[ad_1]

Still from Jenn Nkiru’s BLACK TO TECHNO (2019).

© JENN NKIRU

“From another perspective, a cyborg world might be about lived social and bodily realities in which people are not afraid of their joint kinship with animals and machines, not afraid of permanently partial identities and contradictory standpoints.” —Donna J. Haraway, A Cyborg Manifesto, 1984

In March, I saw a solo performance project by the scholar and dancer Anna Martine Whitehead. The performance took place in a large repurposed building in Detroit’s North End neighborhood that was once home to the early 20th-century film collective Jam Handy. It later became a church. In the piece, Notes on Territory, Whitehead danced and lectured on freedom, and lack of freedom, as it pertains to histories of enslaved Africans and their descendants, especially highlighting the narrative of Harriet Jacobs, who spent many years in a confined cell in the home of a relative to evade the possibility of being discovered and thrown back into slavery.

Whitehead remarked on the etymology of factors and factories. Factor is defined as a circumstance, fact, or influence that contributes to a result or outcome. A factory then, is a site where factors reside, labor, or produce—it’s a site of incubation where a factor becomes fungible, or commodified.

At the genesis of modern history, the factory was a prison, or a slave castle on the coast of West Africa, that contained enslaved factors. It was the boat, the barracoon that transported human factors from the continent to the New World where they would be transformed by the factory into an object—less than human.

I left thinking about the lineage of the factory, how it has been sustained through time and how it has influenced Detroit’s making and unmaking. As the Ford era began in the early 20th century, the factory became something else. Black migrants came to be transformed by the factories of Ford and others, from fungible objects into the proletariat.

With an $800 loan from his family, soon-to-be music mogul Berry Gordy started Motown Records in 1957 with the Ford assembly line in mind. Gordy mimicked factory processes, aiming to incubate and transform talents into formidable performers and to avoid becoming a factor in a Ford factory himself.

Such transformation through the contemporary factory has been endlessly romanticized as a means of perpetuating the bootstrap ideology of the American Dream, which says that if you work hard, you will reap the benefits of your labor. Of course, factory work in many places today involves the same fundamental structures of surveillance and enslavement as it did hundreds of years ago.

In 1968 the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement was organized to protest the poor working conditions and racism that proliferated throughout Detroit automobile factories. Divestment by domestic auto companies had begun after the 1967 rebellion and ensuing white flight. Activist and factory worker James Lee Boggs prophesied a “vanishing herd” of the working class, brought on by automation and the disregard for Black laborers by corporations. During the latter half of the 20th century, Boggs argued, human workers would transform from collaborators of auto machines into obsolete factors that would be replaced by them.

At this time of growing tension, a different kind of factory emerged that seemed to arrest the precariousness of that moment, address the continued desire for freedom and escape, and create a site that responded to the hyper development of automation and outsourcing. The new factory would be called Techno, a sonic genre, now 30 years old, that codifies the beauty of analog instinct and binary rhythm.

Filmmaker and writer Jenn Nkiru recently released a “social anthropological” experimental short film entitled BLACK TO TECHNO that animates, as she puts it, the “cosmic archaeology” of Techno and its indirect and direct influence. Nonlinear in form, BLACK TO TECHNO subtly examines factories (actual and conceptual) and their position in modernity, as well as the relationships, involving human bodies, machines, and spirit, that come into being in and because of them.

The 20-minute film begins with the origin myth of the Deep Sea Dwellers created by the Techno group Drexciya, a narrative that coincided with their sonic makings. A voice orates: “Basically there is some sort of underwater country that is inhabited by the unborn children of pregnant women who were thrown off the slave ships during the Middle Passage and drowned.…” Drexciya fans know that the foundation story continues with these unborn children, who continue to breathe through amniotic fluid. As this tale is recalled in the film, large speakers appear with a dark cosmic background as the introduction concludes. What follows is archival footage of Black women working in agricultural spaces during the early 1900s, the maternal factors—former slaves and descendants of slaves—laboring to build out U.S. territory, birthing and breeding more commodities for incubation.

Still from Jenn Nkiru’s BLACK TO TECHNO (2019).

