[ad_1]

Ford Madox Brown, Pretty Baa-Lambs, 1851–52.

VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

The Pre-Raphaelites have always had a tough time winning respect. Formed in England in 1848, the group has long been considered an art-historical outlier, thanks to its members’ then-unfashionable emphasis on faith and religion. And their earnest, romantic subjects can be tough to take, even for those who enjoy a bit of kitsch with their art. Consequently, exhibitions of work by adherents like John Everett Millais, and William Holman Hunt have been rare, particularly in the United States. (Museums in the United Kingdom have been more supportive.) This summer, though, the Seattle Art Museum has gallantly stepped into that void, presenting “Victorian Radicals: From The Pre-Raphaelites to the Arts and Crafts Movement.”

With that show in mind, we’re republishing an essay from the May 1964 issue of ARTnews, in which critic Allen F. Staley wrote on an exhibition of the the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s work at the Huntington Hartford Gallery of Modern Art in New York. Organized by the John Herron Museum in Indianapolis (now Newfields), it offered one of the most expansive surveys of Pre-Raphaelite art in the U.S. to date, but despite its scope, Staley was not pleased with what he saw. “Considering their meager ammunition, it was perhaps inevitable that they would fail to establish a new tradition,” he said of the group’s artists. His review follows below.

“Radical romantics”

By Allen F. Staley

May 1964

The Pre-Raphaelite painters’ best work involved an eccentric rediscovery of nature, a facet unfortunately neglected in the current survey of their art at Huntington Hartford’s gallery

The Pre-Raphaelites’ reputation has always been unstable. Within two years of the formation of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848, the pictures exhibited by Millais, Hunt and Rossetti were attracting almost unanimous abuse. Although Ruskin soon became the movement’s eloquent defender, critical obtuseness never grew into universal adulation and today, Pre-Raphaelitism stands again in generally low repute. The Pre-Raphaelites never fared well in America: an exhibition sent to New York in 1857 had little impact, and since then the American public has had only rare opportunities to see their pictures. A well-chosen few were in the exhibition of British painting at the Museum of Modern Art in 1956. Now, a large exhibition, organized by the John Herron Museum, Indianapolis, is currently at Huntington Hartford’s Gallery of Modern Art. The exhibition has been drawn entirely from American and Canadian collections; it therefore provides documentation of collecting in this area as well as a useful survey of most of the Pre-Raphaelite pictures in the Western Hemisphere. Although there are a few absentees (notably the pictures from the Bancroft Collection in Wilmington and from the Whitney Collection in the Fogg Museum, which by terms of the bequests cannot be lent) Mr. Curtis Coley has done a laudable job of scouring the country, and the exhibition includes a number of pictures previously thought to be lost.

Unfortunately, the exhibition is not likely to help the movement’s reputation. It mainly demonstrates that the best Pre-Raphaelite pictures are still in England. To see Pre-Raphaelitism, one must go to Manchester, Birmingham and Liverpool, the centers of Victorian commercial prosperity. Furthermore, American interest in Victorian painting has always been subordinate to that in Victorian writing, with the result that the painters who have been bought by Americans are those with the strongest literary ties: Rossetti and Burne-Jones.

The overwhelming preponderance of these two artists in the current exhibitions reflects the balance of American collections, but it presents a very distorted picture of Pre-Raphaelitism. Rossetti was the most interesting personality of the group, but he stopped exhibiting in 1850, two years after the formation of the Brotherhood. To the public of the 1850s, the decade when Pre-Raphaelitism was an important issue, Rossetti was underknown. Burne-Jones’s historical significance begins with the Grosvenor Gallery exhibitions of the later 1870s, and he belongs much more to late Victorian estheticism than to mid-century Pre-Raphaelitism. He was not a member of the Brotherhood; his earliest works were strongly influenced by Rossetti, but most of his eclectic art has little to do with Rossetti and nothing to do with the rest of the movement. That Burne-Jones should be by far the best represented artist in the exhibition simply perpetuates a misconception.

