[ad_1]

The New Red Order (NRO)’s room-sized installation, Never Settle, 2019, is the 2019 Toronto Biennial’s masterwork. The work skewers the ways in which the concerns of indigenous people are often treated as a topic du jour and co-opted by non-indigenous people.

TONI HAFKENSCHEID/COURTESY TORONTO BIENNIAL OF ART 2019

There’s an adage in the art world that the best way to see a city is to go to a biennial there. There’s a certain logic to that. Traveling around a city between a biennial’s various venues allows you to see it in a new light. Or at least that’s how it felt when I traveled to Toronto for the opening of the inaugural Toronto Biennial of Art a few weeks ago. I’d visited the city twice before, but it wasn’t until this trip that I noticed just how developed it is, particularly around the Gardiner Expressway, an elevated highway that separates the majority of the city from the shores of Lake Ontario. The Biennial’s senior curator, Candice Hopkins, is fond of saying that Toronto is “a city with its back to the water,” and as I drove past high-rise after high-rise her words rang true.

This separation of the city’s current residents from what was its historical life source—a body of fresh water home to an enormous diversity of fish—gave Hopkins her title, “The Shoreline Dilemma.” Her interest in how the city came to be this way drove her to look at the histories of its inhabitants, from the indigenous peoples who first called the land around Lake Ontario home to the waves of colonizers and immigrants who made Toronto one of the world’s most diverse cities. In a short essay for the festival, Hopkins and her co-curator, Tairone Bastien, write that “shorelines resist conventional mapping” and “evade attempts at quantification.” They define the shoreline dilemma as “the breakdown of scientific conventions in the face of nature’s complexities.” How, Hopkins and Bastien ask, can art intercede in this breakdown? The works on view aren’t as much an answer to that question as they are an attempt to look at what and who has been lost in humanity’s quest to create civilizations.

[See images from around the 2019 Toronto Biennial of Art.]

The first thing to know about the Toronto Biennial is that it asks a lot of you as a viewer. The second thing to know is that it is well worth the effort. Take Luis Jacob’s The View from Here (Library), an installation of about a dozen vitrines containing a collection of books, pamphlets, brochures, and other ephemera related to the history of Toronto that Jacob has accumulated over the past several years. (Jacob moved to Canada from Lima, Peru, as a child.) An artist’s collection of such things, of how a city sees itself, can tell us much more than one assembled by historians. And in the Biennial’s most public-facing work, an installation in Toronto’s main transportation hub, Union Station, Jacob has installed several temporary walls that display historical maps of Toronto alongside his own recent photographs of various locations around the city.

Luis Jacob’s The View From Here (Library), 2019, is a collection of printed materials, published since 1872, relating to Toronto, installation view, at the 2019 Toronto Biennial of Art.

TONI HAFKENSCHEID/COURTESY THE TORONTO BIENNIAL OF ART 2019

All that map-reading pays off. I had seen Lou Sheppard’s Dawn Chorus/Evensong a few hours before making my way to Union Station to see Jacob’s work. The piece is a simple sound installation: eight speakers attached to looming wooden poles in the Toronto Sculpture Garden, a small outdoor space along a major thoroughfare in the heart of the historic core of Old Toronto. I spent about a half hour in the square trying to hear the work, billed as an interpretation of birdsong from the Lake Ontario shores. The bustle of Toronto—cars and light-rail trains, people passing through the garden as if it were just another alleyway, the tolling of bells from a nearby church—made it nearly impossible. But in brief moments of quiet when I could make out the sound, the park became incredibly serene. It wasn’t until later, that, pouring over Jacob’s maps, I realized that this park at one point in Toronto’s history had been only a few blocks from the shoreline.

In lieu of a big catalogue, the Biennial offers a guidebook that opens with a land acknowledgment stating, “We acknowledge, first and foremost, that all of these spaces are located on land that has been a site of human activity for more than 12,000 years. This land is the traditional territory of the Huron-Wendat, Haudenosaunee, and Anishinaabe peoples, including the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation. Their stories, belief, and concepts about the land and the water continue to guide and inspire us.” The guidebook provides brief histories of each of the Biennial’s 10 venues and four partner sites that add a dimension to the art displayed in them. The Biennial’s main site at 259 Lake Shore Boulevard East, for instance, was first home to a chemical company that produced formaldehyde, among other things. It was built as urban infill.

