[ad_1]

Hundreds of FOMO-driven attendees were still on the Bahamian island of Great Exuma, grappling with the reality that the first annual “luxury” Fyre Festival was an unthinkable scam, when California-based laywer Ben Meiselas of Geragos & Geragos began receiving call after call … after call.

The civil rights, class action and litigation firm, which has filed notable consumer lawsuits against companies like EOS lip balm and CenturyLink, had quickly become the priority speed dial for rich, white 20-somethings stranded in the Caribbean with no way home.

“We got calls from people who were looking for lawyers to get off the island ― people who we had known in Los Angeles and people who just knew us from Googling the firm,” Meiselas told HuffPost following the premiere of Hulu’s “Fyre Fraud” documentary, and just days before Netflix’s “Fyre: The Greatest Party That Never Happened” hit the streaming network. Meiselas appears in both films.

“We started getting calls from literally everybody on the island who wanted to be involved in the case,” he said. “I think you can say hell has no wrath like a millennial scorned.”

It was April 27, 2017, and Meiselas and his team were receiving real-time updates from attendees of the first and final day of the most infamous failed music festival in history, created by New York entrepreneur-turned-fraudster Billy McFarland and his Fyre Media minions, including rapper Ja Rule. Fyre Festival was supposed to be a “transformative, immersive” experience on a private island once owned by Pablo Escobar, an event focused on A-list guests, opulent accommodations, Michelin-status food and top-of-their-game musical acts.

What both documentaries make clear is that the festival was, in actuality, a dumpster fire that engulfed guests as soon as they arrived via a chartered plane from Miami to a dusty construction lot filled with rain-soaked FEMA tents and sad cheese sandwiches ― no villas or yacht parties with Kendall Jenner in sight.

After the deluge of phone calls, Geragos & Geragos prepared a $100 million class-action lawsuit and filed it before the weekend was over. The litigation is ongoing.

“The lawsuit itself went as viral as the tweets in terms of bringing light to what was taking place,” Meiselas said. “Then, we started getting the whistleblower information that it was financially fraud, as well.”

McFarland didn’t just scam the Fyre Festival participants; he allegedly defrauded investors and employees out of millions of dollars, too. Now, the nearly unbelievable story of a huckster who hawked his way into the pockets of the rich and not-so-rich is being told in not one but two competing documentaries, both of which have captured the attention of the internet, bringing the grotesque carnival of horrors that was Fyre back into public conversation.

Hulu’s “Fyre Fraud” is more of a true-crime comedy that details the overwhelming influence of social media on human behavior. Netflix’s “Fyre,” on the other hand, is preoccupied with the festival’s inner-workings, as told by McFarland’s scorned Fyre Media employees, Bahamian workers and festival attendees. Both have their faults ― Hulu reportedly paid McFarland an undisclosed amount of money to appear in an exclusive interview; Netflix sugarcoats Fyre Festival promoter Jerry Media’s sketchy involvement in its project as a producer ― but they land on a similar conclusion: McFarland’s heist saga serves as a handy allegory for everything wrong with power and influence in a post-truth era.

Below, Meiselas shares his take on the dueling films and gives an update on the class-action lawsuit.

Hulu/Twitter

How is the litigation going?

Litigations like this take their course. One of the things that you deal with is lawyers making a living doing their own Fyre Festivals ― trying to piggyback on other lawyers or file the exact same lawsuits. So that means all of the lawsuits were all consolidated in New York where we were appointed the lead counsel of the case. We’ve been litigating the case with the three primary defendants — being Grant Margolin [Fyre Festival’s Chief Marketing Officer], Ja Rule [a celebrity partner] and Billy.

The fact that they claimed bankruptcy slowed it down, the fact that there was a criminal investigation slowed it down, but Ja Rule and Grant have filed pre-trial motions basically saying that they didn’t do anything wrong and we pushed back and said they did, so we’re just waiting on some rulings from the judge.

