[ad_1]

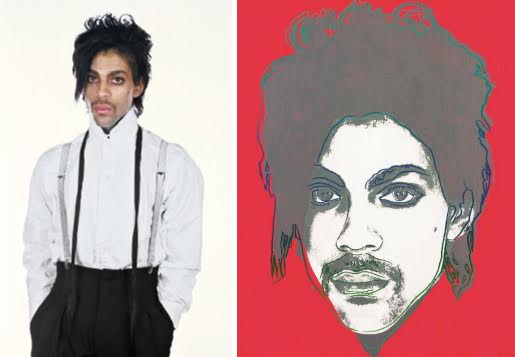

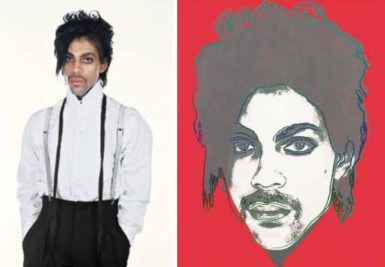

From left to right: Lynn Goldsmith’s portrait of Prince commissioned by Newsweek in 1981; a screenprint from Andy Warhol’s “Prince” series.

In New York’s Southern District Court on Monday, lawyers for the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and photographer Lynn Goldsmith stood before Judge John G. Koeltl in service of their clients in a case taking up a 1984 series of Warhol screenprints of the storied musician Prince.

In a pending case now more than two years old, Goldsmith has alleged that Warhol copied an image she took of Prince in 1981 and, in doing so, violated her copyright. She shot her image of Prince while on assignment for Newsweek, and Warhol used her image for “Prince,” a series of 16 screenprints he made in 1984.

The Warhol Foundation first filed a preemptive motion against Goldsmith’s claim in 2017, alleging then that she was attempting a “shake down.” As the case has continued, the foundation is now demanding a “declaratory judgment” to the effect that Warhol did not infringe upon the photographer’s copyright.

The case takes up complicated issues surrounding art and appropriation. Did Warhol artfully reconstitute Goldsmith’s image, or did he merely copy it? How could one side prove its position either way?

Speaking before the judge on Monday in New York, Luke Nikas, the Warhol Foundation’s attorney from law firm Quinn Emanuel, attempted to address such questions. He said that, however similar they might appear, Warhol and Goldsmith’s representations of Prince serve different purposes. “Andy Warhol took images of people, goods, and companies to force us to confront how we consume them,” Nikas said—adding that, as viewers, “we’re not consuming Prince the person or the icon—we’re consuming the image.”

Nikas suggested that “Goldsmith conveyed no intent to deal with the same topics as Warhol,” adding that their work was made for “entirely different purposes.” The judge concurred, asserting that if one were to put the two prints next to each other, the “common person would point to one and say, ‘Hey, that’s a Warhol!’ So that is its own work of art.”

Lawyers from both sides debated the “protected elements” of Goldsmith’s photograph—formal aspects of it that involved creative choices, such as lighting, color palette, angle, and cropping. Nikas argued that the Warhol work differed from Goldsmith’s photograph in all these respects. Goldsmith’s lawyer, Barry Werbin from Herrick, Feinstein LLP, said another protected element ought to be considered—that Warhol’s work did itself appear in Vanity Fair in 1984, meaning that it, too, could have been made for a magazine. Judge Koeltl disagreed with Werbin’s assertion, noting that the Warhol “Prince” works were art objects originally and not intended for editorial use.

Werbin, on behalf of Goldsmith, maintained that the Warhol screenprint was a “derivative work,” adding, “I think the law’s way of dealing with art and copyright is in flux.”

Both lawyers have asked Judge Koeltl to make a “summary judgment” through which the case would be called off and decided in favor of either the Warhol Foundation or Goldsmith without further arguments. The case is now pending an order from the judge.

[ad_2]

Source link