[ad_1]

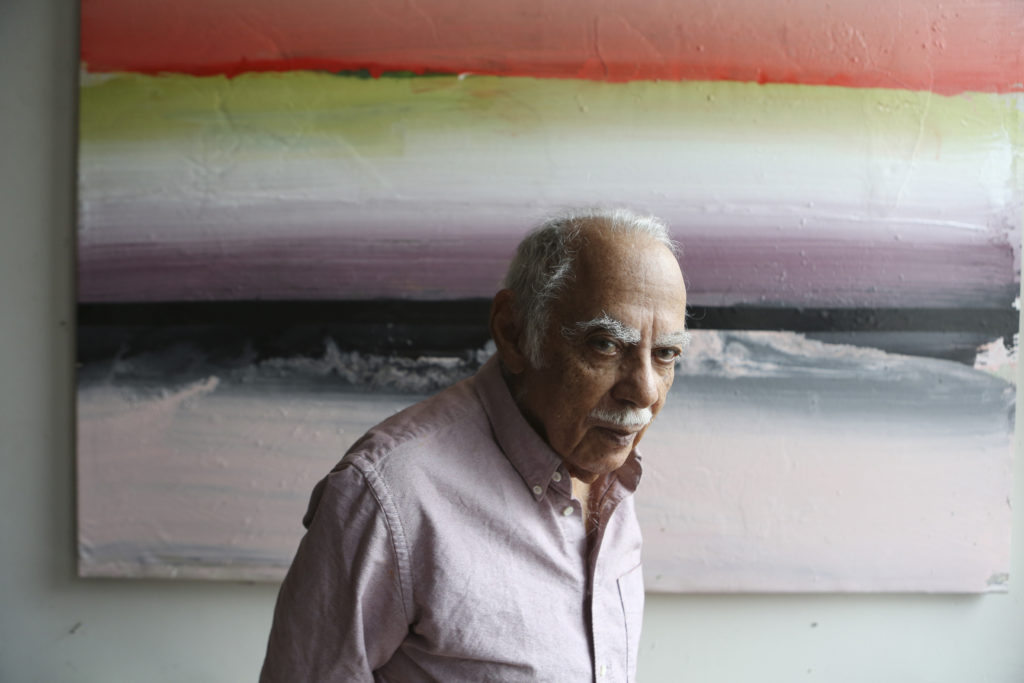

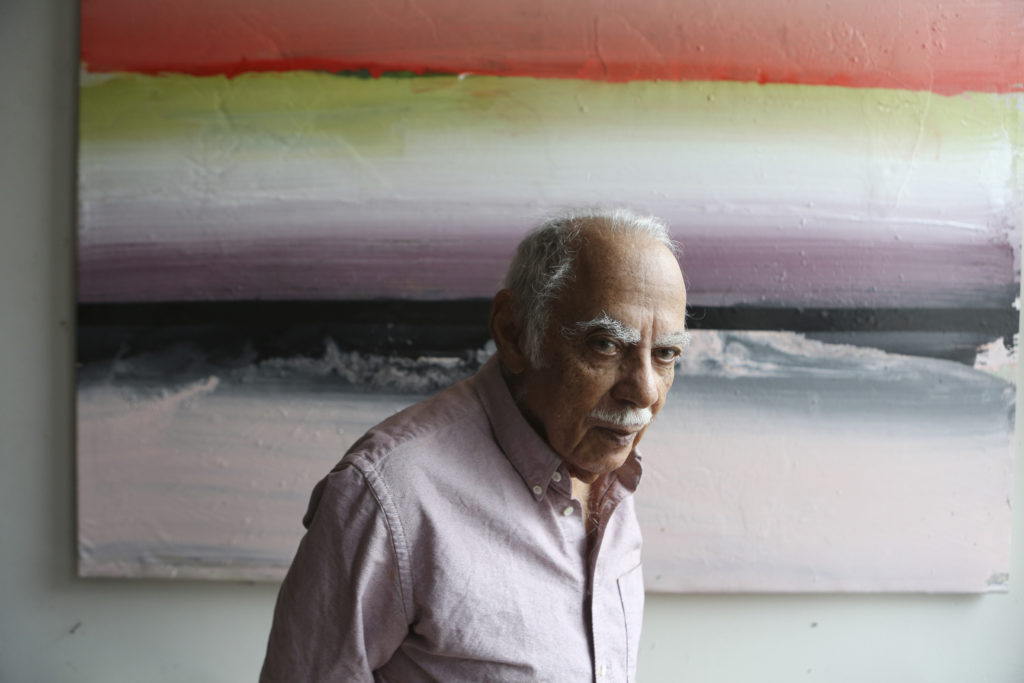

Ed Clark.

CHESTER HIGGINS JR./THE NEW YORK TIMES

The artist Ed Clark, whose radiantly colored abstractions charted exhilarating, inventive, and elegant new paths for painting, has died at the age of 93 in Detroit. The gallery Hauser & Wirth, which represented him, announced the news on Friday night.

Over the course of more than 60 years, Clark earned a reputation as a ceaseless innovator—one of the key abstract painters of the postwar period. In 1957, he showed one of the first shaped canvases. Just a year earlier, he had begun developing a method of producing luminous, action-packed paintings on his studio floor by pushing paint with a broom, a technique he honed thereafter.

Clark was, for a long stretch, known as something of an artist’s artist, a figure admired by friends and peers like Donald Judd, Joan Mitchell, Jack Whitten, and David Hammons even as many important museums and powerful dealers ignored his work. As an African-American man, certain possibilities in the mainline art world were closed off for him.

