[ad_1]

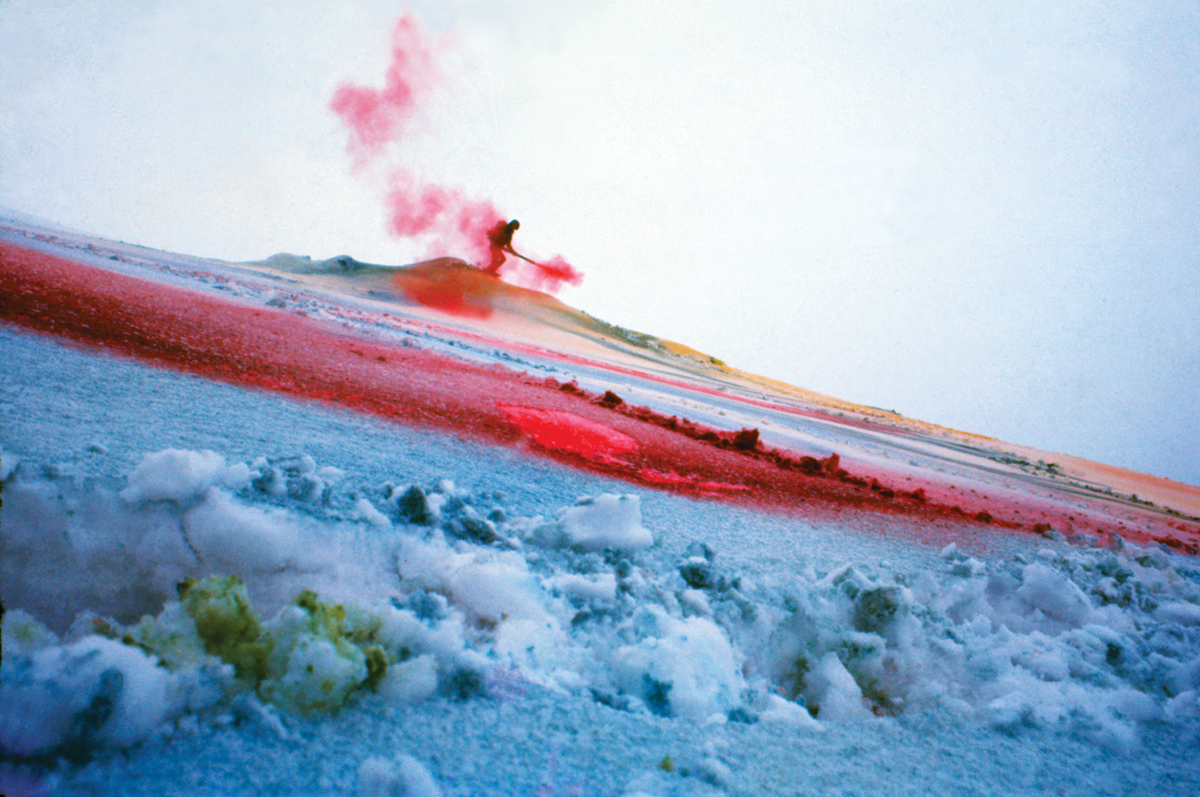

GUN, Event to Change the Image of Snow, 1970, documentary photograph of performance art. Japan Society.

©HANAGA MITSUTOSHI

As spring arrived in New York, there was barely a corner of Manhattan without a great show to see. The highest-profile among them was the excellent Hilma af Klint retrospective at the Guggenheim, which garnered the museum’s highest-ever attendance, but that show was only the most visible of many exhibitions that reexamined the history of modern art, and expanded the canon.

Others, like the Japan Society’s show of 1960s conceptual art curated by Reiko Tomii, flew under the radar. Tomii is a truly influential curator who collaborates with contemporary artists like Ei Arakawa. Her deep archival research for “Radicalism in the Wilderness” brought three artists and collectives to light: GUN, the Play, and Matsuzawa Yutaka are far less known than more urban Japanese movements like Gutai or even Hi-Red Center. The material is fascinating on its own (exhibitions that happened only in the mind; paintings on snowy fields) and was made more so by Tomii’s demonstrating how these artists intersected with international conceptual artists like Stanley Brouwn and Yves Klein. Parts of the exhibition were not for the impatient, however: one room contained a dozen vitrines filled with historical papers.

