[ad_1]

The taste of Spanish sugar cookies lingered as Michael Stipe lit a stick of incense—a Shoyeido-brand varietal from Japan whose bouquet suits the serenity of its name, “Beckoning Spring”—and held it up to his forehead. Doing so for a moment with your eyes closed, he said, is a good way to send a thought out into the world.

The occasion was a sort of makeshift ritual to mark the “ascension date” for Jeremy Ayers, an old friend of the former R.E.M. singer and current artist-of-many-trades. Ayers, who died in 2016, was an important figure in Stipe’s coming-of-age as an early muse in Athens, Georgia, who had lived large in previous lives, including as one of Andy Warhol’s superstars (under the name Sylva Thin) in New York. As it happens, Ayers’s spirit is what brought the two of us together for the first time, for an interview onstage in Durham, North Carolina, in 2017, during a Moogfest music festival at which Stipe presented a tribute in the form of a video installation titled Jeremy Dance.

That led to another talk as part of Moogfest the following year and then a couple stories about Stipe’s photography book Volume 1 and his most recent gallery show in Brooklyn, which featured everything from cardboard alarm clocks and pictures of Neil Armstrong’s wife to a kimono-making apparatus and a light bulb of a kind he had once (ill-advisedly) eaten as a child.

All of which is a roundabout way of saying: Michael Stipe has a habit of drawing disparate elements together into spaces he makes feel ready for ritual and at least a little bit different than any other kind of space I’ve ever been in before. Connections seem to fall into place around him, magnetized somehow, so that an afternoon in his studio can jump from talk of Spanish cookies (Ines Rosales Sweet Olive Oil Tortas) to puzzling over the Jupiter’s Square (a magical mathematical arrangement in which all the numbers in different directions add up to 34) and follow a perfectly sensible through line.

Stipe’s new photography book, Our Interference Times: A Visual Record, takes that tendency to the extreme. Its subject matter is scattered, with photographs of things too diffuse to be circumscribed. But it follows a sequence, and storylines of a sort start to coalesce after you flip through a few times—even if still more than a little elusively.

“I thought maybe I was overstating my points too much and being a little too clear,” Stipe said of the book a few weeks ago, in his East Village studio. “I thought, Maybe I need to roll back a bit on how obvious I’m being. It felt very mainstream. But then I woke up one morning and looked at a rough early copy and was like, Holy shit, this is really odd!”

The book is intentionally dense and disorienting, with every image running full-bleed to the edges of the page and many of them turned at angles that are clearly wrong but in ways that can it make it hard to know which other way might be right. The only words appear in the back in a brief index identifying certain subjects and locations, but even those can be oblique. Some examples: “Modernist wall with skeleton glove, Berlin” and “Peep in microwave, Athens.”

Sarah Stacke

Stipe recalled a revelation he had when Thomas Dozol, his longtime partner and a fellow photographer, told him, “You don’t have a hierarchy of anything. You don’t have a filter that categorizes. A grate on the sidewalk and a fence next to it is equally important as a Van Gogh or a Brancusi or a Claude Cahun.” Stipe realized he was right, and the sentiment has lingered. “I have no hierarchy between high art, low art, not-art, nature, manmade—they’re all the same to me,” he said. “My early fascination with folk art and what we now call outsider art—to me it was all equal to the greatest paintings or sculptures ever made in the Renaissance.”

For Our Interference Times, Stipe turned to a longtime friend to help find some sort of method of categorization: Douglas Coupland, an artist and writer whose many books include the epochal 1991 novel Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture. Coupland went through some 2,000 photographs that Stipe had taken and grouped them into categories that were alternately impressionistic and clear. On a table in the studio were piles of pictures under Post-it notes bearing taxonomical names like “Social and Personal,” “Objects—Many Cubes,” “Order Emerges,” “Large Icons Emerge!,” “Signal Becomes Noise (Entropy),” “Noise Becomes Signal,” “Digital Patterning,” “Nature Reconquers,” “Architecture Fails—Becomes ‘Other’ Space,” “Architecture Becomes Nothingness,” “Pure Digital,” “Figuration,” “Murk,” and “I Used to Be a Thing Now There’s No Name for Me.”