“I couldn’t get into a commercial gallery where a white person was running it,” Clark once told Whitten in a wide-ranging interview. But he found other ways to show—helping to found a co-op gallery and sometimes renting spaces on his own, and his work found supporters. “I was making money any fucking way,” Clark went on. Leading dealers and museums would eventually come knocking at his door, though only late in life.

Ed Clark, Untitled, 2005.

© ED CLARK/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND HAUSER & WIRTH/PHOTO: THOMAS BARRATT

At the heart of Clark’s practice was his love for travel. He reveled in seeing how his work shifted when he painted in different locations, under different light. He spent long stretches in Crete, Martinique, New Mexico, China, Brazil, and elsewhere. “I’ve traveled everywhere with my art,” he once said. “Places that people wouldn’t go, I went.”

Edward Clark was born in New Orleans in 1926 and moved to Chicago with his family in 1933 as part of the Great Migration. He recalled classmates and some teachers praising his drawing abilities at an early age, which pushed him to focus on art.

But as a young child, Clark also became aware of the adversity he would face. He recalled a nun in kindergarten telling his class to draw a tree, with a gold star going to the best artist. Clark was certain he won. “She came to mine—she didn’t like me for whatever reason—and rather than give me the gold star, she just dismissed the class,” he told Whitten. That made me realize [that] I could be the best all my life and not get recognized.”

Before finishing high school, at the age of 17, he joined the U.S. Army Air Force to participate in World War II, and served in Guam. At the war’s end, he enrolled at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago on the G.I. Bill, even though he did not have a high school degree, and then decamped in 1952 to further his studies in Paris.

Installation view of ‘Ed Clark Paintings, 2000–2013’ at Hauser & Wirth, New York, West 22nd Street, 2019.

© ED CLARK/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND HAUSER & WIRTH/PHOTO: DAN BRADICA

Living in the French capital, he became part of a circle of expatriate African-Americans who included the writer James Baldwin and the painter Beauford Delaney, and it was there that he would shift from making immaculately rendered representational art into abstraction, after becoming fascinated by the French painter Nicolas de Staël.

“When I first saw his work, I didn’t even know it was figurative,” Clark would recall later, as he described his encounter with de Staël’s work depicting football players via thick, flat slabs of color. Only later, reading about it in the newspaper, did he discover its actual subject, he said. “I didn’t even know that or care.”

Working in his studio in Montparnasse one day, he found himself wanting a wide brush, and discovered a janitor’s broom in his building. “I started using it right away,” he said in a 2015 interview with the Pérez Art Museum Miami. With that, he was on on his way to making some of the signal works of the era, which shimmer with disparate colors and an ineffable élan.

Clark termed his broom method “the big sweep,” and he told the writer Quincy Troupe in 1997 that what it provided was “speed. Maybe it’s something psychological. It’s like cutting through everything. It’s also anger or something like it, to go through in a big sweep.”

Ed Clark, Untitled,

1978–80.

BROOKLYN MUSEUM/COURTESY OF WEISS BERLIN/PHOTO: STUDIO LEPKOWSKI

After returning to New York in the mid-1950s, he fell in with the thriving Downtown art scene that centered on Abstract Expressionism, congregated on 10th Street, and drank at the Cedar Tavern. Along with other future giants, like Al Held and Nicholas Krushenick, he founded the co-op gallery Brata in 1957, where he would show that early shaped painting, a scintillating, untitled abstraction on a rectangular panel to which he affixed a slice of painted paper that spilled beyond the work’s edges. (It now resides at the Art Institute of Chicago.)

Clark’s paintings in the ensuing decades exude the rare and exquisite sense of having come instantly into being with just a few pushes of his broom. Their brash, joyous confidence comes from the tool’s movement, but also from his unique sense for color—where, say, mint green, lava red, and aquamarine can hover together gloriously.

He painted un-stretched tondos that can recall magnificent sunrises, splattered paint in quick attacks on canvas, and sometimes turned brooding, gliding dark, shadowy forms alongside one another. Clark’s most recent work, from the past few decades, can have a particularly explosive presence, a few vibrant glides made atop unprimed canvas. There is nothing else like them.

Like many Black artists of his generation, Clark was historically sidelined in many accounts and exhibitions of the period, though he showed continually, and he had retrospectives at the N’Namdi Center for Contemporary Art in Detroit (in 2011) and the Studio Museum in Harlem (1981).

Ed Clark, Untitled, 2006.

© ED CLARK/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND HAUSER & WIRTH/PHOTO: THOMAS BARRATT

Clark bristled at his work being categorized as “Black Art,” the critic Antwaun Sargent wrote in a 2018 essay on the artist, but he took inspiration from the Black Arts Movement, comparing its energy to what he had experienced on 10th Street earlier in his career. “So both times when I came back from Paris after a long stay, it was like a shot in the arm,” he said in an interview with art historian Judith Wilson, quoted by Sargent, in which the artist recalled his return in the city in the late 1960s. (At one point, he traveled to Cuba with the movement’s cornerstone figure, writer LeRoi Jones, later to be known as Amiri Baraka.)

In recent years, Clark’s star had risen, with his work appearing in the traveling exhibition “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power” and major one-person shows at Mnuchin gallery (a 2018 survey) and Hauser & Wirth (2019), both in New York. Those exhibitions had been preceded by two solos at Tilton Gallery in New York, in 2014 and 2017, the first of which was curated by Hammons, a longtime friend who collected his painting.

Improvisation was essential to his art, Clark said in the interview with the Pérez Art Museum. He would look around his studio, select a few colors, and start experimenting. “When I get into painting like that,” he said, “you don’t get into something that you understand, right? You just let it go.”

[ad_2]

Source link