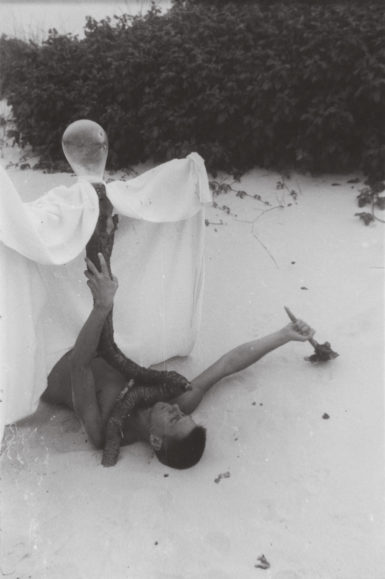

Many of the best shows in town featured women artists, particularly painters. For Mary Beth Edelson’s exhibition at David Lewis, the gallery’s main space hosted a series of life-size shaped paintings from the mid-1970s, called the “Great Goddess Cut-Outs,” depicting historical feminist figures and goddess archetypes. Some evoke birds, or the sun and stars; others are geometric or mandalic. With one of them set in the entrance of the main gallery, an unbroken circle surrounded the viewer. In the front gallery, black-and-white photographs from the same era showed Edelson nude in various sacred landscapes and suggested the work of both Ana Mendieta and Francesca Woodman. It was powerful stuff.

Mary Beth Edelson, Public Ritual, n.d., gelatin silver print, 21¼” x 21¼”.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND DAVID LEWIS, NEW YORK

Over at the gallery Eric Firestone Loft, Mimi Gross’s enormous colorful figurative paintings were an absolute knockout. They recall the collective subjects of 17th-century Flemish group portraits—but instead of murky, monochromatic trade guilds, Gross painted the Grand Street Girls (1963), with their floral dresses, crop tops, and teased beehives, and boho chicks like Katherine Under the Persimmon Tree (1961), with her paisley blouse and cigarette, all in supersaturated oranges and greens. Her subjects were beatniks and proto-hippies living in downtown New York and rural Italy. A wall of framed notebook pages testified to the strong influence of Matisse and van Gogh on her Madonna-like women and rustic outdoor cafés. That Gross was married to Red Grooms, and very young (in her late teens and early 20s) when she made the paintings in the show seems neither here nor there in relation to these colorful and sunny works, except to add to the aura of bohemian young love.

At Zwirner, Alice Neel’s daughter-in-law Ginny Neel provided a new look at a beloved master. Neel’s visceral and brilliantly observed painting has never looked as human as in this presentation, in which naked bodies and babies take center stage. Including some rarely seen early paintings, the show felt vast, and was a pleasure to see. Meanwhile, March Avery (Barnard ’54) had a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it three-week show of poetic paintings made between 1955 and 1978 and depicting new parenthood (think Mary Cassatt in a Milton Avery palette), at her alma mater’s own Louise McCagg Gallery. There were also some of her earthy ceramics, including a memorable artichoke. Given that we live in an age of rediscovery, my prediction is that we’ll see the paintings displayed by a smart commercial gallerist sometime soon.

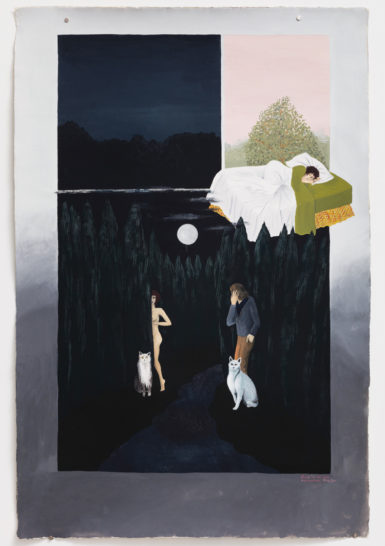

Mira Schor, Dream, 1972, gouache on paper, 40″ x 20″. Lyles & King.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND LYLES & KING, NEW YORK