© JENN NKIRU

These sharecropping scenes are intertwined with more recent images of workers laboring in Detroit automobile factories. As archival footage of auto workers in factories from throughout the 20th century is on display, a story is shared by the sound artist Onyx Ashanti about his grandfather, one of many factory workers who named his machine to humanize it. This machine pressed metal all day, but one day, when Ashanti’s grandfather placed his hand in the machine accidentally, it spared his hand—for the first and only time, it refused to press down. The narrative argues that man and machine have the ability to become one in spirit and mind.

The spirit and machine melding to make Techno sound could be said to have origins as early as the 1970s in Southeast Michigan. Around this time, a 13-year-old by the name of Juan Atkins was joyriding around the Detroit suburb of Belleville in his parent’s car. He picked up his comrade Derrick May (also 13) and played a track for him by the Berlin-based electronic group Kraftwerk, which is filled with synthetic sounds that mimic the visual language of a computer device. It was the first time May had ever heard the group, and he would later describe their music as “alien” “stiff white boy funk.” In this same listening session, Atkins played an 8-track with music by Parliament-Funkadelic.

Around this time, the enigmatic DJ Electrifying Mojo, whose identity was long unknown, was digging through discarded tracks at Detroit’s WGPR rock radio station, where he worked. He noticed a great number of Kraftwerk records that had been tossed aside, unused. Curious, he played one, and continued to play alternative funk, electronic, house, and disco during his late-night sets on WGPR. Atkins, May, and later, the Brooklyn-born producer Kevin Saunderson would have their musical interests cultivated by Mojo’s astute ear and incomparable nightly playlist. This sonic serendipity, along with the boys’ unrelenting curiosity, would enable them to produce an electronic sonic of the West called Techno that would form what Nkiru termed an “alien alliance” with Kraftwerk in the East.

Nkiru’s film does not aim to provide a concise linear framework for explaining this origin story of Techno. Instead, she situates the viewer on a couch in a Detroiter’s living room and presents some of what we might have seen or heard on the television and radio in Detroit from the 1970s to the 2000s. One of the voices heard throughout the film is that of Atkins. Archival clips appear from the New Dance Show, Detroit’s first DIY television dance program, which featured host R. J. Watkins and local dancers in a format somewhat like Soul Train. In a video that appears to have been shot with a mobile phone or first-generation camcorder, men in baggy shorts, sweats, Pumas, Reebok sneakers, and throwback jerseys dance in the center of small crowds of more men, carrying out the Detroit Jit (colloquially known in the Midwest as footwork)—a dance that involves a rapid yet ostensibly smooth foot movement that accompanies fast electronic soul music with deep 808s and perhaps a commanding chant like “Let me see yo’ foot work.”

BLACK TO TECHNO presents retro footage of an interview with the anonymous Electrifying Mojo, who is cloaked in shadow as he summons the “Midnight Funk Association” by radio. There are also 1990s shots of Black women in hair salons, as the Detroit-based journalist Imani Mixon recalls a story her mother told her about a hair salon called Betina’s on Michigan Avenue that operated 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, allowing dancers who were leaving popular Techno warehouses like the City Club or Michigan Institute to touch up their “A-symmetrical, bob or fade” hairdos after sweating it out through the night.