How many clients are in your lawsuit?

It’s probably close to 1,000. I say that without complete precision because in the class action, one or two people represent everybody who was there. But in terms of people on our spreadsheet who called the firm and reached out, I can say there are 1,000 people who call consistently and ask for updates.

Say I spent thousands of dollars to fly to the Bahamas for a luxury music festival, only to arrive in a Lord of the Flies situation. Knowing Billy is a scammer, and has absolutely no money left to his name, how do you even go about getting myself and fellow attendees refunds, let alone damages?

You look at it the same way as any Ponzi scheme case. Think about Bernie Madoff, MedCap, WorldCom, any of these major frauds, they all take different shapes and sizes. But a Ponzi scheme is a Ponzi scheme; people just think of different creative ways to do it. Usually the person who’s primarily responsible doesn’t have money because they ran out of money, which is why they got caught. They’re usually a total fraud to begin with. So what you look at is the ecosystem around them to see which others possibly aided and abetted the fraud as well, and who facilitated the misconduct.

So, in the case, we investigate where there is money and who knew about this, who aided it, who assisted it. Some of those are questions that are remedied by a class action attorney, some of those are questions that are remedied by a bankruptcy trustee. The lawyers who get appointed by the court have authority to conduct investigations, to ask questions and to find where there may be people who assisted this, and if that assistance reaches a certain level of law that provides a cognizable recovery, then the class gets money. A lot of times in these Ponzi scheme cases you investigate banks, lenders, other professionals ― everybody who may have had a role.

Does that include all the investors behind Billy and Fyre Fest?

You know, it could. And I’m somewhat intentionally coy with you because that’s part of a work-product investigation that I’m doing. But generally the answer would be if there was a party ― whoever that third party was, who knew, who fueled it, who went along with the fraud and allowed it to happen ― yeah. There’s always a potential for that party to be responsible in something like this.

Through our litigation and through this societal upheaval and the general disgust [audiences have] when they watch these movies, we see who these people are and just how ridiculous their fraud was.