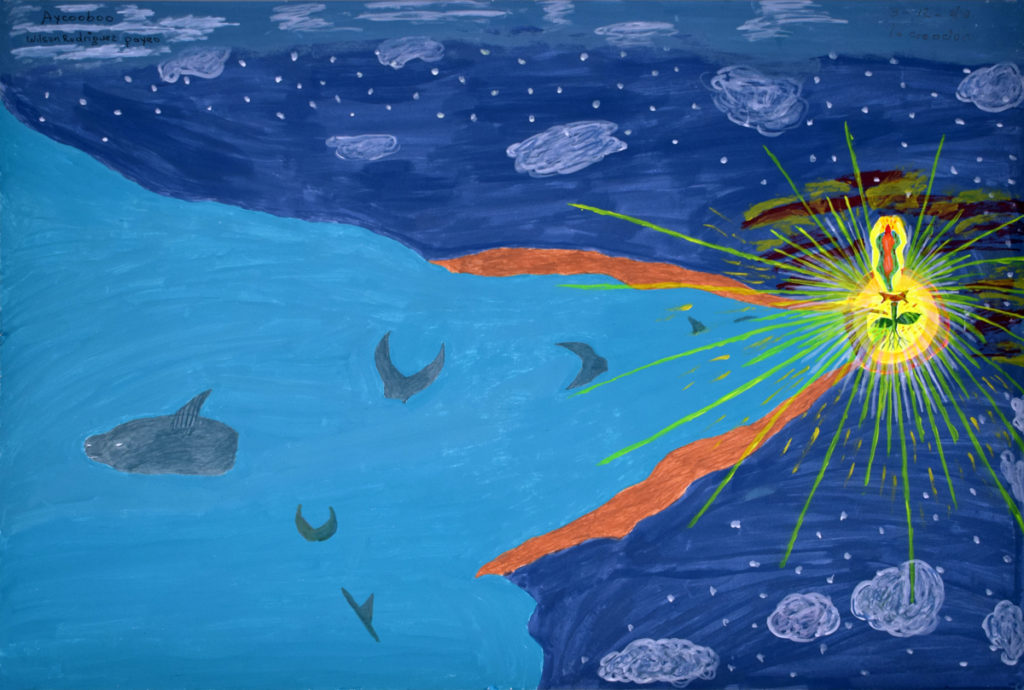

Wilson Rodríguez, La creación, 2018, acrylic on paper.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND INSTITUTO DE VISIÓN, BOGOTÁ

Then there are the Biennial’s educational programs, a major component of the exhibition. I participated in a “Storytelling Tour” on the second public day at the Small Arms Inspection Building, the Biennial’s second main venue in Mississauga, a suburb of Toronto. Our guide took us outside the building to collect an object from nature—a leaf, a stick—and then sat us in front of drawings by Abel Rodríguez; an elder of the Nonuya people of Colombia, he depicts his people’s ancestral lands from memory, as they were displaced in the 1990s by armed conflict in the country. We were asked to draw and describe the object we had selected, and we then walked across the room to sit in front of the work of Wilson Rodríguez, Abel’s son, who makes his own drawings based on the knowledge that Abel passed on to him. Our guide asked, “How do we connect to those who come before us?”

Then again, the Biennial’s masterwork, the piece that will stay with me, needed no explanation. It is a room-size installation, titled Never Settle, by The New Red Order, a collective formed by Adam Khalil and Zack Khalil (both Ojibway) and Jackson Polys (Tlingit). The collective very much tongue-in-cheek-ily bills itself as a “public secret society” that aims to recruit people to explore the ways in which nonindigenous people crave authentic indigeneity in their lives. The room is shaded by red-tinted windows with flashy quotes like “FEEL AT HOME HERE,” “WHAT ARE SAVAGES FOR?,” and “WHERE WILL YOU GO NEXT?”

A brief recruitment video and a longer initiation video contain testimonials from recruited members; the artists are skewering the ways in which the concerns of indigenous people are often treated as a topic du jour and co-opted by nonindigenous people to signal virtue, to feel better about themselves. A copy of an exhibition catalogue from Jimmie Durham’s recent traveling retrospective makes an appearance. Choice lines include: “No one told me I was supposed to care” and “I know it’s not about me … but for me, it is” and “I don’t even feel guilt anymore.”

AA Bronson, far right, delivers his A Public Apology to Siksika Nation. The work was a collaboration with Adrian Stimson (Blackfoot), seated in the audience at center wearing a traditional Siksika headdress.

TRIPLE THREAT/COURTESY TORONTO BIENNIAL OF ART 2019

The Toronto Biennial opened with an apology. The first public day saw AA Bronson, a Berlin-based Canadian artist best known for co-founding, and 25-year collaboration with, the groundbreaking AIDS activist art collective General Idea, deliver a performance artwork A Public Apology to Siksika Nation; the piece detailed his family history and its devastating role in colonizing the Siksika Nation, going back to his great-grandfather, Reverend John William Tims, an “Anglican missionary who did his best to destroy Siksika culture” by establishing a residential school named Old Sun Industrial School. Canada as a whole has recently reckoned with and apologized for the residential school system, which for decades separated indigenous children from their parents in an attempt to Westernize the children by converting them to Christianity and forbidding them to speak their native languages—and often made them the victims of emotional, mental, physical, or sexual abuse. Bronson’s apology might have been overly sentimental if he hadn’t ended it with a stark truth: “I have no apology for genocide: / my words make no difference.”

Bronson’s piece came out of a collaboration with artist Adrian Stimson (Siksika), great-grandson of Old Sun, a legendary Siksika chief whom Tims considered his archenemy. Stimson has created an installation piece that includes a table elegantly set for 10, each plate bearing small sculptures of the bison that were hunted to extinction by colonizers as a way to destroy indigenous peoples’ main food supply. Nearby, he has installed portraits of some 60 of the students who attended Old Sun. The archenemies’ descendants have come together to heal.

