[ad_1]

This year marks one hundred years of the famous Bauhaus school, undoubtedly the most influential institution during the interwar period. This particular art education unit was founded by Walter Gropius with the intent to promote an entirely new approach to art and life. The paradigm of modernity was enhanced by a group of distinguished professors and avant-garde pioneers, and one of them was Hungarian artist László Moholy-Nagy.

This outstanding figure was a genuine innovator who managed to break the constraints of any medium spanning from painting to photography and film and experiment to the full extent. To be more precise, Moholy-Nagy was predecessor to later postwar avant-garde movements, a persistent explorer as well as a passionate educator.

Celebrating the Bauhaus anniversary is the Hauser & Wirth show focusing on the Moholy-Nagy works made during the early period from the early 1920s to the 1940s.

The Eclecticism of László Moholy-Nagy

Shortly after the outbreak of World War I in 1918, László Moholy-Nagy was wounded and discharged from the army. Two years later, he moved to Berlin from his native country where his career of an artist/theorist developed. Walter Gropius heard for Moholy-Nagy’s reputation and so he summoned him to start working as a lecturer at the Bauhaus School of Art and Design. In 1928, Moholy-Nagy left the Bauhaus and established his own design studio in Berlin, but due to the rise of Nazism, the artist moved first to the Netherlands, then to London and finally in 1937 to the United States where he worked as a lecturer at The School of Design in Chicago, which was modeled after the Bauhaus school.

The artist was dazzled with new technologies and modern materials, all in accordance with his utopian vision of art and society; Moholy-Nagy was the first interwar artist who embraced latest scientific equipment such as the telescope, microscope, and radiography as tools for making art. His explorations primarily corresponded with the Constructivist theories and he believed that art should be in sync with the present moment and reflect constantly changing technology.

Breaking The Media Borders

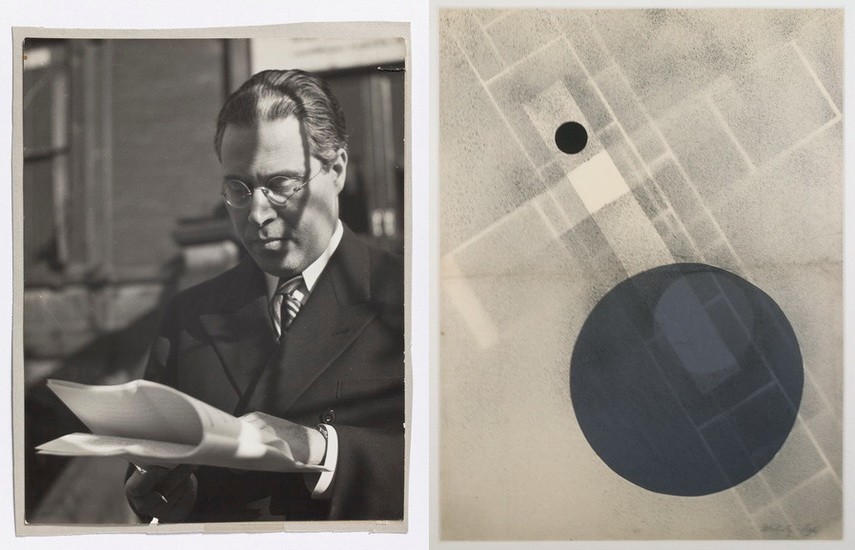

The upcoming exhibition is curated by the artist’s grandson Daniel Hug, whose intention is to underline the crucial impact Moholy-Nagy made on the art history of the 20th century. Namely, his practice cannot be categorized since he constantly shifted between disciplines, but it can be said that photography and film are the most dominant media; the artist was enchanted with the culture of light, a concept thoroughly explored in his extensive writings.