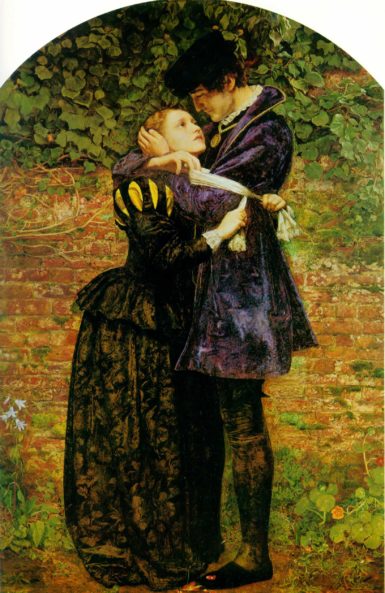

John Everett Millais, A Huguenot on St. Bartholomew’s Day Refusing to Shield Himself from Danger by Wearing the Roman Catholic Badge, 1851–52.

VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Pre-Raphaelitism, as it was defined by Ruskin and understood by his contemporaries, meant Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais of the original Brotherhood, and a number of associated artists, of whom Ford Madox Brown was the most important. To see this fundamental side of Pre-Raphaelitism, we might examine three pictures exhibited by these artists at the Royal Academy in 1852. The most popular of them was Huguenot by Millais, which now belongs to Mr. Hartford. Its full title in the Academy catalogue was A Huguenot, on St. Bartholomew’s Day, refusing to shield himself from danger by wearing the Roman Catholic Badge, and it was accompanied by a historically explanatory quotation. The subject combining historical reconstruction, moralistic storytelling, Protestant piety and saccharine sentimentality is typically Victorian—and not peculiarly Pre-Raphaelite. However Millais began the picture by painting the background directly from nature, before deciding what the subject would be, and the minutely painted bricks and foliage are a tour-de-force of observation, dominating the picture. The painting hardly has a composition: it is airless, spaceless and, though bright, lightless; figures, moss, bricks, and foliage all crowd together to the surface. The myopically close attention to detail is naturalism of a very limited, primitive sort; nonetheless, it does indicate a desire for direct, unsophisticated contact with the physical world and a willingness to sacrifice a great deal of pictorial tradition to get it. Youthful directness and technical virtuosity, when not overlaid with sentiment, make Millais’ early works among the most appealing of Victorian paintings. However, it was sentiment that made the Huguenot his first popular success; as such the picture marks the beginning of Millais’ split with Pre-Raphaelitism and contains the seeds of the decline in his later art.

Fortunately Millais’ colleagues did not have the same feel for the public pulse. Ford Madox Brown was consistently so badly treated at the Royal Academy that after 1853 he stopped showing there and became the leader of a number of Pre-Raphaelite efforts to organize independent exhibitions. His Pretty Baa-Lambs, also called Summer’s Heat, is as remote as Millais’ Huguenot is accessible. When exhibited in 1852, it found no admirers, because its “meaning” was considered inscrutable. However Brown, writing thirteen years later, claimed that the picture had no meaning other than the obvious one: “a lady, a baby, two lambs, a servant maid and some grass,” and he went on to attack “philosophical intentions” as the essential element of painting: “I should be much inclined to doubt the genuineness of that artist’s ideas, who never painted from love of the mere look of things.” This refreshingly un-Victorian attitude pervades much of Brown’s art. The Pretty Baa-Lambs was painted entirely out in sunlight, thus anticipating pictures like Monet’s Women in the Garden by well over a decade. Brown’s only intention was “to render that effect as well as my powers in a first attempt of this kind would allow.” Consequently, if the picture has a forbidding stiffness, it also has a consistency and a sense of real experience remote from Millais’ studio-posed figures and relatively decorative filigree of foliage.

Brown was the first among the Pre-Raphaelite group to paint the whole picture—figures and landscape—entirely out of doors, but he wrote that the Baa-Lambs had been painted “at a time when discussion was very rife on certain ideas and principles in art, very much in harmony with my own views, but more sedulously promulgated by friends of mine.” The ideas were of outdoor naturalism; their most ardent promulgator was Holman Hunt. Today, it is difficult to see Hunt other than as a preacher. In his Hireling Shepherd, also exhibited in 1852, the symbolic embellishments referring to pastors who neglect their duty have become notorious. Unlike Brown, Hunt was quite happy to have his picture read as a sermon; however he did claim that his first purpose had been to paint a real shepherd and a real shepherdess in a sunlit landscape, without allegorical intention. When exhibited, the Hireling Shepherd did not strike critics as being packed with meaning; rather they primarily damned its “repulsive” realism, in language comparable to that being used at the same time for Courbet. The shepherd and shepherdess were painted in the studio and are somewhat separate from their background, but they do have a tough, unidealized ruggedness unprecedented in England, and, if we look past them, the landscape combines a remarkable airiness and luminosity with the sunburnt richness of the English countryside.

