[ad_1]

The wholesale transition from analog to digital media at the turn of the twentieth century hit the Polaroid company particularly hard, although even after a series of bankruptcies and clumsy corporate restructurings diminished the company, Polaroid remains iconic. Its enduring relevance is reflected in the rise of Instagram, whose very name evokes the immediate development of instant film that is synonymous with Polaroid. The social media platform borrows shamelessly from Polaroid’s aesthetic: the square format, the bottom section reserved for text, the digital filters that suggest chemical coloration. Instagram repackages a colorful and beloved image culture from a bygone era.1 The digital afterlife of Polaroid makes its history timely and suited for reassessment.

Two exhibitions in the Boston area, where Polaroid was founded in 1937, capture this history. “The Polaroid Project: At the Intersection of Art and Technology” was scheduled to run through June 21 at the MIT Museum in Cambridge, and “Elsa Dorfman: Me and My Camera” was set to be on view across the Charles River at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, through the same date. Whereas the former is a survey of more than two hundred photographs by 120 artists, alongside more than a hundred examples of equipment and other material artifacts, the latter is a focused retrospective of self-portraits by a venerated Cambridge-based artist, best known for her large-format Polaroid photographs.

© Lucas Samaras. Courtesy Pace Gallery.

After stops in Fort Worth, Vienna, Hamburg, Berlin, Singapore, and Montreal, “The Polaroid Project” finally made its way to Polaroid’s hometown. The show’s five-person curatorial team comprises staff from the Foundation for the Exhibition of Photography in Minneapolis, the Fotomuseum WestLicht in Vienna, and the MIT Museum; most of the photographs and objects on display belong to the permanent collections of WestLicht and MIT. Unlike reproducible prints made from a negative, each Polaroid image is unique. Because Polaroids are also more sensitive than regular prints to light and other environmental conditions, the curators produced two versions of the show, the second of which opened on March 7. By swapping some examples out for others, the curators showcase a larger number of photographs without tampering with the exhibition’s overarching framework.

© Barbara Crane

A giant rainbow is pasted across the floors and vitrines of “The Polaroid Project”—an obvious reference to the company’s longtime logo. The field of colors theatrically traverses the entire show, conjuring the impression of a particle of light bouncing back and forth through a camera. As its bold design indicates, this exhibition is a feel-good, heavily nostalgic celebration of Polaroid—as a technology, as an aesthetic, and, yes, as a multinational corporation. In 1932 Edwin Land (1909–1991) and George Wheelwright III (1903–2001) launched Land-Wheelwright Laboratories to research and fabricate synthetic light-polarizing materials that held tremendous possibilities for reducing glare in sunglasses, automobile headlamps, photographic filters, and other devices. Within five years the company renamed itself Polaroid, and Land took over. The loosely chronological exhibition begins with Polaroid’s development of instant photography in the late 1940s and extends through 2016. Throughout, the curators stress the entanglement of art and technology as being fundamental to “creativity.” This art-technology nexus is the main point of most curatorial and programming efforts at the MIT Museum, and the crossover is almost always framed as inherently positive.

© Chuck Close in association with 20×24 Studio, New York. Courtesy Pace Gallery.

The curatorial narrative is structured around numerous nebulous buzzwords printed on the walls, among them “innovation,” “impression,” and “instant.” However, the history of Polaroid is best grasped through the evolving design of the company’s devices and marketing materials, displayed in vitrines. Over the decades, the mass-produced cameras became smaller and sleeker; in the exhibition, they are interspersed with images made by fine-art photographers. Highlights include those by Joyce Neimanas, Lucas Samaras, Barbara Crane, and Sandro Oramas, many of whom had close relationships with the company. So did artists who aren’t usually considered photographers: Chuck Close, Marina Abramović, Charles Eames, and David Hockney. Starting with Ansel Adams in the late 1940s, Polaroid doled out cameras and film to photographers in exchange for critical feedback, as well as the resulting artworks. This Artist Support Program, which lasted until 2008, enabled the company to amass an impressive collection. The memorable images it holds range from Dawoud Bey’s Josef (1994), a large, arresting color portrait of a young man comprising four photographs hung in a grid, to Philip-Lorca diCorcia’s clusters of small, subtle, undated snapshots of urban space. Given these visual gems, it’s somewhat surprising that the curators made little effort to narrate aesthetic developments, tendencies, and divergences—or even propose a basic historical narrative for the works.