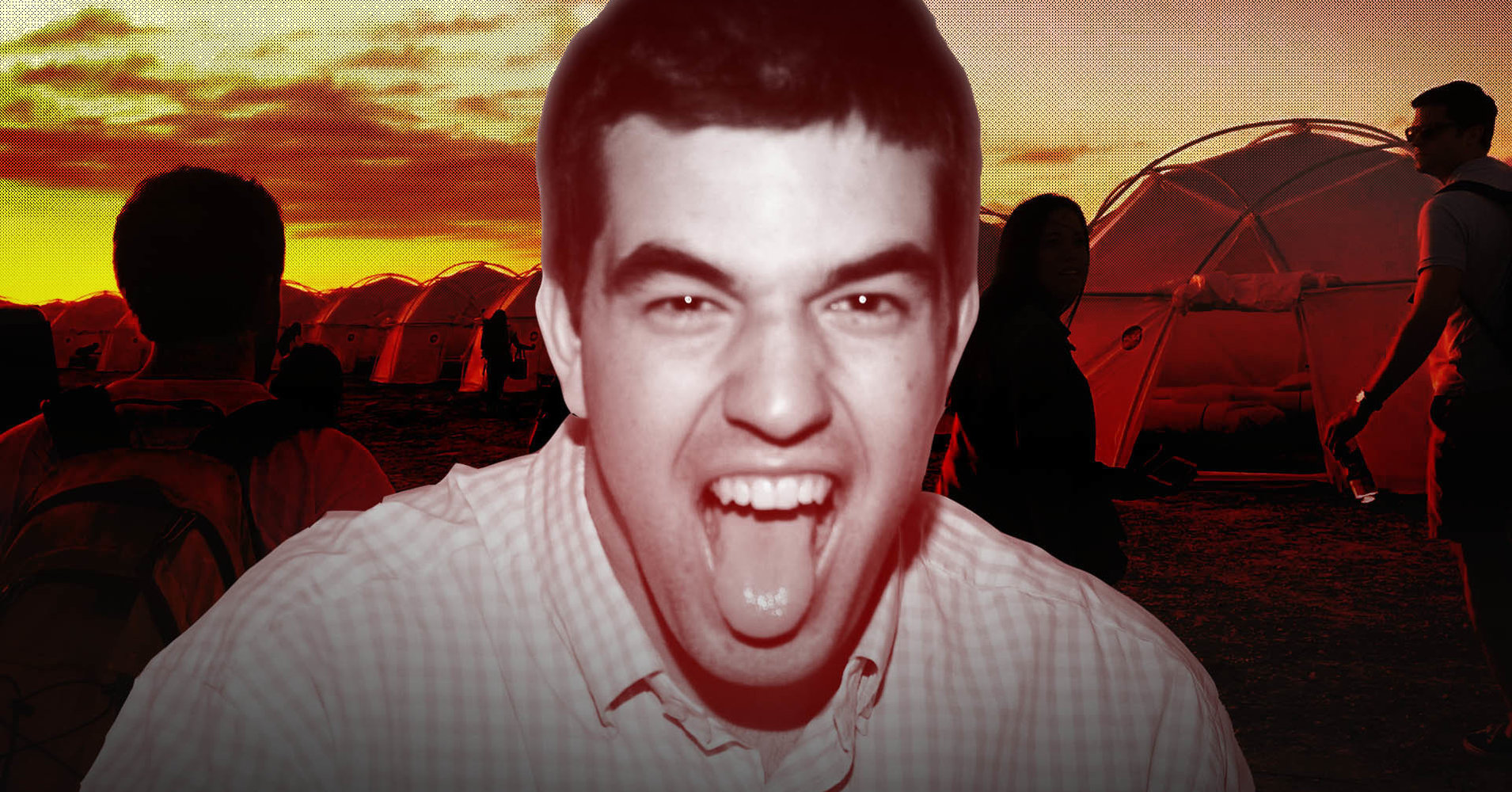

Ben Meiselas

Now, Billy is in prison for six years. But could Ja Rule and Grant face prison time, too?

One, because I’m a civil lawyer, I can’t comment on the criminal proceedings. But I don’t know. I know in my civil case, what I do is to hold them accountable monetarily … I genuinely believe that as a result of [our] litigation and the way it was prosecuted ultimately led to the financial fraud being uncovered* and really changed the whole entertainment industry and festival industry.

[*Editor’s Note: After Geragos & Geragos filed the class-action lawsuit in May 2017, Ben Meiselas says whistleblowers made many aware of the multiple financial fraud schemes Billy McFarland orchestrated to maintain his own wealth. The FBI got involved and authorities discovered that he provided false documents that inflated Fyre Media Inc. revenue by millions. (The company earned less than $60,000). He also altered a Facebook stock-ownership statement to make it appear that he owned shares worth $2.56 million when they were actually valued at $1,499. McFarland is now serving prison time for deceiving his investors, customers and employees.]

Speaking of criminal proceedings, Billy was out on bail but still scamming people for money with fake tickets to things like The Masters, Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show and the Met Gala.

He’s still using the same list from Fyre Festival to try to steal from the same people. The Hulu documentary did such a really, really good job laying it out from all angles and connecting it to the broader zeitgeist. I’m biased but one of my favorite quotes [from the documentary] is: “We have the Fyre Festival going on in the West Wing every day.”

Through our litigation and through this societal upheaval and the general disgust [audiences have] when they watch these movies, we see who these people are and just how ridiculous their fraud was.

There are currently two competing documentaries about the Fyre Fest, and you happen to be in both of them. How were you approached to be a part of Netflix’s and Hulu’s versions, respectively?