William Holman Hunt, The Hireling Shepherd, 1851–52.

VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

According to Hunt’s history of the movement, Pre-Raphaelitism was largely inspired by his reading Ruskin’s Modern Painters in 1847. One of Hunt’s resolutions as the bearer of the new evangel had been to paint a picture, “the whole of doors, direct on the canvas itself with every detail I can see, and with the sunlight brightness of the day itself.” He and Millais did begin painting their backgrounds out of doors, and, as we see by a picture in the exhibition, Hunt’s Haunted Manor, 1849, they began making careful studies from nature for their own sakes, as Ruskin urged. The picture and its companion, the Kingfisher’s Haunt by Millais, provide examples of Hunt and Millais working side by side form the same natural motif, which show the two personalities, within a year of the Brotherhood’s formation, already further apart than Renoir and Monet mutually painting the same subjects in the late 1860s. Hubnt, the strongest member of the Brotherhood, is blunt and direct, painting the subject frontally and giving it a certain heaviness; Millais, the precocious talent, is thinner, more elegant and unconcerned with physical solidity. Even more striking are the different backgrounds, which seem to be later additions. (They could be considerably later: Millais’ picture was first seen in 1854, when Madox Brown noted it in his diary as recent; Hunt’s was first exhibited in 1856). In place of Millais’ mildly sentimental figures and innocuous bit of forest, Hunt’s background is full of golden light which transfigures the prosaic landscape into a hyper-real vision. Truth of local color was a basic Pre-Raphaelite tenet, but Hunt also concerned himself with the effect of light upon color. In the Hireling Shepherd the clouds are pink and the shadows become blue; and other of Hunt’s pictures are full of dazzling prismatic colors which still can be shocking. The spectacular effects of light, packed space and glaring colors of these pictures give them an unreal quality despite their literalness. The unreality is the result, however, not of an abstracting intention, but of an extraordinarily vivid perception of natural phenomena, which puts spiritual value into the experience.

Hunt soon channeled his ardor into religiosity, but the essentially Pre-Raphaelite quality is this heightened awareness. As exemplified in varying degrees in Milllais, Hunt and Brown, it is directed toward “the look of things;” the young Rossetti’s more literary and archaizing drawings have much of the same stress turned inwards. To awareness, the Pre-Raphaelites added little more than keen sight and hard work. Unallied to any strong pictorial tradition, these qualities could guarantee little, and with the passing of the artists’ youth, their art rapidly declined. Hunt, Millais and Rossetti all did their best work well before their thirty-fifth birthdays; their long later careers were financial successes, but for the most part artistic doldrums. Millais pandered commercially. Rossetti repeated over and over his grimacing women. Hunt continued painting highly elaborated pictures, but they seem heavy-handed after the sensitivity of the Hireling Shepherd.

Even the early years contain much that is tentative and uneven. If we make the inevitable comparison, Courbet and the Impressionists seem old-masters, in the European tradition, enriching it and drawing assurance from it, while the Pre-Raphaelites seem cut off. They lack assurance; there is always something insecure and inconsistent about their art, as if the actual handling of the paint made them nervous. However, what they lack in Continental suavity, they make up to an extent in knotty individualism. Precisely the element of nervousness—absence of sustaining tradition—keeps their art alive. Holman Hunt and Madox Brown almost literally tried to re-invent the whole art of painting in each picture. Considering their meager ammunition, it was perhaps inevitable that they would fail to establish a new tradition. But in individual pictures, the record of their integrity of the precarious attempt—and of the sheer effort involved—is often so strong that the pictures establish their own values, if only as witnesses to their own creation. By ultimate standards, the Pre-Raphaelites may be noble failures, but they deserve better than the misrepresentation which has been their usual fate in America—and which the current exhibition does little to avoid.

[ad_2]

Source link