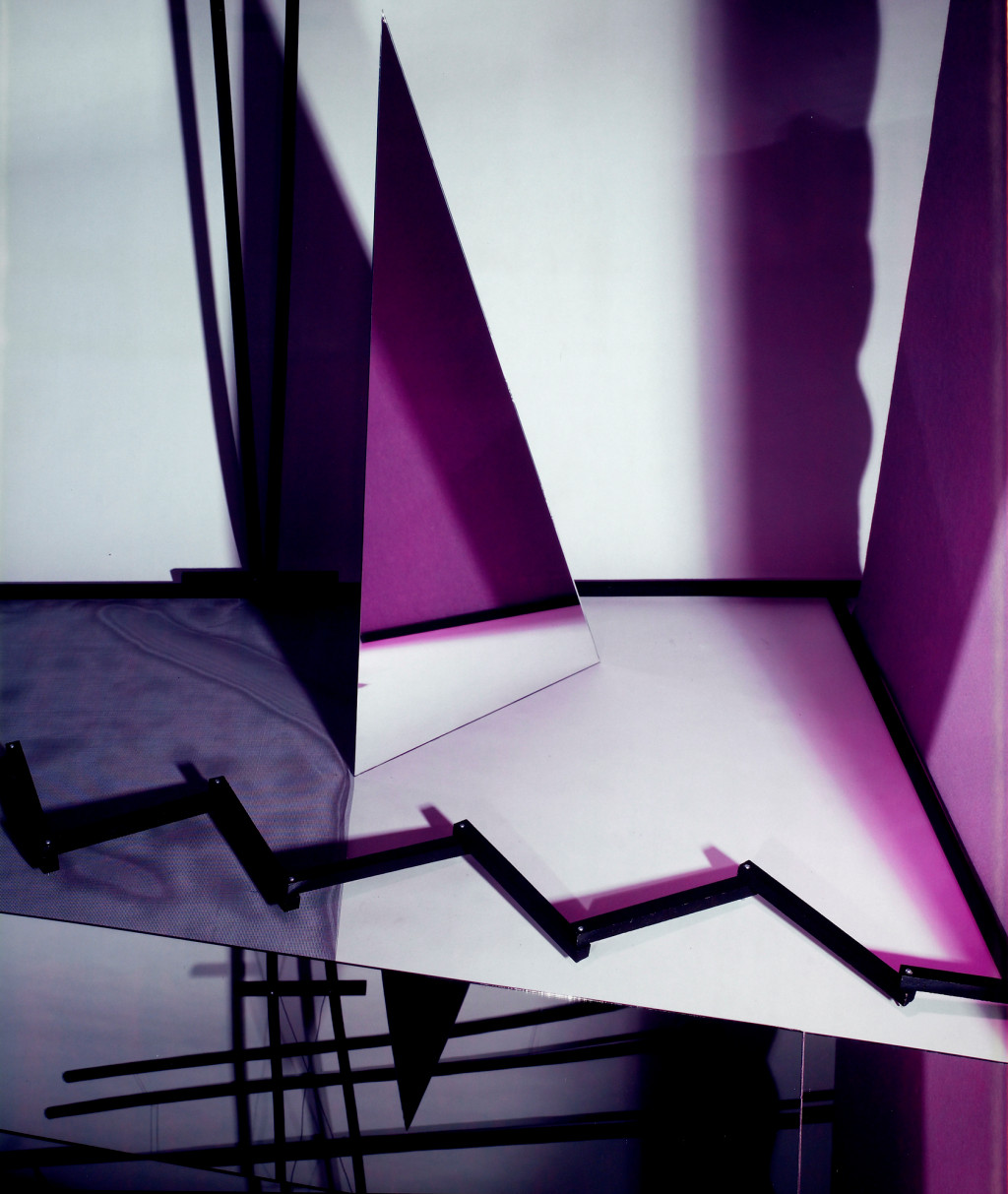

There is an odd disconnect between the images on the wall and the cameras in the cases. Not simply anyone can take a picture such as Barbara Kasten’s abstract masterpiece Construct PC/2-A (1981). Produced using a rare 20-by-24 large-format Polaroid camera (one of which stands in the gallery), this image captures the kaleidoscopic interactions between geometric sculptures and mirrors. The Polaroid products on display were generally made for mass consumption, and they gave birth to an influential vernacular aesthetic that touched many realms of cultural experience, from family life to nightlife. Yet these everyday snapshots are not on view: the walls belong to a sophisticated and professional genealogy of fine-art photography, which represents a mere sliver of the history of Polaroid. This genealogy, the curators mistakenly imply, rarely intersects with histories of amateur and quotidian photography. The exhibition would have benefited from examining vernacular works by nonprofessionals alongside those taken as part of the Artist Support Program in order to show discrepancies and interplays between these echelons of expression and expertise.

Also absent from “The Polaroid Project” is any serious consideration of the relationship between photography and power. Polaroid was a major global corporation, and its operations extended across the world in the Cold War era. For example, in the 1970s, various South African companies contracted Polaroid to provide cameras and film for identification cards and passbooks that black populations were forced to carry under the apartheid regime. After Boston-based black activists and Polaroid employees Caroline Hunter and Ken Williams discovered this, they founded the Polaroid Revolutionary Workers’ Movement in 1970, which led to the withdrawal of the corporation from South Africa in 1977. This local grassroots boycott and divestment campaign was instrumental in accelerating the global fight against apartheid.2 Questions of politics are explored in greater depth in the exhibition’s handsome catalogue, but it is troubling that “The Polaroid Project” shies away from being critical of its subject. This stance isn’t terribly surprising, however, given that one of the exhibition’s five curators, Barbara Hitchcock, was the director of cultural affairs for Polaroid, and the company’s media spokesperson.