There was a fabulous Mira Schor show at Lyles & King. Schor studied with Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro in the feminist art program at California Institute of the Arts. Made primarily in 1971 and ’72 while she was at CalArts (one reads “Goodbye CalArts!—May 19, 1972”), these paintings are dreamlike self-portraits of a fierce and often nude young woman making her way through a lush landscape populated by penguins, horses, bears, and automobiles, and are reminiscent in attitude of early Leonora Carrington. A little West Coast peeks through in the paintings’ super-flat finish and car-paint palette—Alice dropped into a wonderland of Ed Ruscha’s gas stations.

Vivian Suter, at Gladstone, looked fantastically rich and alive. The swooping canvases hung from the ceiling and on every wall the way she has always shown them—unhooked from stretcher bars as perhaps a deliberate refusal of a patriarchal constraint, a bit like painting’s version of bra burning. The gallery was soaked in color, and figuration and abstraction cohabited happily. A little outpost of the paintings flapped around outdoors near the Whitney Museum entrance to the High Line elevated park. Uptown, an elegant show of Luchita Hurtado at Hauser & Wirth brought the recent West Coast museum star to New York. The show focused on her very early drawings and paintings, some of which are slight—but there were some lyrical paintings of deer and women’s bodies, and drawings of primitivist figures. I can’t wait for part two: the later work.

Leonor Fini, Les Aveugles (The Blind Ones), 1968, oil on canvas, 28⅛” x 45½”. Museum of Sex.

COURTESY WEINSTEIN GALLERY

There was a lovely Leonor Fini show at the Museum of Sex—her work is terrific—self-possessed self-portraits with an owl and in some truly post-Freudian costumes, and a portrait of Jean Genet. The curator, Lissa Rivera, did a good job with Fini’s first American museum survey, but why it couldn’t have been at MoMA or another major museum is beyond me. At another non-art museum, the New-York Historical Society, was Betye Saar’s haunting history of slavery and lynching. In assemblages dating from 1997 to 2017, washboards, mammy dolls, and white sheets flickered between innocence and malevolence.

In photography, the beloved Barbara Ess got her second solo show in less than a year—“Someone to Watch Over Me” at Magenta Plains. (The first was a few months ago at the terrific 3A Gallery.) Ess is an artist’s artist. Subtly pixelated photos of everyday objects—flowers, an apartment window—printed with a grain as if blown up from video footage, demonstrated her keen eye for the details and texture of modern life. Still, the formal hang didn’t quite get at the feeling of her zine, Just Another Asshole (recently reprinted by Primary Information), or her cult band, Y Pants. Like Warhol, Ess is truly an “intermedia” artist (think, Warhol’s involvement with the Velvet Underground and founding of Interview magazine). And at Janice Guy’s newish uptown space, a subtle show of photographer Judy Linn made the case for her idiosyncratic eye. With the photographs unframed and hung at various heights and in diverse sizes across the repurposed Harlem apartment, it was almost like a short concert in which the work overall establishes the musician’s range: MTV Unplugged for photography.

At Red Bull Arts New York, the first posthumous retrospective of multimedia artist Gretchen Bender brought a larger outing of her work, following a memorable series of installations at the Kitchen and in the 2014 Whitney Biennial. It included her mounted photographic panels and a lot of context in the form of interviews with Pictures Generation artists, collaborators, and art historians (did you know Hal Foster’s wife, Sandy Tait, worked on a piece with Bender—Volatile Memory, 1988—that features Michel Auder and Cindy Sherman?). Despite the fancy installation, to me the most devastating were Bender’s simple sculptures running single-channel TV stations with phrases printed on the screen: “Public Memory” over a workout program, “Revolution” over a car insurance ad.

PaJaMa, Paul Cadmus, ca. 1945, gelatin silver print, 7″ x 5″. Museum of Modern Art.

