[ad_1]

This past November, two dissident voices of French postwar music were the subject of retrospectives in New York. The resolutely unclassifiable Luc Ferrari (1929–2005) was warmly celebrated in “Stereo Spasms,” a two-night program of performances at Pioneer Works in Brooklyn on November 18–19, while the series “Recherches Filmiques” at Anthology Film Archives (November 21–27) spotlighted his work in cinema, both as a filmmaker and as a composer of scores. Meanwhile, musician Éliane Radigue (b. 1932) has been the subject of “Intermediate States,” an ongoing program organized by Blank Forms in collaboration with Radigue herself. That Radigue and Ferrari should be toasted in parallel is appropriate: while their work took wildly different forms, both figures began their careers in the orbit of musique concrète, or music created by manipulating recorded sound on tape. They separately broke from this blueprint, cultivating practices that have proven radically prescient.

Musique concrète germinated in Paris in the early 1940s, when the French radio engineer Pierre Schaeffer began experimenting with radiophonic and recorded sound. Schaeffer saw in emerging sound technologies the potential for a music rooted in the material aspects of sound, captured in the raw and then meticulously edited. In 1948, he recorded the clatters, clangs, and whistles of a steam engine, and pieced these sounds together in a composition titled Étude aux chemins de fer (Railway Study). Unbeholden to any tonal system, Étude reframed composing as assemblage, anticipating modern sampling practices.

In 1949, Schaeffer found a partner in the younger composer Pierre Henry. Their early experiments were mixed with discs and phonographs, which at the time were cumbersome editing tools. The introduction of magnetic tape made manipulation and recombination easier. In 1951, they established a studio under the name Group de Recherche de Musique Concrète (GRMC), where they approached recorded sounds as discrete objects to be studied rigorously and estranged from recognizable sources through techniques of looping, cutting, and splicing.

Ferrari, who had studied with the composers Olivier Messiaen and Arthur Honegger, was brought into the fold of the GRMC in 1958, around the time Henry acrimoniously split from Schaeffer. Ferrari was to be a part of what Schaeffer deemed a “new era,” renaming the studio the Group de Recherches Musicales (GRM). While Ferrari counted musique concrète among his formative influences, he also nurtured a much wider and more heterogeneous set of interests, including John Cage and Surrealism.

Ferrari eventually found a sonic analogue to the Surrealist objet trouvé in “anecdotal recording,” capturing everyday sound with a Nagra portable tape recorder. With his composition Hétérozygote (1963–64), Ferrari began integrating sonic “anecdotes” into his work. This line of exploration found its apotheosis in Presque rien no. 1 ou le lever du jour au bord de la mer (Almost Nothing No. 1., or Daybreak at Seashore, 1967–70): a twenty-one-minute recording of dawn in a Dalmatian fishing village. It seemed a polemically direct and plainspoken document, a sort of sonic vérité. The composition’s apparent fidelity to the facts of time and place was anathema to the GRM, which preferred its sounds excised and isolated from their original contexts.

“Stereo Spasms” at Pioneer Works celebrated Ferrari the rogue recordist, but also Ferrari the polymath, a composer who frustrated the French musical avant-garde by bucking that label and flirting with cinema, television, and painting. In conversation with musician David Grubbs on the event’s second night, Catherine Marcangeli—the translator of the recently released Luc Ferrari: Complete Works, edited by Ferrari’s collaborator and partner, Brunhild Ferrari—touched on Ferrari’s unbounded approach to media, an impulse that led him to dabble in poetry, produce pieces of investigative journalism, and score films such as Piotr Kamler’s claymation fever dream Chronopolis (1982). The highlight of the evening was a performance of Ferrari’s Tautologos III (1969), a score prescribing the mad repetition of broadly defined gestures (musical and otherwise). Performer Keith Fullerton Whitman periodically got up from the piano to take Polaroids of the proceedings.

In the same spirit as “Stereo Spasms,” “Intermediate States” has highlighted Éliane Radigue’s rather different departure from the world of concrete sounds. Steeped in classical music growing up, Radigue entered the fold of musique concrète in the early ’50s, finding it an enthralling alternative to reigning orthodoxies in composition. She soon sought out Schaeffer and Henry and worked informally with them for several years. After a hiatus from composition, Radigue reunited with Henry in 1967 and acted as his assistant. This new working arrangement quickly dissolved, and in 1968, Radigue began to compose pieces starkly opposed to the concrète paradigm. These early works hinged on the delicate negotiation of feedback generated by a loudspeaker and microphone.