“I work really well in tandem with other people,” said Stipe, who with R.E.M. was a member of a famously rare breed of band that functioned smoothly and as a collective unit for many years. “I need to have something to bounce off of. I need people to check me or question ‘Why this?’ I’ll give you the answer. It might not be a solid answer, but there’s always a reason. I learned that from Wolfgang Tillmans. There’s never been a picture that he put out for no reason, or just because he likes the light. There’s always a deeper reason. It took me years to arrive at some of them—or I would cheat and ask him. I would say, ‘What’s with all the clothes hanging on bannisters?’ Or, more recently, car headlights? He would tell me and I would be like, ‘Oh fuck, of course!’ Suddenly Wolfgang would open my eyes to a whole work that’s right in front of me.”

Coupland was able to recognize some of Stipe’s curious interests and see others that the artist himself could not. “Doug’s obsessed with my obsession with corners,” Stipe said. “I became obsessed with corners and spent a year photographing them. I couldn’t go anywhere without looking at them and realizing how undervalued they are. We just take them for granted and don’t think about how important they are, but they define the spaces that we think of as comfortable or contained or controlled. Outside of corners is chaos and nature.”

Courtesy Damiani

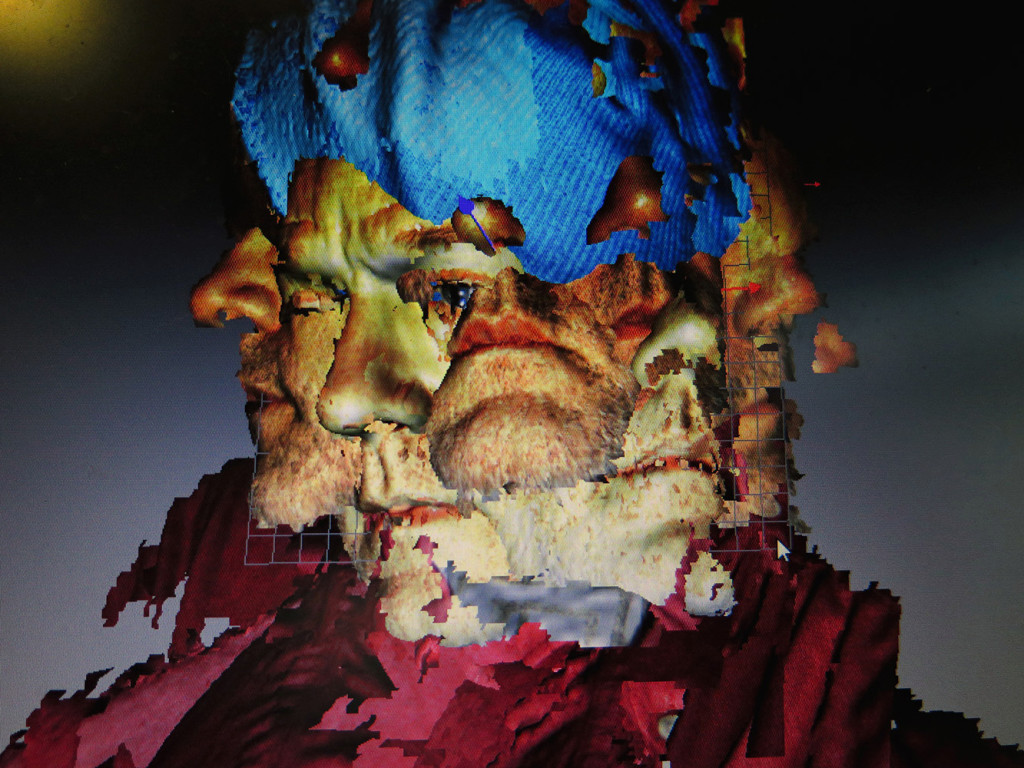

Tension between order and otherwise figures in Our Interference Times, which features lots of images bridging different divides and several subsumed with wavy moiré patterns of the kind that show visual interference that materializes when taking photographs of screens. “In a way, that underpins the analog-versus-digital space we’re in right now,” Stipe said. “It’s an awkward waltz between man and nature, and our attempt to make sense of nature while not realizing that, of course, nature makes a lot more sense than we do. Our clumsy attempt to make sense of something that we read as chaotic—but is in fact not chaotic—is pathetic. That’s where we are in the move from analog to digital—in this miasmic, weird, purgatory-type space where we’re neither fish nor fowl.”

