[ad_1]

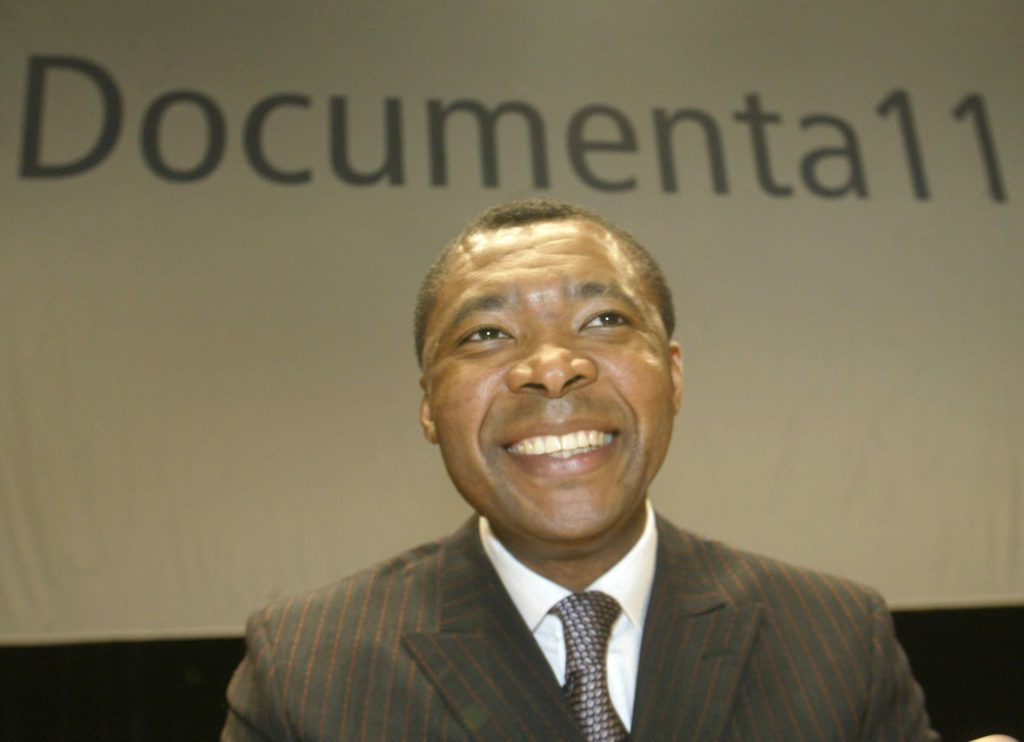

Enwezor at the opening of Documenta 11, which he curated, in Kassel, Germany, in 2002.

JOERG SARBACH/AP/REX/SHUTTERSTOCK

Curator Okwui Enwezor, whose incisive, free-thinking, and ambitious exhibitions were essential in pushing the art world to embrace a global view of contemporary art and art history, has died at the age of 55. He had been battling cancer for years. Among the first to share news of his passing was the Venice Biennale, whose 56th edition he curated in 2015.

Enwezor was the first African-born curator to organize the Biennale, a show that began in 1895, and the first non-European to oversee Documenta, the every-five-years exhibition in Kassel, Germany, which he organized in 2002. The latter show, Documenta XI, defined his curatorial sensibility: venturesome, unabashedly intellectual, and intent on rethinking how institutions operate.

In the run-up to the opening of Documenta in June of 2002, Enwezor presented what he termed platforms—conferences, seminars, and other projects—in Berlin, Vienna, New Delhi, St. Lucia, and Lagos, Nigeria. Unlike past editions of Documenta, Enwezor’s exhibition was not dominated by artists from Europe and the United States, and included a significant quotient of African, Asian, and South American artists.

Discussing his career with Melissa Chiu at the Asia Society in New York in 2014, he said, “When I started, I always had what I thought was a change agenda.” He worked tirelessly over the course of more than 30 years to fulfill that mission, indelibly shaping the way art is presented and taught.

“He was one of the leaders of, let’s call it, the free curatorial world—one of the people who believed in intelligence and scholarly research and passion and the power of the curatorial,” Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, the director of the Castello di Rivoli in Turin, Italy, and curator of Documenta 13 in 2012, said by phone this morning.

Curator Cuauhtémoc Medina said on Twitter that Enwezor “was a major force of contemporary culture. His achievement as curator of some of the most important global exhibitions of the last decade punctuated the emergence of the South as a global cultural movement.”

