[ad_1]

Denzil Forrester, Velvet Rush, 2018, oil on canvas, 80½ x 107⅝ inches.

MARK BLOWER/©DENZIL FORRESTER/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND STEPHEN FRIEDMAN GALLERY, LONDON

Denzil Forrester ascribes his overdue ascent to the forefront of the British art scene over the past few years to fellow artist Peter Doig. It was as a student at Central Saint Martins in London that Doig first saw the work of the Grenada-born Forrester at his 1983 graduation show at the Royal College of Art, where he earned an MFA. But the two artists would not meet until 2015—after which Doig has since curated shows of Forrester’s work.

The latest sign of Forrester’s heightened visibility was a survey this year at Stephen Friedman Gallery, and a major show is scheduled for Nottingham Contemporary next year, but his work is still housed in only three U.K. institutions: Tate, the Arts Council Collection, and the Harris Museum and Academy in Preston. Meanwhile, the 63-year-old artist’s participation in group and solo exhibitions over the 40 years of his career has been sparse, making the overview provided by the Friedman show essential.

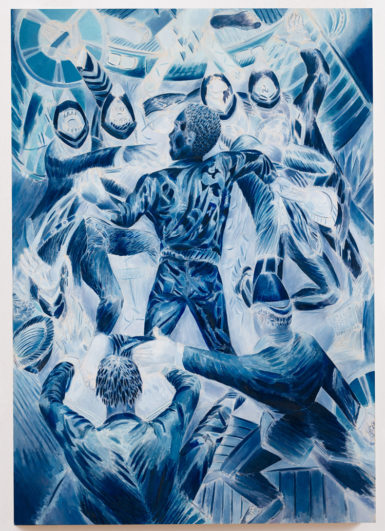

Denzil Forrester, Blue Jay, 1987, oil on canvas, 107¾ x 75⅞ inches.

MARK BLOWER/©DENZIL FORRESTER/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND STEPHEN FRIEDMAN GALLERY, LONDON

The exhibition began with works from the late 1970s and ’80s in London inspired by Jamaican-style sound systems that powered an underground world of unlicensed blues bars, pay-on-the-door nightclubs, and house parties. It was in these spaces—East and North London venues like Phebes, All Nations, and Four Aces—that you could find Forrester at the time, drawing the musical scene of his peers and allowing himself the length of a song, usually no longer than five minutes, to complete a sketch. Later, in his studio, his live-action notes would become oil-on-canvas paintings that were towering but welcoming, with a familiar but hard-to-describe “back-home” spirit.

In more recent works, like Velvet Rush (2018) and Duppy Deh (2018), Forrester depicts such Windrush-era memories in a style deeply shaped by his reverence for certain canonical innovators in the realms of color and shape. As a student, he once said, “We’d literally go to Paris three or four times a year—you’d go see the Monets and come back to your studio. Him and Cézanne made a big impression on me. When I started I was quite Cubistic, but the Cubists got their stuff from Africa anyway. Picasso just took it and ran with it.”

In the communal spaces that Forrester depicts, Black West Indians gyrate in a dub trance, their bodies crouched over and swaying in a dancing style known as skanking. Strobe lights cut through crowds and draw equal attention to elaborate sound equipment of a kind that provides a steady heartbeat of bass. Blended hues of middle-to-dark purple, red, and blue set the tone of the midnight revelers.

Denzil Forrester, Dub Skank, 1979, oil on linen, 60 x 72⅛ inches.

MARK BLOWER/©DENZIL FORRESTER/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND STEPHEN FRIEDMAN GALLERY, LONDON

The sudden death of Forrester’s friend Winston Rose in police custody in 1981 spurred another recurring theme in his work. Forrester has said, “After they killed him they chucked him on the floor of the van and the social worker saw them sitting with their feet on him. I couldn’t stop doing paintings of Winston. They take up all your energy. I didn’t realize how draining they were.” The looming presence of the police appears in many of his pieces, in blue and white exclusively, figured with emphatic gestural strokes. Blue Jay (1989) portrays the faceless policemen with razor-sharp teeth, their mouths wide open, each sporting bobby hats, raging against the crowd with large batons raised above their heads, ready to crash down on unsuspecting partygoers.

With Black Londoners regularly refused entry to pubs and dances in those years, a large portion of the city was closed off. After a tiring, unforgiving week of work, such spaces were vital to West Indian social life—even as they were often regarded by authorities as havens for criminal activity and surveilled and raided without cause. Against such a backdrop, expatriates from different Caribbean countries would synchronize their bodies in dance to soothe the daily weariness from anti-immigrant racial hostility and other hardships. Forrester’s lifework is thus not just a colorful immortalization of ’80s-era London nightlife but also the representation of a burgeoning Windrush generation that was fashioning the styles and sensibilities of Black British culture.

[ad_2]

Source link