The trajectory is not all downward, though. “I think that digital technology brings us closer to nature,” Stipe said. “Although it seems artificial and cold and inhuman and distant, I think the mirror is going to flip. We’re going to realize how perfect of an organism we are, and how that perfection is something that is not attainable by us. It’s going to take billions and billions of years for us to master something as wonderful as a dragonfly or a cornflower, much less a human being.”

Our Interference Times opens with an inscrutable image on the endpaper at the front: a photo of a window in the studio photocopied repeatedly until it became unrecognizable. “I wanted an abstraction so we went to the Xerox place and Xeroxed and Xeroxed and Xeroxed and Xeroxed—and kept Xeroxing,” Stipe said. “I wanted it to be like the early Television albums, like Marquee Moon [a 1977 album whose cover features a photocopied portrait of the band by Robert Mapplethorpe]. It was the most incredible, exciting thing ever at the time, and it still resonates.” About the image he made as a sort of tribute, he said, “The idea is that you fall into a welcoming window into another world.”

After that is a strange still life that Stipe arranged and photographed in his studio, with a special appearance from a tchotchke he once prized. “It’s a little Hunchback of Notre Dame toy that I carried in my mouth when I was a child,” he said. “I carried him so much that I chewed all the fingers off. I have the original one still, but this is a contemporary replica. I can’t believe someone found this thing from the early 1960s and remade it so that it glows in the dark.”

Courtesy Damiani

One of the most important sections of the book (which isn’t really separated into sections but instead blurs in and out of particular areas of interest) has to do with whales—but first comes a photo of a painting by Paul Nash to introduce the subject. “He was a British artist who came through World War I and had what we would now call post-traumatic stress,” Stipe said of the creator of Winter Sea, from 1925. “This is a painting that, to me, is far beyond what the Cubists were doing. It’s so prescient. It feels contemporary. It feels like Matt Connors.”

Whales enter by way of grainy pictures of the great leviathans breeching and sending mist into the skies above the seas. “Here’s a whale cresting, another whale blowing,” Stipe said of pictures from a spot where he likes to whale-watch in Mexico, near the Sea of Cortez. “Whales come so close to the shore that you can hear them blow.”

Excited by the pictures he took, he began photographing the digital pictures in layers on his computer screen—and started seeing moiré patterns appear. “It’s a digital-digital palimpsest,” he said. “It’s degrading the image, and the reason this became the most important chapter in the book is that these are the shittiest images ever of the most magnificent creature on Earth.”

Courtesy Damiani

“The moiré is a mistake that is easily smoothed out,” Stipe said. “But when we don’t smooth it out, it indicates something different about what we’re looking at and how we’re looking. When you realize what you’re looking at, it becomes this magnificent thing—not a shitty snapshot. We find ourselves now in a world where there are a lot of shitty snapshots.”

Stipe’s thinking on the subject traces back to an artwork he made and has revisited in different fashions: an image of the emoji for a hole in the ground that he printed on the front and back endpapers of a book cover with no pages inside. A photo of it figures in Our Interference Times, and its significance looms large.

Courtesy Damiani

“It marked my change of early adopting of technology,” Stipe said. “It’s a project about using computers and using digital technology wrong—that’s where inspiration lies for me. That’s where god is. It’s in the mistake that you find a way into our unconscious brain, our instinct. And that’s where I think we’re headed, whether we like it or not.”

What interests him most about the hole is that, when he blew it up big enough (“human-size, so that we could fall through it if we needed to”) via halftone printing, the printer said they would need to fix the image, because at that scale it wouldn’t feature clear lines but would render instead as jagged edges. But when Stipe told them to leave it to see how it would appear, “This incredible thing happened,” he said. “You don’t get a halftone and you don’t get pixels. The systems don’t talk to each other, and when you look at it closely, you see neither one nor the other. It’s this weird, wrong, in-between thing—these fucked-up blobs.”

Pointing at the details of the odd printing byproduct in his studio, he continued, admitting to a certain confusion but also affection for the result. “That’s where I think we find ourselves right now,” he said. “That’s what the book is about—we’re the fucked-up blobs.”

[ad_2]

Source link