[ad_1]

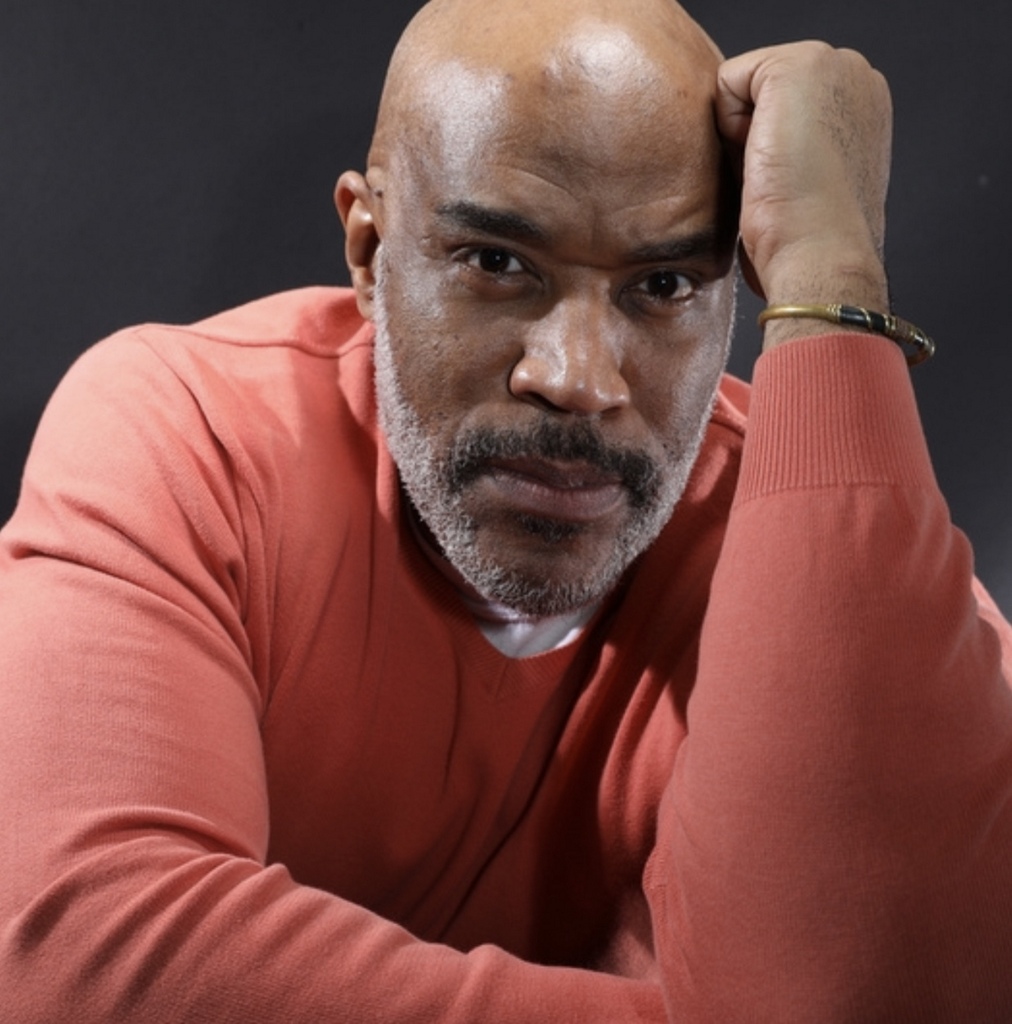

By Sean Yoes, AFRO Baltimore Editor, [email protected]

“I smoke a blunt to take the pain out

If I wasn’t high I’d try to blow my brains out…”

-Tupak Shakur

Since I first entered the doors of the AFRO in January 1989, at the original headquarters on the corner of Druid Hill and Eutaw, I’ve been blessed to work with some of the most talented storytellers in America.

The most talented I’ve ever known by far is Earl Byrd.

A few weeks ago my friend and colleague Diane Hocker, the AFRO’s Director of Community and Public Relations came over to my desk and handed me an original manuscript written by Byrd titled, “Gettin’ High Like I’m Goin Die.”

“I knew you would appreciate this,” Hocker said with a smile.

She knows me well; I revered Byrd and his towering talent.

His essay starts with the quote from Tupak Shakur, which I led with at the top of this column. And although it was not dated, I’m fairly sure Byrd penned it in 1999. How do I know? Because Byrd refers to the age of Liddy Jones, the infamous drug dealer being 57, which Jones would have been in 1999.

If journalism was Byrd’s sanctum sanctorum, surely the underworld of narcotics was his perdition.

“Malik woke up at the morgue on a cold steel slab inside a body bag with a tag tied to his big toe. Paramedics had found him overdosed on heroin near the reservoir in Druid Hill Park and thought he was dead,” Byrd wrote.

“It was a moment of truth, horror, and decision, he tells a room full of recovering and laughing addicts in the basement of his home group Serenity in Sandtown, at Ames Memorial Church at Carey and Baker streets, one of more than 300 Narcotics Anonymous meetings held in Baltimore daily. Thousands of recovering addicts from every strata of society attend these group meetings.”

Byrd knew Malik’s world intimately; he struggled with drug addiction for decades. He died around 2005, but I’m not sure of the exact date. Jake Oliver, the AFRO’s former publisher and CEO (now publisher emeritus), sent Byrd on assignment to Atlantic City. He was sent to explore the burgeoning phenomenon of people flocking to the East Coast gambling capital via ultra-cheap bus rides and tossing their money away. It is unclear whether Byrd actually died in Atlantic City, but Oliver said he is certain he fell ill in the coastal town. And although the circumstances of his death are murky, I believe his decades of narcotics abuse contributed to his ultimate demise.

Oliver told me recently he originally hired Byrd to write for the AFRO in the early 1990’s. He had been highly recommended by reporters at the now defunct daily, The News American, who Byrd wrote for. He allegedly freelanced for the Baltimore Sun as well. The word on Byrd as a storyteller was undisputed.

“They told me (the News American reporters),`This is the best writer you will ever meet,’” Oliver said.

“His use of imagery was something…it was pure poetry.

Oliver is right; Byrd was the embodiment of an extraordinary storyteller. I didn’t meet him until 2004, not long before he died. I had just won a series of awards for my reporting on the 50th anniversary of Brown v. Board, and Byrd would chide me by referring to me as, “You award winner you.” We were definitely competitive, but it was a Brotherly competition.

Ultimately, I was in awe of him; I’m pretty good, but Byrd was great.

I would actually watch him write in our newsroom. He would rhythmically pat his feet when he was in the mix, his muse flowing freely, informing every phrase.

I miss him; I miss his talent, I miss his laughter, I miss his spirit. I miss his stories; nobody did it like Byrd.

“For most addicts like Malik, however, slinging drugs and committing crime did not earn them homes and luxury cars. It supported their habit. And smoking crack-cocaine brought individuals to their knees who otherwise would never have thought of themselves as junkies. Not viewed with the loathing of injecting heroin and cocaine with needles, crack proved to be a nightmare drug that addicted instantly and wrecked middle-class and Wall Street types at the peak of their careers,” Byrd wrote.

“All, for a time, found drug use insurmountable. Babies were born addicted. Families were lost. Friends used. Self-respect denied. The will to overcome destroyed. Tens of thousands were left confined to ghetto poverty, prison, or the cemetery.”

Nobody did it like Earl Byrd.

Sean Yoes is the AFRO’s Baltimore editor and author of, Baltimore After Freddie Gray: Real Stories From One of America’s Great Imperiled Cities.

[ad_2]

Source link