[ad_1]

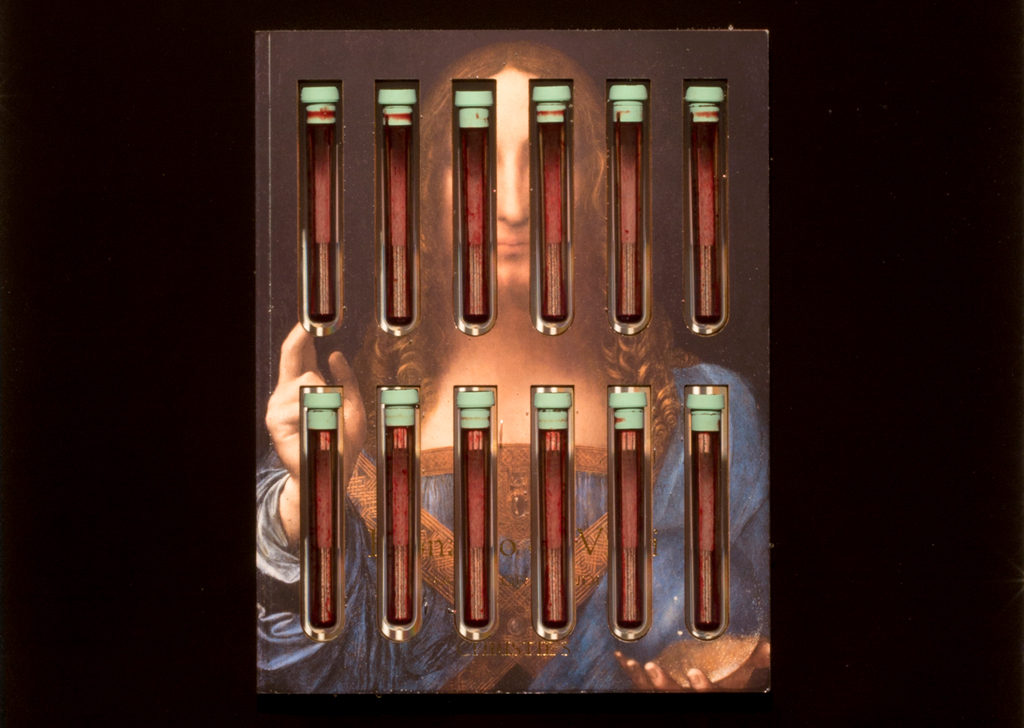

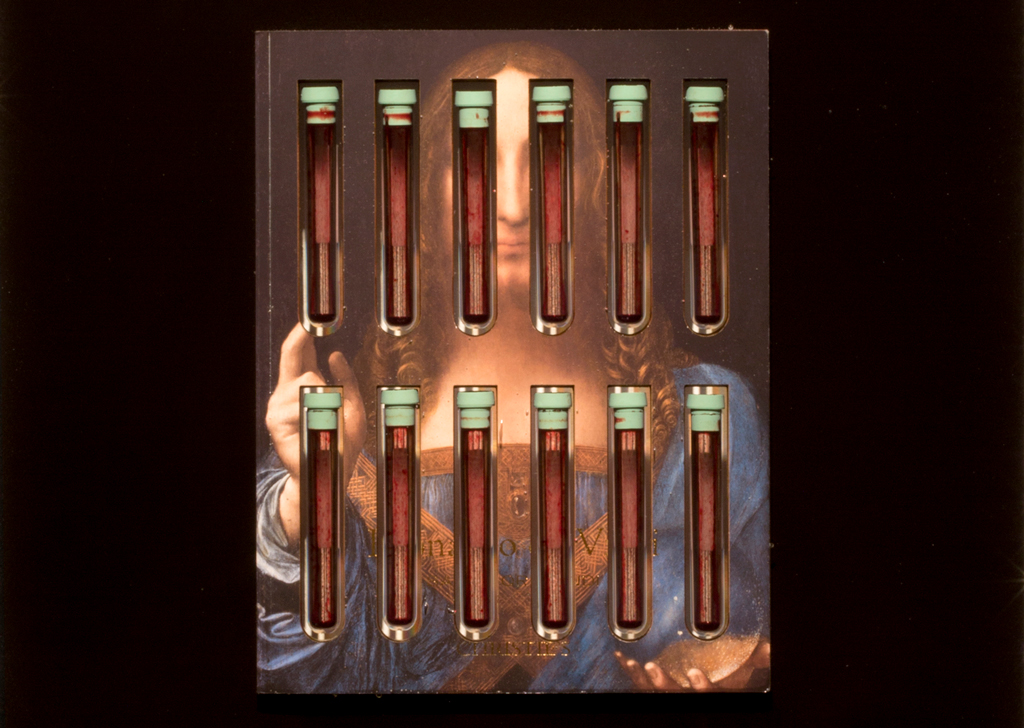

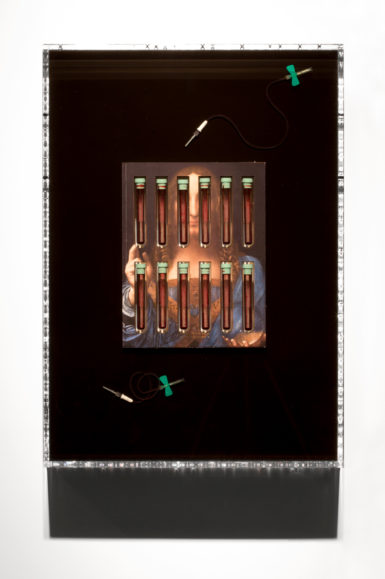

Jordan Eagles, Jesus, Christie’s (detail), 2018, Christie’s sale catalogue, medical tubes, needles, and blood in plexiglass and UV resin.

COLLECTION OF THE ARTIST

One year ago today, Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi sold for the astonishing price of $450.3 million at Christie’s in New York. The sale of that painting of Jesus Christ, as envisioned circa 1500, inspired much fanfare, conspiracy-level speculation over the identity of the buyer, and at least one new artwork: Jesus, Christie’s (2018) by Jordan Eagles.

For his piece—newly on view at the Leslie-Lohman Museum in SoHo, where it will remain through the end of December—Eagles took the auction catalogue dedicated to Salvator Mundi and laser-cut 12 slits into the cover to hold empty blood-collection tubes. The catalogue with the painting’s image was mounted on a black background and surrounded by needles, and then encased in resin and plexiglass.

In an era of rising auction prices, Jesus, Christie’s can be read as a critique of the art market. But that would be just one facet for Eagles, whose work has long centered around the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s blood-donation policies for men who have sex with men (MSM). “This is not an attack on Christie’s,” Eagles said earlier this week at the museum, after installing his work. He conceded that the piece is at least somewhat “about the astronomical price” of the Leonardo sale, which “indicates where our priorities are as a society.” He continued: “Almost half a billion dollars is spent on a painting. How could those funds have been used to do good in the world?”

Jordan Eagles, Jesus, Christie’s, 2018, Christie’s sale catalogue, medical tubes, needles, and blood in plexiglass and UV resin.

COLLECTION OF THE ARTIST

But Eagles pointed out that Salvator Mundi translates to “savior of the world” and said he wanted to connect that idea with his advocacy for lifting the one-year celibacy requirement for potential MSM blood donors—in the interest of “all the lives that could be saved through the blood of men who have sex with men.”

