[ad_1]

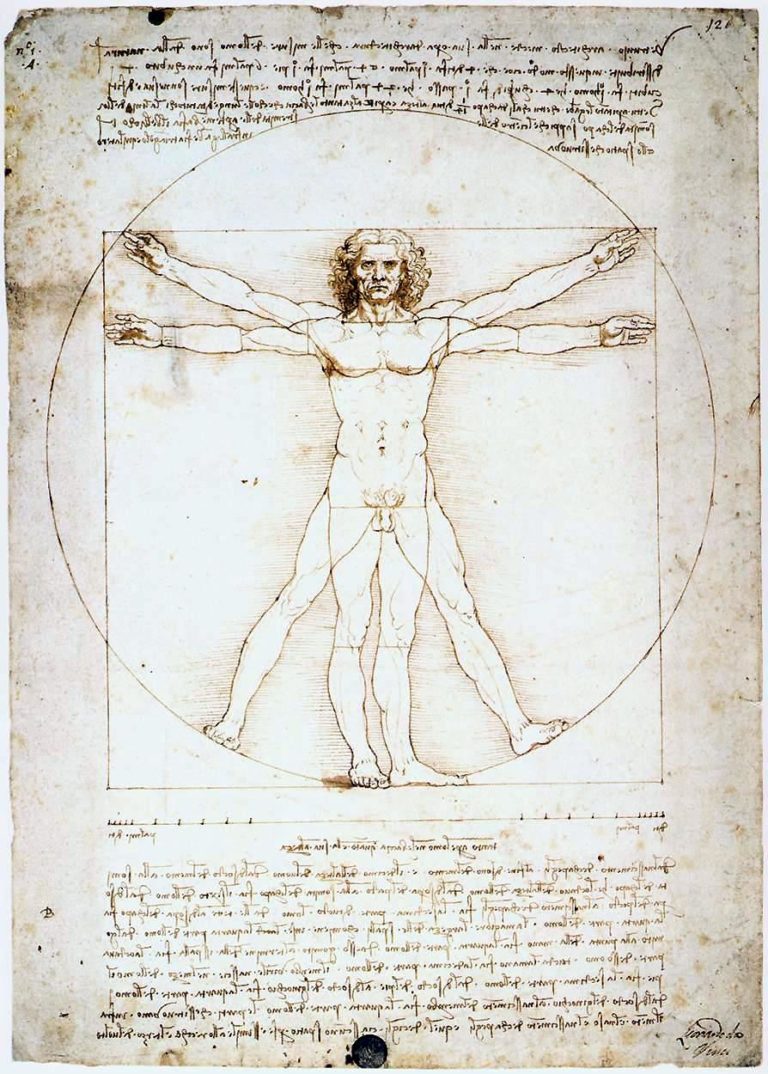

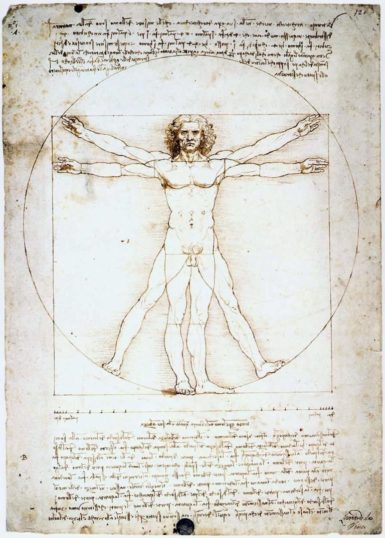

Leonardo da Vinci, Vitruvian Man, ca. 1490.

VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

With just days to go before its hotly anticipated Leonardo da Vinci retrospective opens, the Louvre has finally secured the loan of one of the artist’s key works, following a two-year political battle and skirmishes in the Italian judicial system.

Reversing a lower court’s ruling, an Italian court ruled today that Leonardo’s famed drawing Vitruvian Man (ca. 1490) can travel from the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice to Paris for a blockbuster meant to celebrate the 500th anniversary of the Renaissance artist’s death, which is due to open on October 24. The Italian radio station RTL first reported the news.

Italia Nostra, a group that advocates for the protection of Italian heritage, had previously tried to scuttle the loan, alleging that the drawing was too fragile to travel. After Italia Nostra lobbied to keep the work in Italy, the Tribunale Amministrativo Regionale (TAR) said that the work’s physical state meant that it should only be shown once every six years, which would prohibit it from traveling because it had already been exhibited this past summer in Venice. That decision has been rendered moot by the new ruling, which came from an appellate division of the TAR.

A representative for Italia Nostra did not immediately respond to a request for comment. The Louvre declined to comment.

A diplomatic battle over the Vitruvian Man has been ongoing since 2017, when the Italian culture minister, Dario Franceschini, first called for the loan to be made. His vocal support for the loan was met with opposition from activists and historians, who alleged that the work could be damaged if it traveled and that it should stay in Italy, the country where Leonardo was born. Ultimately, the Gallerie dell’Accademia’s director agreed to send the work in exchange for works by Raphael that the Louvre holds.

The court’s decision is the latest dramatic turn for a show that, since its start, has been plagued with difficulties securing loans, bureaucratic issues, and mystique surrounding the authenticity of what was expected to be one of its star pieces, Salvator Mundi (ca. 1500), which famously set a record for the most expensive work ever sold at auction when it went for $450.3 million at Christie’s in 2017. As of this week, it is still unclear whether that painting will appear at the Louvre—a spokesperson for the museum told the Washington Post that it was “still waiting for an answer” on whether the painting’s owner, which is believed to be Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, would send the work for the show.

[ad_2]

Source link