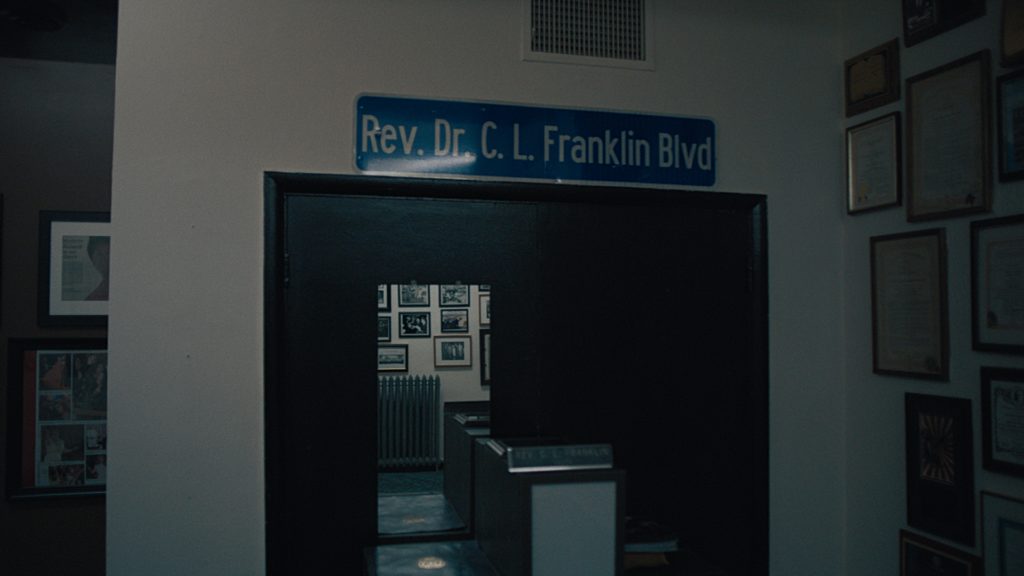

In another series of scenes, Minister Freedom Allah, a young Black male MC and orator appears on-screen as he walks about one of the less gentrified, more residential areas of Detroit, which includes distinctive single-family colonial homes (some occupied, some seemingly abandoned). As he passes a church on the corner with a brick steeple and automobiles parked on dead grass, he describes the city as a mecca for Black creative and spiritual foundation and gestation. Berry Gordy is named, the Honorable Elijah Muhammad is named, Aretha Franklin is named, Black Bottom, the historically Black neighborhood where Southern Black migrants found refuge in the city, is named.

Nkiru captures Freedom Allah from afar and then continuously zooms in on him as he walks about in an overcast Detroit landscape and narrows in on the crux of his sermon. He becomes louder, his voice distinct and raspy. His cadence could be mistaken for a sign of anger if you are unfamiliar with the ways of Black Detroit speech, which is often filled with angst and urgency. The vernacular of this speech is not unlike that of a Baptist preacher. The backdrop to his powerful monologue is the city in ruin—a backdrop that has become a simplistic metaphor for its supposedly deserved demise—and it risks flattening the breadth of the contributions and forms of expressivity that have been made by Black Americans in and from Detroit. Techno is an exemplary accumulation of all these things, but for the viewer, it is important that they do not ingest this image, this narrative, without understanding the full complexity of what is being addressed here.

Nkiru teases out the complex range of influences on Techno by inserting audio scholarship by the DJ and scholar Lynnée Denise, who remarks on the impact of Black ancestral spirituality—specifically baptismal, Black Pentecostalism—on Black Detroiters, and its genesis and development beyond the city, growing out of New Bethel Baptist on the Northwest side.

Still from Jenn Nkiru’s BLACK TO TECHNO (2019).

© JENN NKIRU

New Bethel could also be viewed as a factory, of Black Pentecostal breath, dispossession and repossession, and the revolutionary organizing of factory unions, and as a site where “one learns about Black life as a sacred practice, and the anticipatory drive of Spirit,” as the Black studies and religion scholar Ashon T. Crawley has declared. Reverend C. L. Franklin and his daughter Aretha maintained what Denise has referred to as “the cradle of blues ministry . . .” Blues (being an origin story itself) becomes funk, jazz, hip-hop, and Techno. These forms coexist in a pot of Black expressivity made for sustaining soul, the spirit of Black expression and faith. As the film argues, it is in the Black church where the spirit is nurtured and eventually made to meld with machine.

“This industrialized city lives side by side with machines and robots . . .” —Dream Hampton

BLACK TO TECHNO declares that the machine has enabled and unearthed a sonic expression that could not be discovered otherwise. The machine, according to this film, allows for humans to extend themselves, and thus their expressivity, in ways they have not been able to do in the past.

Here, though, it is essential to recall the factory worker mentioned above, whose entanglement with his friend, the machine, resulted in a relationship that led the machine to spare his hand. The composer and scholar Beth Coleman, who also lends scholarship to the film, explains that this relationship between man and machine is one of “mimesis.” There is a deeply romantic sense to this dynamic, which is often compared to that of beat maker and synthesizer, 808, etc. But we must understand that two very different relationships of power are active here—one between autoworker and machine, the other between music producer and machine. The curious musician has a certain set of freedoms to experiment and produce with a device outside the structure of corporate production, while autoworkers are required to meld with machines (that will later replace them) to generate profits for a commercial body. The melding of human and machine isn’t voluntary in the auto factory. Failing to acknowledge this distinction risks idealizing the capitalist structures that have driven and bound human and machine together in ways that can mute human expressivity instead of free it. Contrarily, when humans court relationships with devices all on their own, we can be left with an indelible beauty of linguistic and sonic collaboration.

