousness constantly intervenes in the process. What is essential is not that there need not be consciousness, but that there be “no moral or esthetic a priori” prejudices, (to quote André Breton’s official definition of Surrealism) for obvious reasons for anyone who wants to dive into the depths of being. There are countless methods of automatism possible in literature and art—which are all generically forms of free-association: James Joyce is a master of automatism—but the plastic version that dominates Miró’s art (as it did Klee’s, Masson’s in his best moment, Pollock’s and many of ours now, even if the original automatic lines are hidden under broad color areas) is most easily and immediately recognized by calling the method “doodling,” if one understands at once that “doodling” in the hands of a Miró has no more to do with just anyone doodling on a telephone-pad than the “representations” of a Dürer or a Leonardo have to do with the “representations” in a Sears catalogue.

When Miró has a satisfactory ground, he “doodles” on it with his incomparable grace and sureness, and then the picture finds its own identity and meaning in the actual act of being made, which I think is what Harold Rosenberg meant by “Action-Painting.” Once the labyrinth of “doodling” is made, one suppresses what one doesn’t want, adds and interprets as one likes, and “finishes” the picture according to one’s esthetic and ethic—Klee, Miró, Pollock and Tanguy, for example, all drew by “doodling,” but it is difficult to name four artists more different in final weight and effect.

© 2018 SUCCESSIÓ MIRÓ/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/ADAGP, PARIS

The third, last stage of interpretation and self-judgment is conscious. A dozen years ago Miró explained to to J.J. Sweeney: “What is most interesting to me today is the material I am working with. It supplies the shock which suggests the form just as the cracks in the wall suggested shapes to Leonardo. For this reason I always work on several canvases at once. I start a canvas without a thought of what it may become. I put it aside after the first fire has abated. I may not look at it again for months. Then I take it out and work at it coldly like an artisan, guided strictly by rules of composition after the first shock of suggestion has cooled . . . first the suggestion, usually from the material; second, the conscious organization of these forms; and third, the compositional enrichment.” But it depends on the man. Dufy also went through three equivalent stages in his working process.

Lately Miró’s art has become more brutal, blacker, torn, heavier in substance, as though he had moved from the earlier comedies through Anthony and Cleopatra and Falstaff to King Lear, harsher, colder, ironic, more ultimate. There is one joke of God’s that no one can escape consciousness of—death.

In view of Miró’s greatness, the Museum of Modern Art is to be complimented on giving him his second retrospective there [to May 10], the largest show that he has ever been given. To my taste, there are too many apprentice works of before 1923–24, the winter in which he “found” himself, though, of course, museums are more interested in history than artists are; too many works that are familiar (about 100 of 116 works listed belong to American collections), though perhaps this is a practical necessity; and not nearly enough recent works. Still, it is a beautiful exhibition. The museum is going to publish a short illustrated monograph on Miró by James Thrall Soby; I hope someday he will give Miró the full treatment, as he did to de Chirico.

The Matisse Gallery had an exhibition called “Constellations,” after the title of the de-luxe volume of reproductions of twenty-two of Miró’s gouaches of nearly twenty years ago that they are publishing, surely the most beautiful and astonishingly accurate (many of the originals from which the reproductions were made were shown side-by-side in the gallery) book of color reproductions published in this country. Miró has described the making of the gouaches: “They were based on reflections in the water. Not naturalistically—or objectively—to be sure. But forms suggested by such reflections. In them my main aim was to achieve a compositional balance. It was very long and extremely arduous work. I would set out with no preconceived idea. A few forms suggested here would call for other forms . . .”

The Matisse Gallery was also going to show a book called Atmosphere Miró, published by Wittenborn, of photographs of Miró’s residences in Montroing and Barcelona and the surrounding vistas, but the book is not ready for release. Unaccountably, nowhere in the book is it made clear that Miró now lives in Palma, so that the book documents where Miró lived before, rather than his present atmosphere. But all of this contributes to the clarity of his image, an image that I for one shall not forget because of its beauty and courage and modesty.

[ad_2]

Source link