Before the exit, there is an enormous touch screen on which the curators mention, at long last, that the first instant-film trial took place five hundred feet from the gallery, in 1943. Visitors can click on a few enlarged photographs by local artists for close-up viewing. Just as Polaroid penetrated postwar global visual culture, the Polaroid Corporation had a towering presence in the political, economic, and artistic landscape of Greater Boston. Every longtime resident has some sort of personal story about or connection to the company. Even though “The Polaroid Project” was a traveling exhibition, it missed the opportunity to address the crucial local dimensions of the company in any detail.

© Elsa Dorfman. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

HUMBLER IN SCOPE and ambition, Dorfman’s retrospective at the MFA Boston provides a welcome contrast to the sanitized survey, localizing and personalizing the history of Polaroid. Organized by curators Anne E. Havinga and James Leighton, the show focuses on the photographer’s unforgettable self-portraits that evolved in tandem with the history of Polaroid. Dorfman, whose two portraits of poet Allen Ginsberg from the early 1980s are also included in “The Polaroid Project,” began using one of the company’s large-format, 235-pound, 20-by-24 cameras in 1980. Polaroid produced only six of these hulking devices: they were enormous, difficult to move, and technically complex. Immediately enamored of the detailed, richly colored quality of the images it yielded, the photographer campaigned vigorously, and eventually convinced Polaroid to rent her one of the six on a long-term basis in 1987, an agreement that lasted until she announced her retirement in 2016.

In Me and My Camera (1986)—a work that inspired the exhibition’s title—the photographer cheerfully poses alongside her treasured machine, as if it were a family member, possibly with a degree of irony. Dorfman has used this camera to produce more than four thousand studio portraits of friends, family, clients, and herself, often to mark special occasions. Taken in her studio between 1980 and 2007, the compendium of fourteen Polaroid self-portraits on display at the MFA (most of which the artist recently donated to the museum) is a tribute to the changing times and to her lively cultural milieu.

Dorfman’s work blends the candid intimacies of the personal and the vernacular with the careful eye of a professional photographer. Back in the late 1960s and early ’70s—before her segue into Polaroid—Dorfman used a small-format camera and black-and-white film to represent her vibrant social world. Her images capture close friends, such as the poet Gail Mazur, and Dorfman’s husband, the attorney and journalist Harvey Silverglate, as they drink coffee, smoke, and talk on the phone. This community comes to life in Elsa’s Housebook: A Woman’s Photojournal (1974), a book of tender portraits illustrating a personal narrative that conversed with the enveloping currents of women’s liberation. This experimental book, accompanied by a few of the domestic portraits it features, was on display in a vitrine. Dorfman also turns the camera on herself. The book’s title page bears the image Me in My New Coat (1968) in which the artist photographs herself in a slender full-length mirror, her face obscured by her camera. The self-portrait feels awfully contemporary more than half a century later.

© Elsa Dorfman. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Connecting her portraits and her self-portraits, the artist has remarked, “Being comfortable with the camera on myself affected how I felt making pictures of other people.”3 Beyond comfort, her works radiate a contagious joy. In Me, with Peter and Allen During Their Photo Session. Isaac’s Amaryllis in Bloom From Studio Light (1980), Ginsberg, with a coy smile, intimately links arms with his partner, Peter Orlovsky, and an elated Dorfman, the shutter-release cable in her hand above a blossoming plant. Instead of trying to depict the psyche of her subjects or herself, Dorfman is playfully preoccupied with the act of posing. With its instantaneous materialization, the Polaroid image is perfectly suited for this kind of inquiry into candid moments.

As the exhibitions at the MIT Museum and the MFA together demonstrate, Polaroid engineered an irresistible aesthetic that continues to dominate the way we imagine, experience, and comprehend the world. In tackling an undeniably unwieldy subject matter, however, “The Polaroid Project” fails to elucidate a complex narrative about Polaroid’s manifold interventions in public and private cultures, on local and global scales. Meanwhile, Dorfman’s retrospective, with its distinct mingling of the personal, the vernacular, and the professional, reminds us of the various pleasures to be taken in photography. Unlike a Polaroid or Instagram image that reveals itself at once, the representation of history is not an instantaneous endeavor, but an ongoing pursuit. In the case of Polaroid, it looks like we may need to wait longer for multicolored critical and cultural histories to develop more fully.

1 For a helpful elaboration on the relationship between Polaroid and Instagram, see Alicia Chester, “The Outmoded Instant: From Instagram to Polaroid,” Afterimage 45, no. 5, 2018, pp. 10–15.

2 For more on this history, see Eric J. Morgan, “The World Is Watching: Polaroid and South Africa,” Enterprise & Society 7, no. 3, 2006, pp. 520–549.

3 Elsa Dorfman, interviewed by Errol Morris in The B-Side: Elsa Dorfman’s Portrait Photography, directed by Morris, Neon, 2017.

[ad_2]

Source link