[ad_1]

Still from video for Oneohtrix Point Never’s “Black Snow.”

Large yellow cans of the kind that evoke nuclear waste disposal greeted visitors to the Park Avenue Armory on Tuesday night for the first of two concerts (the second is Thursday) in service of a new album with much say about the world and ways it might look to wiser, better observers from beyond. The creator of it all is Oneohtrix Point Never, a.k.a. Daniel Lopatin, a New York-based musician whose synthesizer-inclined electronic sound has grown in ambition and scope over the years. Elements of the show—with abstract panels for projections in front of swollen inflatable forms and sculptures hanging from the ceiling—could adapt well to the environs of an art gallery. And certainly no aspect of Lopatin’s output lacks for the kind of expositional grounding and interdisciplinary connections that power many lesser bodies of work.

One such connection is to an artwork by Jim Shaw: The Great Whatsit (2017), a painting of three women staring in otherworldly wonder before a glowing laptop that graces the cover of the forthcoming Oneohtrix Point Never album Age Of (due out June 1). “Hey, you should go check out this Jim Shaw show at Metro Pictures,” Lopatin recalled his manager imploring him. “I don’t usually make gallery rounds, but she encourages me. I’m always like, ‘No, I’m just going to look at it on the internet, like I do everything.’ It’s horrible.”

Cover of Oneohtrix Point Never’s Age Of.

WARP RECORDS

But he made it out to Shaw’s 2017 show at the Chelsea gallery and saw an image that stopped him cold. “It was an awakening, standing in front of a painting after hibernating while making a record and not really being in the world,” Lopatin said. “It became very apparent to me right when I saw it that it was an allegory for the album.”

Shaw’s alternately grand and sardonic title The Great Whatsit jibes with Age Of, which stands in for the foible-filled impulse toward naming epochs and eras that are, in the grand scheme of things, indifferent to the particulars and trivialities of the human enterprise. “It’s the sort of grandeur of staring into nothingness at a lack that needs to be filled, a fundamental desire for an answer,” Lopatin said. “Jim swaps in a MacBook for what could have been some other object 10 or 20 years ago. It could be anything, and it would still glow. That’s the idea of ‘age of . . .’ The idea that we use that distinction amuses me to no end.”

Lopatin was holding forth in the lobby lounge of the Algonquin Hotel, the Midtown Manhattan landmark where the storied Algonquin Round Table of wits and wags gathered in the early 20th century—see: Alexander Woollcott, Dorothy Parker, Harold Ross, and many others who circulated during the early years of the New Yorker magazine. The setting was apt for an artist who likes to swerve and relishes incongruity. (Though a kind of congruousness could be found in a classic New Yorker cartoon framed on a wall nearby, with an ink-drawn office worker on the phone bellowing, “No, Thursday’s out. How about never—is never good for you?”)

About the artwork of Shaw, Lopatin said he knew of him as part of the same milieu as Mike Kelley but didn’t really engage with him until he started looking more closely. “There was this kind of blue-collar surrealism to it,” he said. “He seems like the kind of artist who just punches in and makes stuff. And I love his gluts of work, like the big archives—big things you can’t reduce down. That appeals to me. With Jim I can never pinpoint what’s going on. It’s like a dream, things really fluctuate”—whereas work by Kelley occasions a different kind of familiarity and weight. “Maybe it’s just the fatigue of coming to terms with somebody’s canonized work after they’re gone, or just being in awe, but [with Kelley] it’s the same feeling I get with Nirvana—like, I get it. With Jim, there was something ineffable that I couldn’t figure out.”

As for art in general, Lopatin professed a preference for occasional appreciation over paying daily attention. “I think about art when I encounter it, but it’s not one of my fetishes,” he said. “I usually am able to get excited about it vis-à-vis some other personal obsession. It’s not like following sports would be for someone, or the stock market—I just encounter it when I encounter it.” And he likes it that way. “I’m really into this way of being recently, like a Twitter timeline applied to all of my activities in life. I don’t want a specific news source and I don’t want any specific obsessions. I want to disconnect from the IV drip of getting inspiration from outside sources. I don’t want to look back on my life and see it as a series of rises and crests of feeling inspired by other people. I’m into just making my own stuff, encountering things that I’m going to naturally encounter and getting excited about them if they’re relevant somehow. Fandom in general is starting to dissipate in all aspects of my life. I want to clear out the cache, the preexisting field of interlinked ideas.”

Inappropriate for the stately setting of the Algonquin but apropos for a musician who favors signal-scrambling sounds, Foreigner’s “Waiting for a Girl Like You” played over the speakers in the lounge (in a playlist that quizzically coursed through smooth jazz and aged pop songs like England Dan & John Ford Coley’s “I’d Really Love to See You Tonight”). Lopatin said he chose the location to meet because he was rehearsing his Park Avenue Armory show nearby, in the weeks leading up to the latest entry on a list of increasingly formidable moves for the music of Oneohtrix Point Never.

Oneohtrix Point Never’s “MYRIAD” at the Park Avenue Armory in New York, presented by Red Bull Music Festival.