In the only scenes in BLACK TO TECHNO that includes footage of DJs performing, we are presented with three women. Identified as “Factory DJs,” DJ Stacey “Hotwaxx” Hale, DJ Minx, and DJ Holographics perform side by side on three turntables in an auto factory in front of imported blue and yellow Fukui-brand machinery. DJ Holographics is an emerging figure in Detroit’s electronic music scene and a self-described “one-woman funk machine.” DJ Minx was a student at the house club Music Institute in Detroit during the 1980s, where she honed her skills. She became a regular disc jockey on WGPR, like Mojo before her, and hosted the electronic music show Deep Space Radio. Hale, deemed the “godmother of house music,” was one of the first women to learn how to transition from one record to the next between two turntables using a mixer. In the ’80s she performed on The Scene (a spinoff of The New Dance Show) and at notable Techno and house venues like the Warehouse and Club Hollywood, where she often played from midnight till 6 a.m. to crowds made up mostly of women. Hale, who identifies as a member of the LGBT community, has described her music practice as aligning with the queerness of her sexuality.

The DJs Frankie Knuckles and Larry Levan shaped the queer house and dance culture of, respectively, Chicago and Detroit. In Detroit, Ken Collier, a Black queer man spinning records at Club Heaven helped make it arguably Detroit’s queer Black center, on Seven Mile and Woodward. Collier mentored Derrick May, Kevin Saunderson, and particularly inspired Hotwaxx’s career after she first saw him perform at Club Chessmate when she was seventeen. While Hotwaxx is a DJ of soulful house, her coming-of-age as a DJ was thoroughly intertwined with the production of Techno, and she was influenced by the same people who laid the foundations for the genre.

Throughout the history of Techno—or at least as I have learned about its origins and development, through archival research and anecdotes—this queer and womanist thread appears only rarely. We know it is there, but it is a narrative that has largely been revealed and celebrated only retroactively (as marginalized stories tend to be). Nkiru attends to the desire for revised, accurate history by making visible three Black womxn DJs who are from various stages in the development of Techno and its surrounding genres, like House, Funk, and EDM.

Still from Jenn Nkiru’s BLACK TO TECHNO (2019).

© JENN NKIRU

We see the Factory DJs—Hale, Minx, and Holographic—as they mix and scratch, moving in synchronized slow-motion over their turntables, but we are not able to hear the sounds that their actions should be creating. As they spin, the iconic Cybotron track “Clear,” composed by members Juan Atkins and Richard Davis, plays, with no aural trace of the DJs. The womxn are maestros and muted at the same time, their sounds overshadowed by those of their male Techno peers and predecessors. The film is making palpable the underground, obscured queer and womxn presence in house and Techno history.

Watching the scene, I longed to hear anecdotes from DJ Hotwaxx about the unarchived moments when she DJed at Club Hollywood to an all-lady crowd in the 1980s, but “Clear” dominates the frame through its undeniable sonic force.

. . .

It is this wall we are going to smash. By using the untapped energy potential of sound we are going to destroy this wall much the same as certain frequencies shatter glass. Techno is a music based in experimentation; it is music for the future of the human race. Without this music there will be no peace, no love, no vision. By simply communicating through sound, techno has brought people of all different nationalities together under one roof to enjoy themselves. Isn’t it obvious that music and dance are the keys to the universe? —Underground Resistance Manifesto, 1992

Toward its latter half, BLACK TO TECHNO focuses on the alignment between Detroit Techno and the warehouse culture of Berlin’s electronic scene, which bubbled up simultaneously in the 1970s and ’80s. The development of electronic music in Berlin preceded the fall of the Wall, and the genre became a soundtrack and score for the country’s reunification. A manifesto written by Underground Resistance (UR)—the Detroit-based Techno collective and record label comprising Mad Mike Banks and Jeff Mills—is recited in Nkiru’s film by the inimitable music producer Waajeed, poet and writer Jessica Care Moore, and UR Detroit DJ and producer John Collins. UR championed, and continues to operate from, a social-justice orientation. Its members are avid interrogators of capitalism, labor (factory) exploitation, and disparities between the haves and have-nots. The scenes that involve their manifesto—in which Moore, Waajeed, and Collins are captured from below as their distinct faces appear to glide through the built environment of the city—elucidate commitments similar to the social-justice efforts of Berlin’s electronic scene. Although the manifesto was imagined in the city of Detroit, it’s clear that it could have been easily adopted by people in Berlin to express their own desires for a new and just world.