I got emails from both of them [Laughs], saying, “Do you want to be in my documentary?” And I was like, “Yeah, sure. I’d be happy to talk about it.” Literally anybody who writes to me about it I talk to, and I say the same thing that I say to you, word for word: there are certain things you can’t talk about with an attorney because it’s an attorney-client privilege but I generally gave a good overview of the case.

I did two separate interviews, one with the first film company I did in California and then with Hulu in New York. They both filmed me for around the same time, although I haven’t seen the Netflix one so I don’t know my role in that or how frequently I’m in it.

You come in toward the end when they get into the blowback after the fest with Billy. Speaking of Billy, apparently Hulu paid him to be a part of their film but Netflix refused to. Still, Netflix’s film is produced by Jerry Media, who did social media for Fyre Festival.

I shouldn’t be asking you the questions, but when you watched the [Netflix] one, did it look more friendly to Billy and Jerry?

Netflix

It’s more insider-y. Jerry Media and Fyre employees talk about how Billy tricked them into thinking they were a part of something amazing. These employees say they believed in him, so they were scammed in a way, too. Yet, they did all stick with it until the end, even though they knew it was going to be a shitstorm.

Yeah [Laughs]. There’s no doubt about that … I went on a network in Chicago and I forget what her name was but she is the voice of Chicago, as she calls herself, and she said, “You millennials are stupid!” She was like, “Pablo Escobar?! You want to go to the island of a drug dealer?” That was her point to me and I said, “I disagree, I’m suing them. I didn’t do the marketing, I didn’t go there!”

But some of your clients are the people who fell for it.

Well … there’s the quote from me [in the Hulu doc], “It would be hilarious and perplexing if it wasn’t criminal, and it’s criminal but it’s still perplexing but it’s still a little bit hilarious.” I do have a sense of humor about this. I’m not one of these stuck-up lawyers who thinks I’m litigating a major Supreme Court precedent. But I think, at the end of the day, it’s a significant and substantial cultural case to be a part of.

I think there were major health implications, as well. It took a turn from being a little bit of schadenfreude, oh-shucks funny to really bad when they trapped people on the island. People were getting physically sick. There could’ve been lots of deaths and injuries. I mean, you see in the Hulu doc these cliffs… it could’ve been really, really, really, really horrible. And then they were sending cease and desist letters to people who were just trying to get off the island, for tweeting “Help.” That’s where, to me, it became a serious case and something that made me really sympathize with these clients who are true victims.

It’s every parents’ worst nightmare to have kids in that age range go and be stranded on an island and not know how to leave. That’s how I think of the different viewpoints: here you have millennial rich kids stuck on an island but at the same time, they were defrauded. This whole thing was a fraud from the onset.

Were any of your clients approached to be interviewed for the documentaries? And would they have had to reach out to you about it?

I’m trying to think if they were. I don’t remember if they were or weren’t, but they wouldn’t need my permission. No one who made the cut on Hulu I recognize to be a client of mine.

Truly, what do you think about these dueling documentaries?

I’m getting a lot of text messages and a lot of emails, and to some extent I’m becoming a meme on Twitter. I mean, look, in many ways the lawsuit that we did and the event really created this cultural moment. What the documentaries are doing is hopefully making people a little more wary of what they’re seeing on social media, to not necessarily buy into this influencer culture and to really pause. We need to relook and rethink, in many ways, how we view advertising and what standards there are. Fyre Festival got caught for a lot of reasons — particularly because they let the people go to the Bahamas ― and Billy’s such a narcissist and an idiot that it blew up in this epic, horrible fashion. But there are many Fyre Festivals going on every day. We as a firm can’t litigate every one of them. We have to pick and choose our battles.

What do these documentaries and the Fyre Festival in general say about the millennial generation and our fixation with social media? Are millennials as a whole gullible?