Prior to the establishment of the one-year celibacy rule in 2015, would-be MSM donors weren’t allowed to donate blood at all, a fate that critics considered a vestige of a prejudicial past. A study published in 2014 by the Williams Institute estimated that lifting the lifetime ban and instituting a 12-month deferral period would add 317,000 pints of blood to the nation’s yearly supply, whereas lifting the ban entirely would nearly double that, to 615,300 pints—which could help save over 1 million lives. In any case, Eagles believes that donors should be able to give what they want for the sake of the overall good. “My entry point with this is thinking of Jesus Christ as the greatest blood donor of all time, having shed his blood on the cross for his sins of all mankind,” Eagles said of his work, whose 12 embedded tubes refer doubly to Jesus’s 12 apostles as well as the number of months needed to meet the celibacy requirement.

Gonzalo Casals, the Leslie-Lohman Museum’s director, said Eagles’s engagement of “art market dynamics, Christian values, and illogical blood donation policies affecting queer and bisexual men serves as a metaphor for the complex zeitgeist of our time.”

Jesus, Christie’s is part of a larger body of work that Eagles began after the recent high-school shooting in Parkland, Florida, which triggered feelings he experienced in the aftermath of the Pulse Orlando shooting in 2016. With a series of works still being conceived, Eagles said he wanted to look at “bloodshed and the wasted potential in the lives lost that comes out of carnage.”

He also pointed to recent “unsettling” plans by the Trump administration to move $260 million from HIV/AIDS prevention, cancer research, and other programs to cover the costs of holding migrant children in detention centers. “I think the teachings of Jesus are ones of acceptance [and] healing the sick—not alienating people,” the artist said. “He would purposely go and help the people who would be the ‘others.’ “

He wondered what Jesus would have wanted the millions paid for a painting of his likeness to be used for. “The irony is that the image is of Jesus,” Eagles said. “Any painting could have sold for $450 million. It just happens to be the savior of the world.”

[ad_2]

Source link