DREW GURIAN/RED BULL CONTENT POOL

After ascending from the synthesizer-sanctuary underground, he has in recent years taken on collaborative work with the likes of FKA Twigs, David Byrne, and Anohni. And one song on Age Of, it turns out, was originally written as a demo for Usher, the R&B star. “He asked me to write something for him after seeing an Anohni show—really weird shit,” Lopatin said of the genesis of “The Station.” After sending the track, though, “he didn’t write back—but that was perfect for me because actually I got exactly what I needed out of it, which was a song that I would’ve never sat down to try to think about. How could I modulate a Jermaine Dupri kind of idea or motif through my looking glass? That was not on my mind.”

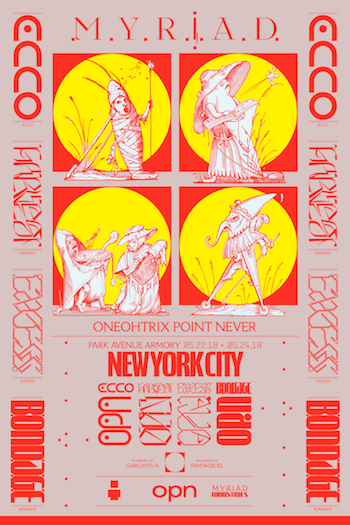

Poster for “MYRIAD.”

COURTESY PARK AVENUE ARMORY

More on his mind was the urge of many people to catalog and classify intensely complex entities with airs of authority that are laughable in the end. Consideration of that defining contemporary feature figures into Age Of as well as “Myriad,” the title given to the Armory show that presents the album’s music in a multimedia fashion (or a “concertscape,” as a program booklet puts it). The core idea for both came from watching 2001: A Space Odyssey and seeing how, in the iconic movie from 1968, aliens bequeathed the apes in the beginning with the ability to evolve through violence so as to eventually reach their (the aliens’) level. “I thought it would be interesting to invert that and do an opera that was basically about the end point of the universe,” Lopatin said. “All that’s left is the singularity, and [beings] are totally omniscient. There’s no ‘great whatsit’ scenario for them, so what they want is to loiter around this dead Earth and dream about what it might be like to be dumb like us. They run heuristics tests, which give them this orgasm to be sentimental for the feeling of Jim Shaw’s The Great Whatsit or the Age Of . . . whatever.”

Drawing on human evolution as it has transpired through early congregation to agrarian development and industrialization and other such epoch-making phenomena, Lopatin distilled the story into four epochs: Age of Ecco, Age of Harvest, Age of Excess, and Age of Bondage. How they manifest exactly in the stage show and on the album is, one might say, more than a little abstract. But Lopatin is committed to them. “What’s fun about it to me is that I can apply that epochal system to everything,” he said. “It’s become a complete source of titillation for me and all my friends. We send each other pictures all day with message like ‘E3,’ which is Age of Excess—it’ll be like a woman on Fifth Avenue with 17 dogs.”

The system, he conceded, is loose. “I call it vague formalism,” Lopatin said. “You want things to be interlinked in terms of their ability to be vital with each other but not so that they need to be in that orbit to make sense. That, to me, is much more fun—and more like the way I live my life.”

So, taxonomy is one of the main subjects of satire?

“Yeah. Remember that book that Steve Bannon claimed was his favorite, The Fourth Turning? I tried to read it and it was so bad. The tone of it was insidious, like the voice of a computer insisting on the truth about history without any sensitivity given to how complex and non-linear systems might be. It is the most pompous, most insane . . . It sounds biblical and insists over and over that this is how things happen. It was funny—it reminded me of being in temple—and I got into using that sort of taxonomy as a kind of farce to then create these little frameworks for understanding.”

Oneohtrix Point Never.

COURTESY WARP RECORDS

Talk turned over and over, as tends to happen when Lopatin get on a roll, and touched on a number of other subjects ranging from the “10,000-year radioactive conundrum” surrounding problems of how to dispose of nuclear materials (as evoked by the video for the new OPN song “Black Snow”) to philosopher Timothy Morton’s hyperobjects to the weirder recesses of art (“You know who’s the Rabelais of art right now? Jon Rafman”). And aspects of all of that figure in Age Of and “MYRIAD,” which on Tuesday night left a number of striking images in the minds of those who saw it. Hanging from the vaulted ceiling of the Armory were dripping, drooping, alien-looking sculptures by Nate Boyce (a close collaborator of Lopatin’s who also worked on the video projections). And then there was a large black mass that, late in the show, slowly started rising by way of air pumped into looming tarp-like material to make for a billowing blob that threatened to swallow the stage.

Speaking at the Algonquin about the particulars of the Age of Excess, Lopatin turned to the idea behind that blob. “It’s like the common trope in movies: some supernatural force that can’t be contained,” he said. “There’s always a government intervention or scientific intervention or a small team of renegades who are trying to either describe the consequences of its ultimate form or constrain and hold it in so it doesn’t reach DEFCON status. It makes me laugh because of how you can extrapolate from that down to the most unrelated regular shit, like trying to repress things that impede what otherwise would be everyday life to avoiding thinking about ineffable, horrible things. And then you get into the sort of social climate we’re in right now, with the rattling of cages and pointing out the sheer expansion of a tragedy that is real. We live in a time that to me seems like a blob that is getting bigger—and there’s this sense of, like, If it presses up against something, is it going to blow?”

[ad_2]

Source link