Yes, is the direct answer. But we’ve always been gullible. It’s just our laws and regulations and ability to detect and increase our gullibility radar changes generationally. We’re dealing, now, with different forces, different forums, different variations, different power triggers of influence. I think, in many ways, that’s being investigated separately by an independent counsel and has been subject to indictment, when you think about fake Twitter accounts and the power of tweets and bots and certain algorithms to advertise to you.

People are gullible because — and I can be an eternal optimist — they all have the urge to be happy and to do good and to want to smile and to want to feel protected in a day-to-day world where that’s not always out there. You turn on the TV every day and then there’s a horrible story: there’s a suicide bomb in Syria, the president is serving Big Macs and Wendy’s to Clemson and it’s depressing. And so people want to get out and do other things! We look at things that make us feel safe and happy, and when that is delivered to us in aggressive ways that have been perfected by social scientists … it hits us, it affects us. People want to have a good time.

Hopefully, as we evolve as a culture, we start being wary of these ads the same way we became wary of Joe Camel. We can see past it and for what it is. People selling snake oil have always been around and people purchasing it have always been around, it’s just new forms, new manifestations, and we just have to see it.

The social media influencers who promoted Fyre Festival scammed people but they were also scammed themselves. So what do you think, are they an enemy in this or victims?

There’s probably a middle ground. I don’t think they’re the enemy. I think that they thought they were promoting something that may have been on brand. But it’s incumbent on them to ask tough questions either before they take that paycheck or before they agree to attach their name behind something. You always hear those stories that a trained boxers’ fists are basically lethal weapons. To some extent, an influencer’s influence is a strength to their professional life. But when they know that they have become walking billboards and they’ve taken on that role every day on social media, they have a higher responsibility to at the very least ask questions. “What am I putting my name behind? Is this product safe?” Because very frequently these products are being sold precisely because of their influence, so it’s hard to totally divorce yourself from it and take no responsibility.

Although, Fyre Festival was really at the time where influence was being perfected as a whole cottage industry.

Are any of your clients suing the celebrities who may have tricked them on social media to attend the Fyre Festival?

That’s not the subject of our case at this time. What you’d have to really see is, is it a gross recklessness there? Ultimately all those issues will be subject of discovery and subject of investigation, which we’ll get to. In terms of the elements, if they were genuine victims and defrauded then that’s not the case. But if, in fact, they knew or should’ve known and facilitated and engineered, then there could be liability there.

50 Cent was probably early money on Ja Rule. 50 Cent warned us of Ja Rule back in 2003.

Ben Meiselas

The Netflix documentary focuses a little more on the Bahamian workers of the Fyre Festival and how they were impacted by the madness that ensued. Do you have any connection to any of those people in the Bahamas?

No. If I could represent them, I would. I can’t because they live in a different country, but if I had a Bahamian legal license I would be happy to represent them all against Billy and everybody who committed the fraud because they’re also very much the victims. Probably the most deeply impacted victims. It just reeks of an exploitative mindset to go in there and really trample on their culture and their well-being, their happiness and their tourism industry. It became such an embarrassment for the Bahamas and for the Exumas and these people who have a great deal of pride. There’s a lot of great tourism there and they’re associated with this thing they never should’ve been associated with. So yeah, if I had a Bahama law license, I’d be happy to represent them.

How long do you think this class-action case will last before you come to a settlement?

A resolution like this in federalist court probably has at least a year or two of litigations.

In the Hulu doc they bring up that Dave Chappelle clip where he pokes fun at Ja Rule. So Ben, have you been able to find Ja Rule and make sense of all this?

Yeah, Ja Rule’s been represented by a number of different lawyers in the case. No, look, he’s filed his motion saying that he didn’t do anything and then you watch these documentaries and you’re like, “C’mon, man.”

50 Cent was probably early money on Ja Rule. 50 Cent warned us of Ja Rule back in 2003.

Hulu’s “Fyre Fraud” is now streaming. Netflix’s “Fyre” hits the platform Friday.

[ad_2]

Source link