Maria Thereza Alves’s mirror sculpture Phantom Pain is installed in Riverdale Park, where the Don River ran before it was straightened. Players of a softball game earlier in the day had stepped over it numerous times.

MAXIMILÍANO DURÓN/ARTNEWS

What has been lost can be hard to find, Maria Thereza Alves seems to tell us in her contributions to the Biennial. For a new commission, Alves, who has been a water-rights activist since her teens, when she testified before a United Nations commission in 1979, has installed a small reflective sculpture in the ground at Riverdale Park, to mark where the nearby Don River once flowed. In the 1880s, like other cities around the world, Toronto straightened the Don, which was prone to heavy flooding. I spent more than two hours looking for Alves’s small sculpture before I saw part of it glinting in the sunlight, the other part having been occluded by the sandy footprints of baseball players. It can be easy, Alves seems to be saying, to walk about oblivious to history.

A similar exploration of what has been lost comes in Susan Schuppli’s feature-length video Learning from Ice, the result of years of research into the preservation of ice cores, cylinders of ice that serve as gauges of climate change. Some of the glaciers from which they’ve been extracted no longer exist. Displayed in the entryway to the Ryerson Image Centre, Syrus Marcus Ware’s eight-channel video Ancestors Can You Read Us? (Dispatches from the Future) presents a message from a future generation living in the year 2072: “Can you read us? We have a message for you.” Earth’s future inhabitants tell us they have survived the climate crisis because of the actions we took, and that we gave them a message to send back in time to us: “We want to warn you … to act, to rebel, to take this Earth back from the capitalists … to find self-determination and freedom. Black people survived because of you.”

Installation view of Syrus Marcus Ware’s multi-channel Ancestors, Can You Read Us? (Dispatches from the Future), 2019, offers a message from 2072.

LARISSA ISSLER/COURTESY RYERSON IMAGE CENTRE

In three short videos, the Jumblies Theatre & Arts, in a project led by artist Ange Loft, present reenactments of broken treaties, most notably the so-called Toronto Purchase of 1787, for which the Mississauga of the Credit were essentially deceived into ceding their lands. They interpreted the 2,000 gun flints, 24 brass kettles, 120 mirrors, 24 laced hats, a bale of flowered flannel, and 96 gallons of rum they received as a gift, not as payment. The group has re-created these objects as sculptures wrapped in fabric and placed next to the video monitors. In one of the videos, an indigenous character poses a hypothetical: “You have a house, and a neighbor moves in. The neighbor kicks you out at a certain point. But it’s still your house and you’ll always believe it’s your house. Right?”

During its planning stages, the Biennial commissioned Loft to create a document called the Toronto Indigenous Context Brief that charts 1,000 years of activity along the waterfront. From that Brief, the curators drew out one essential question that they posed to the participating artists and now pose to exhibition visitors: What does it mean to be in relation? To each other, to those who came before us and will come after us, for those who have been here for generations and those just arriving. After watching the videos, visitors are invited to contribute to the installation by writing down their own thoughts on how best to draw up a treaty.

Jumblies Theatre & Arts with Ange Loft’s installation Talking Treaties, 2019, presents the objects that British gave to the Mississauga of the Credit to buy their ancestral lands in the so-called Toronto Purchase. The Mississauga understood it as simply a gift, not a payment.

TONI HAFKENSCHEID/COURTESY TORONTO BIENNIAL OF ART 2019

Migration patterns are also key to this Biennial. Two videos look at what happens to people in diaspora. Bárbara Wagner and Benjamin de Burca’s RISE is a collaboration with a group of poets, rappers, and musicians in Toronto called Reaching Intelligent Souls Everywhere (R.I.S.E.) made of mostly young people who are first- and second-generation Caribbean in Canada. One woman sings about how, when she introduces herself, she intentionally mispronounces her name because she’s embarrassed to say it properly. It’s not a name that is smooth on the Anglo tongue, she tells us.

In Arin Rungjang’s Ravisara, six Thai women who are all recent immigrants to Berlin enter and exit the various screens at the Harbourfront Centre. They often look pained and wistful; a screen nearby relates their stories and what brought them to Germany. At points the women interact with each other and hold each other and then leave, until only one is left. They mourn together and in private. They share similar stories and yet neither of them can ever fully understand the depths of the other’s sorrow.

A still from Arin Rungjang’s multi-channel video installation Ravisara, 2019, in which Thai immigrants to Berlin comfort each other briefly before leaving. COURTESY THE ARTIST

In a mechanical installation made with recycled aluminum soda and beer cans, Fernando Palma Rodríguez mimics the migratory patterns of monarch butterflies, the only species that travels every year from Canada through the United States to Mexico. No one butterfly ever successfully completes the full cycle of this migration. Those that leave Canada never make it back—but the next generation knows how to get there and start the journey all over again.

As it happened, I didn’t get to see the Guatemala-based Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa’s commissioned piece—a sculptural work that looked at the history of silleros, chairs used in colonial Guatemala to transport explorers and settlers on the backs of the region’s indigenous peoples. It was held up in customs.

[ad_2]

Source link