Still from Jenn Nkiru’s BLACK TO TECHNO (2019).

© JENN NKIRU

A few years ago, I visited some Detroit friends in Berlin who were on an artist retreat. I went straight from the airport to meet them at a Jamaican restaurant in the Kreuzberg borough that is managed by my friends’ cousin. Afterward, we huddled up in the cousin’s Mini Cooper (after filling ourselves with several cocktails and some of the best jerk chicken I have ever had) and made our way to a club where Derrick May, who’d discovered Kraftwerk at 13 in the ’70s, was set to perform.

While waiting, dancing, and drinking in the club until late, familiar Techno sounds began to fill the room. We made our way closer to the stage, into the sweaty crowd of dancers. I immediately took off layers and layers of clothing I had covered myself with to brave the German chill. Going from outside to inside had felt like stepping into a sauna out of 30-degree weather. As we inched closer to the stage, through a fog of sweat and artificial smoke, the distinctive pulse of the mechanical Techno sound vibration felt like it had possessed my body. I could no longer differentiate between my own pulsating heart and the primal pulse of the music; the music began to breathe for me, and completely muted my own heart pattern. The air was smoky and thick. Each breath I consumed, I seemed to inhale a deeper awareness of the collective panting ethos that surrounded me, a small element melding into a monolith of dancing bodies. Much of the crowd was evidently on some type of drug (as one is supposed to be at raves). Many had their eyes closed, or their eyes were rolling back in their heads, neck exposed, face kissing the air above, and their bodies appeared to be in constant movement—in a series of syncopations. At its height, when one is in the thick of a Techno sermon, when the DJ has peaked at his aural thesis, you are able to witness the spirit of people on the dance floor—a transparency that can be freighting and exhilarating at the same time. It was here, my first time seeing May perform, that I was enlightened to that fact of Techno and how it encourages congregations to shed all performativity, posturing, and masking—to share one’s soul.

Nkiru prioritizes the acknowledgment of spirit in her work, often sourcing imagery that includes opaque movements and sounds that are exclusive to Black faith sacrament. BLACK TO TECHNO can be viewed as an extension of her previous project, Rebirth Is Necessary (2017), another nonlinear moving-image experience that begins with death, or rather the liminal space between living, birth, and rebirth. In it, archival and original footage are also paired. Within the short film’s first two minutes, a Black man with conked hair, gold teeth, and dark rectangular shades from perhaps the 1950s or ’60s declares that “the blues is something that is hard to get acquainted with, it’s just like death.” Death, though, is the beginning in this analysis. Compiling profound footage from throughout the 20th century—Black folks dancing, Black folks in worship, Black folks loving, Black folks in water, Black folks whose bodies have totally submitted to what others might mistake for a possession that needs to be exorcised—Nkiru codifies the necessity of allowing for the death of spirit, in order to obtain control of it, to have agency over oneself, just as the shedding of old, scaled skin welcomes the arrival of vibrant new one. Blackness and the expressions that enable it are accomplished in this perpetual practice of renewal. In BLACK TO TECHNO, Nkiru proposes that Techno music—the offspring of European postmodern computer electric and Southern blues funk that gestated in the Motor City—is a conduit and enabler for such a restorative tradition. It is a ritual that opens up, reveals, and reclaims spirit.

A screening of BLACK TO TECHNO on May 27 at Norwest Gallery in Detroit will be followed by a panel discussion with Jenn Nkiru, Imani Mixon, DJ Stacey “Hotwaxx” Hale, Tracy Washington, and Lynnée Denise, moderated by Taylor Renee Aldridge. The film will also be presented at the Whitney Museum in New York on June 1, as part of the Whitney Biennial.

[ad_2]

Source link