Mark Rothko’s Politics: How the Protest-Minded Artist Controlled How His Work Was Seen

For many, Mark Rothko’s transcendent abstractions of fields of intermingling colors often conjure semi-religious states and lofty ideas about death and passing on. Looking at them, one might not know that the artist was a political person, with a strict moral and ethical code that guided how his work was presented. Impressed by Rothko’s commitment to his politics, the collector Dominique de Menil, who commissioned the Abstract Expressionist to make his masterwork, the Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas, once spoke fondly of the artist’s “metaphysical ambitions”—his desire to have his paintings seen in a way that was ethically sound. Below, a look back at four controversies involving how Rothko’s art was shown.

Rothko joins his colleagues in resigning from a prominent arts group (1940)

During the 1930s and ’40s, Rothko regularly expressed himself politically—he was known to call out publications that printed pro-U.S.S.R. articles, and he has been called an “anarchist” by some historians. One of his most notable political gestures of the era was a protest against an advocacy group known as the American Artists’ Congress. Rothko, Adolph Gottlieb, and 15 others came to blows with the Artists’ Congress after it issued a motion in support of the U.S.S.R.’s invasion of Finland, which led to increased hostility in the region. Together, Rothko and his colleagues went on to form the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors, which prized independence above operating as a group.

The “Irascibles” protest a Met exhibition of figurative art (1950)

