[ad_1]

Installation view of “New Monuments for New Cities” in Buffalo Bayou Park in Houston.

KATYA HORNER/HIGH LINE NETWORK

Houston is home to 60 or so public monuments—memorial structures, statues, busts, plaques, and other creations that commemorate a person, people, event, or history. At least two of them, according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, explicitly celebrate the Confederacy. And so, in 2017, as political pressure began to succeed in having such statues, as well as street signs and other markers, removed in a number of cities across the country, I began to get excited about the potential for change in Houston, where I live and work, for a reckoning with the at-times disgusting past of the United States. I hoped for a reshaping of public space, with artists, organizers, and activists leading the way, as they so often have. I was thinking of Bree Newsome scaling a 30-foot flagpole to remove the Confederate flag in Columbia, South Carolina, in 2015, and the work of the collective Paper Monuments to research and represent marginalized histories in New Orleans—people fighting for a more inclusive and just America.

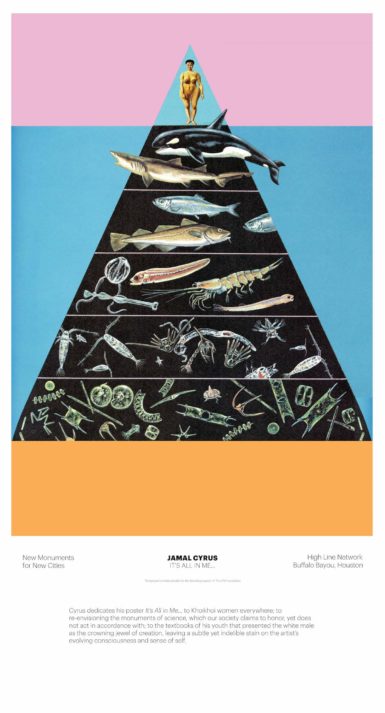

Jamal Cyrus’s proposed monument, It’s All in Me. Click to enlarge.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND HIGH LINE NETWORK

Protests about the monuments occurred in Houston, and I was an eager participant in countless conversations about the issues at stake, but these objects have remained standing. And yet, there has been reason for optimism, in the form of a multifaceted new initiative that could be seen as a kind of compromise, and perhaps a path forward. The High Line Network, a coalition of North American industrial reuse projects started by the leadership of the eponymous elevated railway-turned-public promenade in New York, has initiated “New Monuments for New Cities,” a public art project that asks artists to “imagine a monument for today, for your city, for your community.”

This project is timely, aiming to explore directly what contemporary monuments are now, from the perspective of artists living and working in Houston, Austin, Chicago, Toronto, and New York. A touring initiative, it features 25 artists’ answers in the form of photographs, drawings, and other renderings that will be shown in the aforementioned cities, where the selected artists live and work. Its first stop is Houston, in partnership with Buffalo Bayou Partnership, a nonprofit organization transforming and revitalizing Buffalo Bayou, a 53-mile river running through Houston to the Gulf of Mexico that is the city’s most significant natural resource. The proposals are now emblazoned on standing monuments in the city’s Buffalo Bayou Park, where they will remain through April 30.

Phillip Pyle II’s Broken Obelisk Elbows. Click to enlarge.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND HIGH LINE NETWORK

The participating artists from Houston have made work that is deeply concerned with history, people of color, environmental justice, immigration, and activist histories. Regina Agu’s Expanding Monuments is an inverted photo-collage that appears to depict the relationship between nature and the development of new buildings with scaffolding exteriors under construction. Expanding Monuments pushes back against the ubiquitous form of monument dedicated to a single, all-encompassing historical narrative or person, and asks, in an accompanying text, “What if new monuments were marked by movement through space and time, and by the continued reimagining of collective relationships to moments, sites and people we choose to honor?”

Meanwhile, Jamal Cyrus’s monument, It’s All in Me, is a revision of the scientific monument of the evolutionary pyramid, which replaces the Caucasian male (typically atop the pyramid) with an illustration of Saartje Baartman, a South African woman imprisoned and placed on exhibition at European carnivals in the 19th century. A commentary on hundreds of years of racism in science, it is also a potent picturing of our current moment, in which we see the power of women resisting oppressive treatment and staking out space in new places.

Broken Obelisk Elbows takes its title from the iconic Broken Obelisk (1963–67) sculpture by Barnett Newman that now sits in front of the Rothko Chapel in Houston, dedicated to Martin Luther King, Jr. (That dedication from the patrons John and Dominique de Menil led the city council to reject their attempted donation in the late 1960s.) Phillip Pyle II has updated it in his work by adding golden elbows—aka “swangas,” the wire rims common to the wheels of the Cadillac El Dorados and Caprices that are central to Houston’s slab—car—culture.

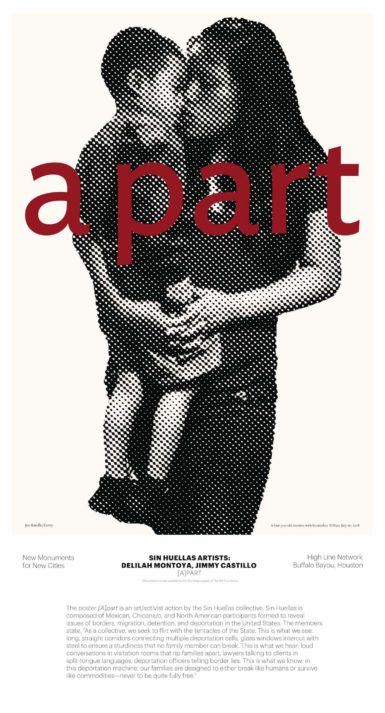

Delilah Montoya and Jimmy Castillo, collectively known as Sin Huellas, display a mother and child kissing, with the words [A]PART overlaid on the image. The image speaks to the horrible moment of families being ripped apart by the current U.S. administration’s tactics along the U.S.–Mexico border, which uphold white supremacy.

Historically speaking, Houston has had a bad habit of failing to preserve its local culture. Countering that, Nick Vaughn and Jake Margolin have honored the gay bar Mary’s Naturally, a hub for the city’s queer community for 40 years, in their work. An image taken from a 1976 poster stands in place of the absent plaques, busts, or obelisks that the artists believe should commemorate the Houstonians who have died of AIDS-related causes.

Other participating artists in “New Monuments” include Nicole Awai, Daniela Cavazos Midrigal, Teruko Nimura, Rachel Alex Crist, Denise Prince, Vincent Valdez, Eric G. Garcia, Tonika Johnson, Chris Pappan, Richard Santiago (TIAGO), Zissou Tasseff-Elenkoff, Susan Blight, Coco Guzman, Life of a Craphead (Amy Lam and Jon McCurley), An Te Liu, Quentin VerCetty, Judith Bernstein, the Guerrilla Girls, Hans Haacke, Paul Ramirez Jonas, and Xaviera Simmons. All these artists speak to one another in important and magical ways that are specific to their respective cities but expand to have generative conversations about what is happening in real time.

In place of tearing down objectionable monuments, as if the histories they represent never existed, these proposals offer an even more productive opportunity to question and complicate the narratives that we have been spoon-fed for so long, so that new truths can emerge. They allow people to explore the past, understanding that it is not written in stone—and neither are our futures.

Ryan Dennis is curator and art programs director at Project Row Houses in Houston.

[ad_2]

Source link