Enwezor was born in Calabar, Nigeria, in 1963, and grew up in Enugu. He moved to New York in the early 1980s, and earned his undergraduate degree in political science from what is now New Jersey City University. He wrote and performed poetry, and like so many in that field, he soon found his way into art criticism. In the early 1990s, he began curating shows, and in 1994, while based in Brooklyn, he cofounded Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art.

Asked about that name in an interview with the Vitra Design Museum, Enwezor said he was “searching for a term that projected an aesthetic horizon, but would also constitute a forum of ideological resistance.” He explained that Nka, “in Igbo, the language I grew up with in Eastern Nigeria, means to create, to make, to invent. It also means art. Then in Basaa, a language in Cameroon, Nka means discourse. People oftentimes ask me, ‘When was the first time you went to a museum?’ As if a museum is the only space where one encounters art! Calling the magazine Nka was a way of disarming this particular notion.”

In 1996, Enwezor organized “In/Sight: African Photographers, 1940 to the Present” at the Guggenheim Museum’s location in the SoHo section of Manhattan. The show featured 30 artists, among them Seydou Keïta, of Mali, and Samuel Fosso, of Nigeria, both of whom have since been canonized. Max Kozloff, writing in Artforum, said that the show “broke ground here, offering practically all its subjects a U.S. debut,” and Holland Cotter, in the New York Times, termed it a “mandatory stop.”

Soon after, he curated the 2nd Johannesburg Biennale, which opened in 1997. It was one in a string of the closely watched international exhibitions he oversaw over the coming two decades; he also went on to organize the 2008 Gwangju Biennale in South Korea and the 2012 Triennale at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris.

In 2005 Enwezor was named dean of academic affairs at the San Francisco Art Institute, where he would remain until 2009. And as an adjunct curator at the International Center of Photography in New York, he organized trailblazing exhibitions like “Snap Judgement: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography” in 2006 and “Rise and Fall of Apartheid: Photography and the Bureaucracy of Everyday Life” in 2012. “The role of photography in the struggle against apartheid is far larger than we can really imagine,” Enwezor said, discussing that last show in ARTnews. “It became one of the most persuasive, instrumental, ideological tools.”

In 2011, Enwezor became director of the Haus der Kunst, the sprawling kunsthalle in Munich, Germany, which under his watch hosted solo exhibitions of work by Stan Douglas, Georg Baselitz, Ellen Gallagher, James Casebere, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Hanne Darboven, Frank Bowling, Matthew Barney, and many more, as well as, in 2016, “Postwar: Art Between the Pacific and the Atlantic, 1945–1965,” an unprecedented survey of the story of postwar modernism around the world that included some 350 pieces by more than 200 artists.

His tenure at Haus der Kunst ended abruptly. In mid-2018, the Bavarian state announced that he would leave the institution three years before his contract was up because of health concerns. Claims were aired in the press about budget shortfalls, which he adamantly denied.

“It’s an insult, yes,” Enwezor said of the statement disclosing his departure. “I am almost perplexed. The achievements and successes of seven years are swept under the rug. I have worked with passion to raise the profile of this museum, especially internationally. We have achieved so much, not only the exhibitions, performances, concerts, discussions, not just what is visible, but also the scientific research, the scholarships we have awarded.”

Enwezor, even while ill, remained a close confidant to artists and curators of many generations, and a reliable presence at their exhibitions. For this year’s Venice Biennale, which opens in May, he had been serving as strategic adviser for Ghana’s first-ever national pavilion.

In a 2014 profile in the Wall Street Journal, Enwezor said of his career, “There was nobody who quote-unquote opened the doors. The doors were resolutely shut. I’m as surprised as the next person about where I am.”

Enwezor did open doors, influencing many Eurocentric museums to make strides in collecting and highlighting modern artists who hailed from historically under-reprsented regions. Noting “a new generation of curators and museum professionals with different fields of knowledge” that was coming of age, in a 2017 interview, Enwezor said, “I hope these people will give institutions the opportunity to think about how to complicate the narrative of societies with colonial affiliations, which necessarily are mixed societies. If we have an open mind, Western art doesn’t have to be seen in opposition to art from elsewhere, but can be seen in a dialogue that helps protect the differences and decisions that present the material, circumstances and conditions of production in which artists fashion their view of what enlightenment could be.”

“I see my role not just simply to be a curator and make exhibitions, I want to be an enabler for my curators,” he said in his 2014 interview with Chiu, discussing his position as director of Haus der Kunst. “I want to be . . . the backup singer for their solo acts.”

[ad_2]

Source link