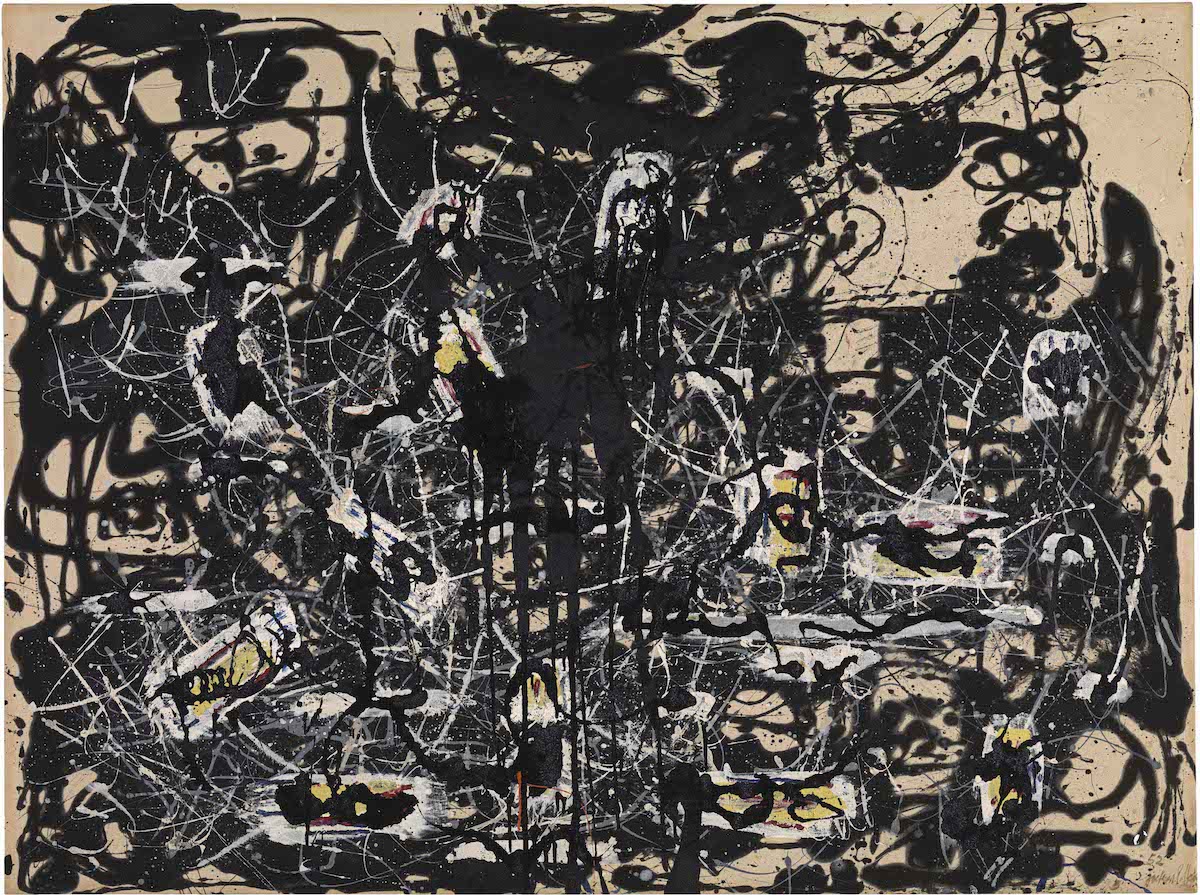

Long before open letters became one of the key forms of communication in the art world, Rothko was one of the 18 signatories of a missive sent to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art that altered the course of the institution’s history. That letter was written in response to a Met show surveying art as it existed in 1950, and it took issue with the exhibition’s emphasis on figuration, which some felt downplayed the significance that abstraction had come to take on in the U.S. Claiming that their “advanced art” was not being shown at the Met, they wrote, “For roughly a hundred years, only advanced art made any consequential contribution to civilization.” Artists such as Rothko, Clyfford Still, Jackson Pollock, Ad Reinhardt, Barnett Newman, Hedda Sterne, and more signed, and they became known as the “Irascibles,” thanks to an iconic Life magazine shoot that helped make them famous.

A Guggenheim prize is returned by Rothko amid a misunderstanding (1958)

In 1956, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation in New York began to give out the Guggenheim International Award, for which painters from various nations were selected to compete in a juried exhibition. Harry F. Guggenheim, then the president of the foundation’s board, called the prize “an important manifestation of international good will.” So when Rothko was selected as the U.S. winner of the $1,000 prize, it should have been cause for celebration. Behind closed doors, however, Rothko raised concerns, saying his dealer Sidney Janis had submitted his works for consideration without his knowledge. According to Rothko biographer James E. B. Breslin, the artist “did not wish to make his refusal into a public gesture.” He quietly mailed the $1,000 back to Guggenheim Museum director James Johnson Sweeney, writing, “I have no desire to embarrass anyone.”

One of Mark Rothko’s Seagram Murals, 1958’s Black on Maroon, on view at Tate Modern in London.

AP Photo/Lefteris Pitarakis

Rothko decries the decadence of the Four Seasons (1959)

In 1958, Mark Rothko was offered his first-ever commission—a series of murals to be placed in New York’s famed Four Seasons restaurant, for which he would have been paid $35,000. Known as the Seagram Murals because they were to appear in the historic Seagram Building, the paintings he created are rendered in dark red tones, with barely visible orangeish forms that appear to hover over dark red backgrounds. Eventually, however, the commission fell through when Rothko and his wife dined at the restaurant and found himself disgusted with the prices of the dishes on offer. “Anybody who will eat that kind of food for those kind of prices will never look at a painting of mine,” he once said. The paintings have since found their admirers: Many of them went to Tate in London, where they are still on view today.

Rothko refuses to show at Documenta (1959)

The second edition of the vaunted Documenta quinquennial in Kassel, Germany, was a significant one for a couple reasons. For one, it included an increased quotient of artists from the United States, in yet another sign that the center of the postwar art world was no longer in Europe. For another, it became a subject over debate over its curatorial thesis—Arnold Bode and Werner Haftmann staunchly suggested that abstraction was paramount in art-making. Alongside it, another small controversy was waged by Rothko, who refused to show at the event, saying that he would not show his art in a country where so many Jewish people had been killed not more than two decades earlier. According to art historian Beatriz Cordero, Rothko, who was Jewish, suggested to the organizers that he could create paintings made in memory of victims of the Holocaust and set them in a chapel, but the project never came to be.

Published at Fri, 25 Sep 2020 17:22:10 +0000