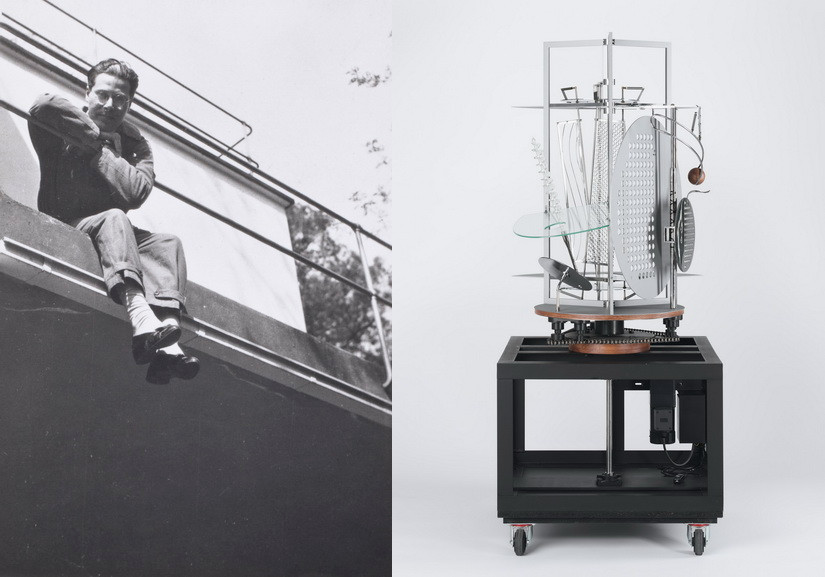

Moholy-Nagy’s interest in optics, light, movement and space-time concepts led him to produce the first kinetic sculpture called Light Prop for an Electric Stage in 1930, a replica of which will be displayed in the exhibition. This peculiar device reflects his experimental approach based on the integration of art and design with science and technology and was used for producing visual effects for a film called Ein Lichtspeiel schwarz weiss grau (A Lightplay black white gray). This film features the machine’s dynamic movement in close-up, and an array of abstract surfaces, reflections, and dramatic shadows.

Alongside these experimental moving paintings, Moholy-Nagy experimented with photography, which was indeed his primary medium of choice. By exploiting the photographic process, he unraveled its formal possibilities and was practically the first to produce the famous photograms or photographs made without the camera (the objects were placed onto photosensitive paper and exposed to light creating unexpected compositions). Moholy-Nagy went even further by photographing the photograms, enlarging them so the distinction between original and a copy becomes fully blurred (such as the work Gyroscope made in between 1925 and 1928 which will be displayed).

After a short while of exploring the domains of technology, in 1930 Moholy-Nagy returned to painting. His later paintings consist of floating and overlapping forms since the artist tested various effects to achieve the impression of depth. A good example is CH Space 6 from 1941 which shows how well Moholy-Nagy expressed his a multidisciplinary approach on canvas as well.

Moholy-Nagy at Hauser & Wirth

It is clear that Moholy-Nagy was not just egoistically focused on changing the role of the artist in regards to technology, but was also concerned how such a shift addresses the society; furthermore, he occupied himself with a question whether art can modify the human perception and the act of seeing (the light effects, superimpositions, accelerated and reversed images). Moholy-Nagy firmly believed that art and design could, and should, cooperate with technology for the betterment of humanity, as well as that art can educate. Once he stated:

Art sharpens one’s senses, one’s view, one’s mind, and one’s observations.

For a complete and through analyzis of László Moholy-Nagy’s practice, we would need more than this brief description of the upcoming exhibition, yet any sort of take on his radical practice contributes to a better understanding how this modernist giant articulated the notion of the future and the role of art in a society.

László Moholy-Nagy will be on display at the Hauser & Wirth London from 22 May until 7 September 2019.