©2019 ESTATE OF PAUL CADMUS/MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK

For a different take on what we think of as modern art, there was “Lincoln Kirstein’s Modern,” at the Museum of Modern Art, a collection show as sci-fi: it laid out an alternative history of the museum itself. There was some wonderful campy stage and costume design, including a pastel by dancer Vaslav Nijinsky, and a certain focus on South America (by Europeans like Jean Charlot and Tina Modotti but also José Clemente Orozco). Most notably, a number of George Platt Lynes photographs and Paul Cadmus drawings of male ballet dancers highlighted the influence of gay men in the formation of modern art. This isn’t exactly a revelation, but it was gratifying to see it presented so openly. What really got me were the photographs: early pictures of Gothic homes in New England from Walker Evans’s famous 100-photograph show at MoMA in 1938, taken before he traveled with James Agee on assignment for Fortune magazine to shoot for what would become the 1941 book Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, and a Paul Cadmus collaboration with his lover and his lover’s wife under the name “PaJaMa,” from their combined initials.

Another place to see paths of modern art not taken was the Met Breuer’s weird Lucio Fontana show. There were some incredible canvases laden with colored Murano glass, a lot of baroque ceramics, and some truly surprising experiments Fontana made before reaching his signature Zorro-like canvas-slashing style. It seemed a good place for an artist to steal some ideas.

At Gagosian gallery, the late Shusaku Arakawa, an underground favorite, got a mammoth show of his large-scale paintings, “Diagrams for the Imagination.” Known for his collaborations with poet Madeline Gins, Arakawa came of age as a post-Duchampian just after Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, and this show made a strong case for considering his paintings in relation to theirs. I loved those with his deadpan stenciled instructions (“These arrows indicate almost nothing. Re-arrange the numbers any way you like,” reads one) and how, in his work, a painting’s surface is nothing like any traditional perspectival window—one looks like a giant vision test. Expanding on the understanding of Gins and Arakawa’s work, recently explored in “Eternal Gradient” at the Arthur Ross Architecture Gallery at Columbia University, the Gagosian show rewarded multiple viewings.

Jasper Johns, Untitled, 2018, oil on canvas, 50¾” x 34⅛”.

©JASPER JOHNS AND VAGA AT ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NY/COURTESY MATTHEW MARKS GALLERY

Getting back to Jasper Johns for a moment, he had his own show of new work on view at Matthew Marks. It was good—replete with his hermetic paintings that point back mostly to other Johns paintings. They have the feel of a riddle about to be solved. Faces young and old in profile shape a vase; nearly identical paintings, one in black-and-white and one in color; a flat painting in which a star map appears, one edge peeled up—the work is relentlessly and terrifically American, referencing everyone from William Harnett to Robert Rauschenberg but never looking for a minute like anything but Johns.

Over at Marks’s other location, I wasn’t the only person in town to love Vincent Fecteau’s exhibition, “Magic Ben Big Boy: Lutz Bacher, Nayland Blake, Vince Fecteau.” Fecteau was assistant to both Bacher and Blake in the 1990s, and he fabricated the work in all three rooms. From Bacher, Fecteau chose a giant naked baby in cloth, from Blake a sculpture of an old crone in a house from which spill artificial roses. Fecteau himself contributed cutouts of cats and the occasional E.T., pasted directly onto the gallery walls. At the front of the gallery was the original checklist from a Fecteau show from 1990 including the original prices—each piece was $200 or $300. The whole arrangement was canny and sweet and low-fi, and a subtle take on gender politics.

Nostalgia for the ’90s—and its lower-budget art world—was also my overwhelming feeling at a lovely Ben Morgan-Cleveland show at Kai Matsumiya. The former co-owner of the small gallery Real Fine Arts put up romantic pinhole camera photos of forests in which simple words—“the,” “you,”—are formed by sticks and branches. Real Fine Arts closed last year, like so many other lively, experimental spaces. Meanwhile, the Shed, a $475 million behemoth arts venue just opened in Manhattan’s Hudson Yards and it was maybe the one corner of New York this spring where I couldn’t find a good show.

A version of this story originally appeared in the Summer 2019 issue of ARTnews on page 94 under the title “Around New York.”

[ad_2]

Source link