[ad_1]

From the outside looking in, Arizona’s culture can seem as infertile and impermeable as the soil it is built upon. In 1987, the state’s opposition to a federal holiday honoring Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., led by Gov. Evan Mecham and supported by Sen. John McCain, solidified Arizona as a state plagued by racism in many people’s minds. More recently, that reputation has lived on through laws targeting immigrants and banning ethnic studies in Arizona schools; and the state’s more distant past only compounds the issue.

But like that inhospitable soil, there is a richness beneath a hard, stubborn, superficial layer. In Arizona, there is a vast history of black resistance and self-determination, and at Sunday’s Grammy Awards, 36-year-old folk artist Dom Flemons will put that history on display.

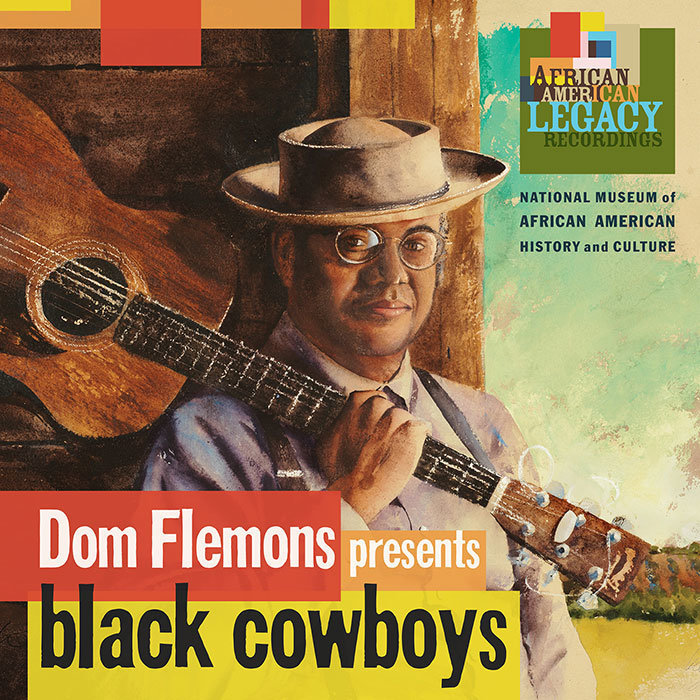

Nominated in the Best Folk Album category, the Arizona native’s critically acclaimed “Black Cowboys” chronicles westward expansion from a black perspective. Ahead of Sunday’s ceremony, HuffPost spoke with Flemons about reclaiming the black folk music tradition, being black in Arizona and searching for a hidden history.

Despite its history, folk music isn’t always considered a genre black people engage with. Why does it resonate with you?

I was always interested in the literature of the songs. I got a degree in English, so I studied up on Chaucer and Shakespeare, and Homeric verse and all that stuff. So the literature always drew me in first.

But also, it’s the sound. I listened to an artist named Clear Rock Platt, for example. He had a rough tone, almost like hard soul or R&B; it was almost like Southern, Dirty South rap in its phraseology compared to the usual cowboy songbook versions that I’d heard from other performers I’d loved too.

At any point did you notice a lack of black representation in the folk genre?

Well, I always sought out artists like Harry Belafonte, Odetta, Lead Belly, Richie Havens, Jackie Washington — who’s a Puerto Rican performer — Taj Mahal, of course. So to me, I never felt like there were zero black performers.

What was it about this specific period and lifestyle that appealed to you? Why “Black Cowboys”?

Well, even though the album is called “Black Cowboys,” the whole purpose is to show that cultural interchange between a bunch of cultures made this very powerful music ― folk music ― that we still revere today. And I thought that being able to show people that there can be multiple stories of Western expansion, that was really appealing to me.

When I was younger, I just kept finding that the black cowboys seemed to vanish into thin air when I looked through a lot of history books. So this album gives people more context about what happened after slavery. This is one of the stories. This is one of the ways you saw people make it.

Were you exposed to the idea of black cowboys as a child?

You know, my dad was big fan of cowboy movies and Westerns when I was growing up, so it was like “Blazing Saddles,” or “Buck and the Preacher” or “Posse” starring Mario Van Peebles. So I’d known about black cowboys in a very peripheral way, but when I read a book called The Negro Cowboys as an adult, that really opened up my ideas of representation of black Western culture.

That idea of black Western culture being represented dovetails nicely into talking about your experience in Arizona. I have my own memories as a black native Arizonan, but we’re all unique. What was your upbringing like?

Growing up in Phoenix, you learn Arizona is a pretty conservative place. But it also has large swaths of more liberal and more progressively minded people throughout the entire state. And part of what really influenced me growing up — in terms of my music — is that I had to use all of the resources that were available to me, and a lot of it was the public library, to look up different musicians from every genre.

So I spent years and years collecting information and burning CDs, and just really enjoying a lot of different types of music.

As you grew older, what did that process of collecting information look like? This album is so rich in history and I imagine you had to do a lot of research in preparation.

Well, one of the things I did for this album was visit the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering in Elko, Nevada. They approached me around the time I started to develop the project, so when I went there, being one of a few black people there, everybody at the event was so excited that I was doing a something about black cowboys. They knew all of these stories, but no one had ever touched this in the way I was doing. So I was given a lot of great information and a lot of great material.

So, it was essentially a collaborative research project.

For sure. But all the history aside, I really tried to make an album that’s nice to listen to. I feel like so much music demands a lot out of the audience, and I wanted to try a different method. I’m not demanding a lot from the audience in their listening experience, but afterward the work demands thinking about the bigger implications and the history conveyed in this record.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

[ad_2]

Source link