[ad_1]

Faith Ringgold, The Flag is Bleeding #2 (American Collection #6), 1997.

COURTESY PIPPY HOULDSWORTH GALLERY, LONDON/© 2018 FAITH RINGGOLD/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK

In 1990, Verso Press republished Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman—a now-notorious critique of the 1960s-era Black Power Movement by Michele Wallace, a feminist writer and also the daughter of artist Faith Ringgold—with a new introduction in which the author reflected on lessons learned in the years after her book’s original publication in 1978. “It is my conviction that the only way to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past is to openly discuss them,” Wallace wrote. “Whether in nations, families, or individuals, the practice of being on speaking terms with your past lives is the only thing that makes it possible to trust yourself or anyone else. … The thing that still remained to be worked out was my relationship to my family as a writer and as a woman.”

Stunned when Black Macho first came out by the assertions of her daughter, Ringgold felt the need to respond. In 1980, she wrote a sharp missive quoting passages from the book and addressing them so plainly that one could mistake it for a private family conversation accidentally shared with strangers. But she didn’t make it public—until 2015, when at the age of 85 she published it as a book, A Letter to My Daughter, Michele Wallace, “as a way of confirming and protecting my legacy of a Black woman, mother, and artist in America.”

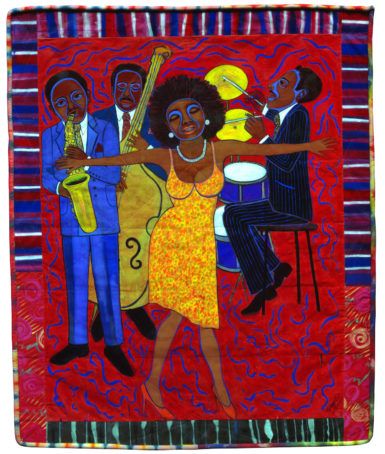

Faith Ringgold, Jazz Stories: Mama Can Sing, Papa Can Blow #1: Somebody Stole My Broken Heart, 2004.

© 2018 FAITH RINGGOLD/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/COURTESY ACA GALLERIES, NEW YORK

Part of that legacy is on display in Ringgold’s current show at Serpentine Galleries in London—her first solo exhibition for a European institution, on view through September 8. Her five decades of artistry are surveyed chronologically and presented in groups of series in which the creative and intellectual context of the Harlem Renaissance (Ringgold was born in Harlem, in 1930) is evident. In rooms that have been crowded with tourists, student groups, and other silently contemplative guests are works like lustrous and detailed story-quilts (among them Jazz Stories: Mama Can Sing, Papa Can Blow #1: Somebody Stole My Broken Heart) from a lineage that Ringgold learned from her mother and grandmother, both former enslaved Africans in Florida.

Also on display are political posters made during the height of the Black Power movement, including one advocating to free activist Angela Davis (America Free Angela, 1971) and another (The People’s Flag Show, 1971) commemorating a protest that Ringgold helped organize at Judson Memorial Church in New York with 100 works conjuring the American flag to challenge laws that restricted the use and display of the flag as a symbol. (Ringgold and two other artists were arrested as a consequence and became known as the Judson Three.)

In 1972, Faith began a series of “tanka” works involving unstretched canvas bordered by strips of cloth stitched with quotes from various Black feminist luminaries. Three are included in the exhibition—including Tanka #18: Mr Black Man Watch Your Step (1973/1993), which cites Jamaican journalist and activist Amy Jacques Garvey, the second wife of Marcus Garvey, from 1925: “Mr Black man, watch your step! Ethiopia’s queens will reign again, and her Amazons protect her shores and people. Strengthen your shaking knees, and move forward or we will displace you and lead on to victory and to glory.”

Faith Ringgold, American People #15: Hide Little Children, 1966.

COURTESY PIPPY HOULDSWORTH GALLERY, LONDON/© 2018 FAITH RINGGOLD/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK

In the Serpentine’s North Gallery I saw for the first time a trifecta of large oil-on-canvas works: portraits of Ringgold and her daughters Michele and Barbara as young adults made as part of her “Slave Rape” series. Ringgold had previously depicted her daughters in her work as children—around the time they attended an experimental integrated school called New Lincoln, which was located on the borders of Spanish Harlem, West Harlem and Central Park North, where the barren setting doubled as a playground for children of different ages and ethnicities to congregate. In American People #15: Hide Little Children (1966), two brown-skinned faces poke out from behind trees with three white ones, seeming either to be innocently playing games or, more sinisterly, seeking refuge from inequalities that even small children are not sheltered from.

Installation view of Faith Ringgold’s “Slave Rape” paintings at Serpentine Galleries.

©2019 FAITH RINGGOLD

By the 1960s, Ringgold’s devotion to addressing the socio-political position of Black women in America made her an unabashed feminist, and her “Slave Rape” paintings show nude Black women against backdrops of green, orange, and red leaves in the forests of Africa. Their wide almond-shaped eyes are startled as their bodies angle toward a viewer—or would-be capturer. If caught, such women were fated to be sold onto ships and sailed to the New World, where they were required to submit to white owners who would frequently exercise their “right of property.”

Barbara is represented in Fear Will Make You Weak, Michele in Run You Might Get Away, and Ringgold herself in Fight to Save Your Life, all from 1972. Each title evokes actions and reactions to the threat of captivity—fright, flight, fight—as well as histories of sexual, gender, and racial oppression that hold up distorted mirrors through which we Black women view ourselves and each other. The power of Ringgold asserting herself and her daughters into such a narrative of resistance cannot be underestimated. Leaving the Serpentine show after a recent visit, I sat with a verse from Gwendolyn Brooks’s poem To Black Women: “Sisters, where there is no hallelujahs, no handshakes, no smiling faces. It has been a hard trudge.”

[ad_2]

Source link