[ad_1]

By Hannah S. Ostroff

An evacuation exercise in Puerto Rico, held during training by the Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative (Photo by Yuisa Rios, FEMA)

When a natural disaster strikes, it devastates lives and homes, and can even destroy a culture’s identity and history.

After a disaster, humanitarian response is the top priority. But there is also a critical period to salvage and save damaged cultural heritage items. With proper training, people can act quickly to stabilize an important cultural resource, saving and preserving it for future generations.

Puerto Rico and other Caribbean islands experienced catastrophic damage when Hurricane Maria hit in the fall of 2017. As they rebuild, a team from the Smithsonian is working with local citizens to save and protect their cultural heritage for the future.

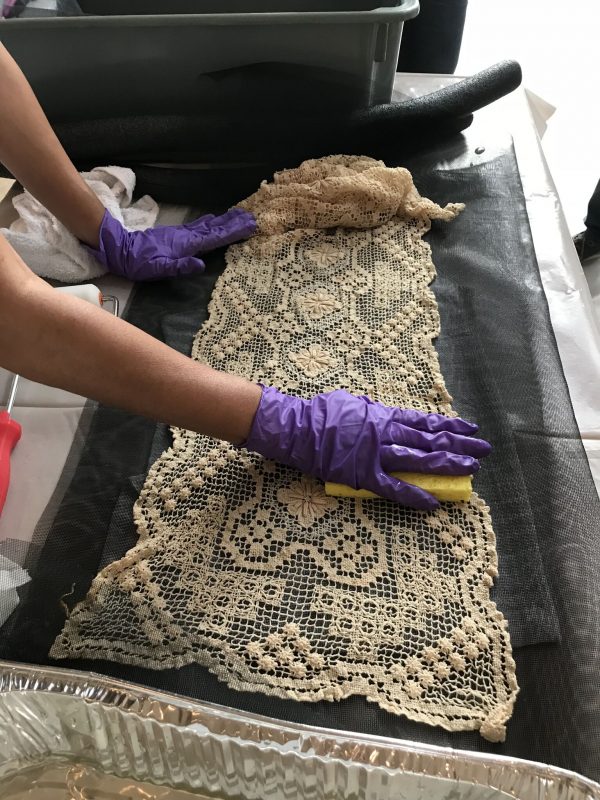

A former participant of the inaugural Heritage Emergency and Response Training from Puerto Rico demonstrates to the new Puerto Rican trainees how to gently dab moisture out of a fragile textile using a standard kitchen sponge.

The Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative works to protect and preserve cultural heritage in the U.S. and abroad, whether it’s threatened by natural disasters or human violence. The broad scope includes preserving objects and architecture—the main focus of the team’s work—and also includes saving less tangible cultural elements such as music and oral histories that speak to a shared past.

Smithsonian projects have included cultural rescue work in Haiti, Syria and Iraq, as well as disaster training for heritage colleagues, first responders and military personnel around the world.

In March, the Smithsonian Cultural Rescue Initiative team hosted training in Puerto Rico that focused on preparedness, response and recovery of domestic cultural heritage items in times of crisis. Participants spent time inside and outside the classroom, with opportunities to test their new skills during hands-on practical exercises in emergency action.

A demo “Mona Lisa” on the move after being documented and labeled a participant moves the piece to the packing area before transport to a safe storage space

The participants created a fake “State Museum of Smithsonia” where they could test their knowledge and skills. No collections objects were harmed in the training—that’s not a real Mona Lisa.

A hypothetical tropical cyclone hit the museum, and participants stepped up to evaluate the situation, and to document, pack, and eventually evacuate the collection.

A participant of the Heritage Emergency and Response Training analyzes a waterlogged photograph before beginning to salvage it

In emergency planning, it’s critical to think about what resources will be easily accessible, and how to use what you have. For example, the participants applied their training on handling damaged objects soaked with water by dabbing moisture out of a fragile textile with a standard kitchen sponge. They also analyzed waterlogged photos and paintings, and peeled soaked paper-based mounting from an artwork with gloved hands.

Participants discuss the space where the fictitious collection currently is in terms of how to grid the room. Gridding is an important step in the documentation process, which needs to be done before safely evacuating the objects. The arrow is pointing to hazard in the room, which is a broken window. (Photo by Yuisa Rios, FEMA)

Working in stations, the group learned proper handling procedures for many different collection materials: books, objects, paintings, textiles and photographs. The next day, they documented the fictitious collection before moving it to a safer location to protect against the chance of future damage.

Cultural heritage is not a renewable commodity. If it is gone, communities can lose not only resources for economic development, tourism and commerce but also inspiration, creativity and a sense of community.

[ad_2]

Source link