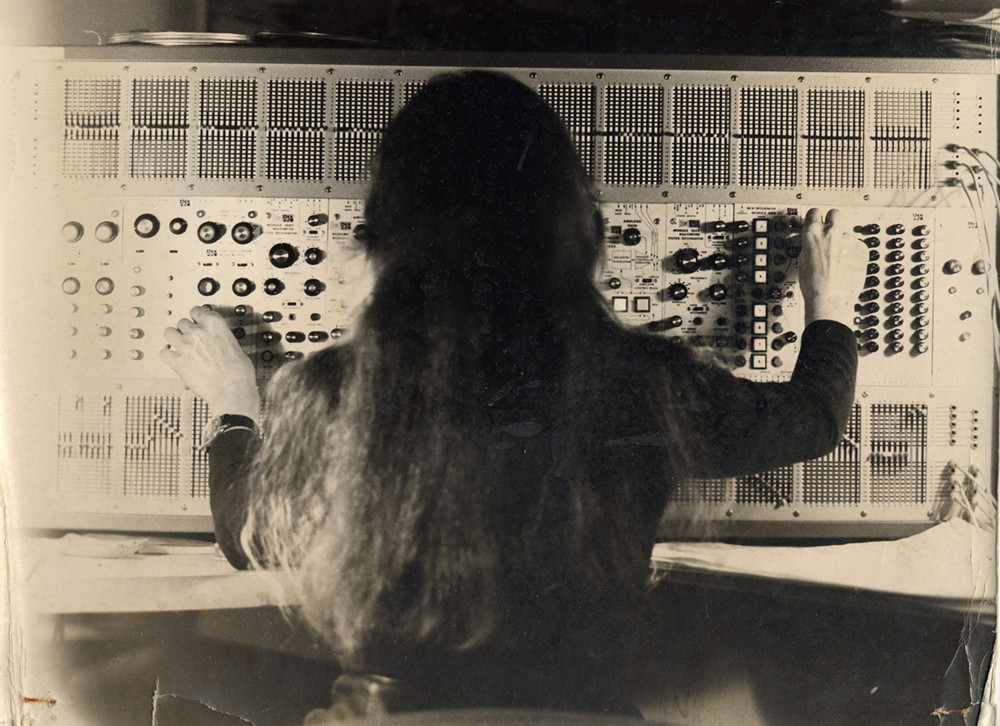

Photo Yves Arman. Courtesy Blank Forms.

In the ’70s, Radigue acquired an ARP 2500 synthesizer, which she would use to create all her major works of the next several decades. With her 70-minute Adnos I (1973–74), the first part of a trilogy, Radigue refined a painstaking working method by which synthesized and processed sounds are recorded to lengths of tape and woven together with the help of careful fades and cross-fades. This rigor was audible in the reel-to-reel presentation of the Adnos trilogy (parts II and III were composed in 1980 and 1982, respectively) at 55 Walker Street on November 16. Running over three hours, the Adnos works traced out a glacial terrain, slowly suffusing the space with subtle, tectonic shifts of rhythm.

Radigue has long harnessed multiple loudspeakers in presentations that distribute her sounds throughout venues, creating dynamic, powerfully embodied listening experiences. She began producing spatialized works—what she termed “sound propositions”—for gallery contexts early in her career, and in 1970, she collaborated with French artist Tania Mouraud on a meditative sculptural environment that hummed at a frequency of 200 Hz. Radigue, often cited as a pillar of drone music, can also be regarded as an early innovator of the sound installation. Her knack for perceptual trickery and her keen ability to charge space are called to mind by recent works like Ryoji Ikeda’s A [continuum], 2018, an installation comprising a semi-circle of five speakers, each tuned to a different historical pitch standard for the musical note A4.

Ferrari’s influence was often legible in his collaborations with younger admirers. In the last decade of his life he took to working with experimental turntablists like erikM and DJ Olive, who introduced him to a new sampler-based practice of musical bricolage that carried echoes of his early musical experiments at GRM. More indirectly, Ferrari’s anecdotal recording and turn to the environmental soundscape in Presque Rien No. 1 predicted a crest of interest, in the ‘60s and ‘70s, in acoustic ecology; in a 1998 interview, Ferrari reflected bitterly on his lack of recognition in this regard. Artists such as Andrea Polli and Jana Winderen have recently brought a polemical edge to this genealogy of soundscape composition, using environmental recording to survey the degradation of natural habitats and the consequences of climate change.

One hopes that the programs surveyed here will encourage listeners to tease still more inspiration from the radical gestures of Radigue and Ferrari. Decades on, they remain capable of troubling boundaries, transporting bodies, and beguiling the ear.

[ad_2]

Source link