Editors’ Tip: László Moholy-Nagy: Painting, Photography, Film: Bauhausbücher 8

Offered a position at the Weimar Bauhaus in 1923, László Moholy-Nagy (1895–1946) soon belonged to the inner circle of Bauhaus masters. When the school moved to Dessau, Moholy-Nagy and Walter Gropius began a fruitful collaboration as joint publishers of the Bauhausbücher series. In addition to designing and editing the Bauhausbücher, Moholy-Nagy produced a title of his own: the legendary Painting, Photography, Film. In this book, Moholy-Nagy’s efforts to have photography and filmmaking recognized as art forms on the same level as painting are propounded and explained at length. The artist makes the case for a radical rethinking of the visual arts and the further development of photographic design to keep pace with a radically changing technological modernity.

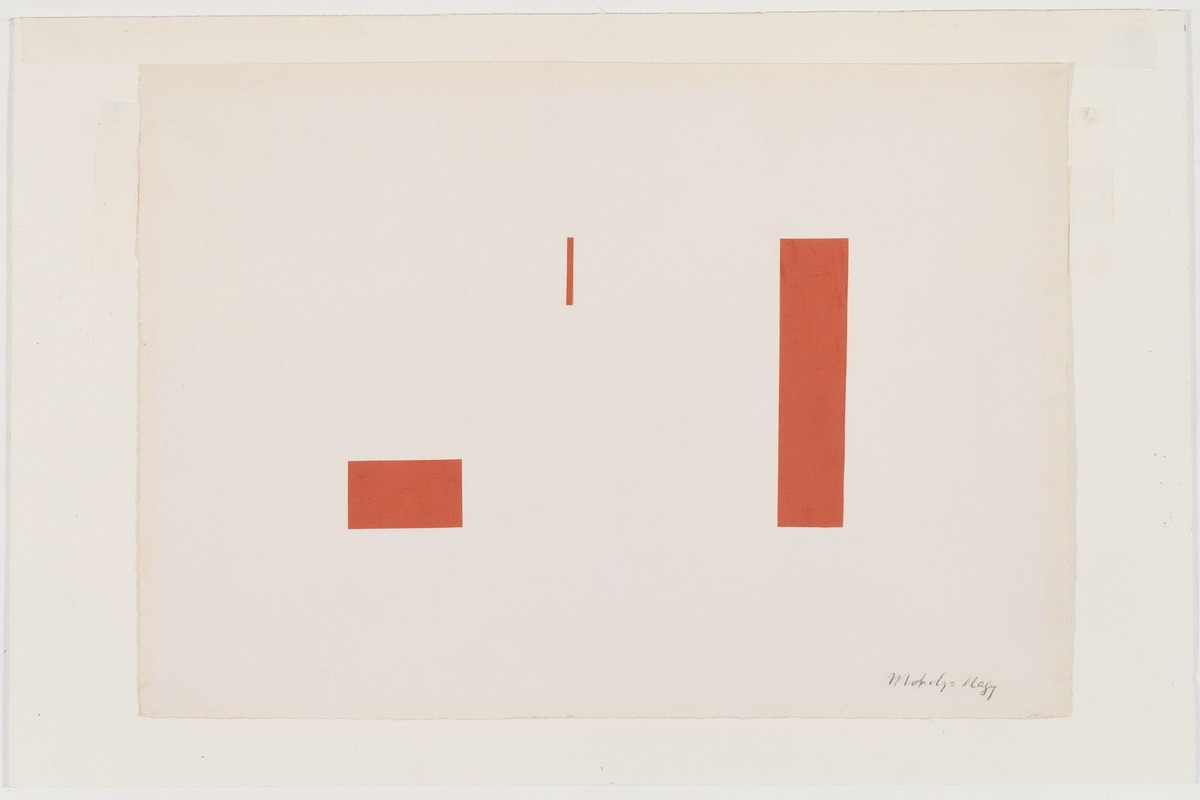

Featured image: László Moholy-Nagy – Red Collage, 1921. Collage on paper, 22 x 33 cm / 8 5/8 x 13 in; Typographic Collage, 1922. Collage on Paper, 27.5 x 38 cm / 10 7/8 x 15 in. Courtesy of the Estate of László Moholy-Nagy © the Estate of László Moholy-Nagy. Courtesy Hauser & Wirth.

[ad_2]

Source link