[ad_1]

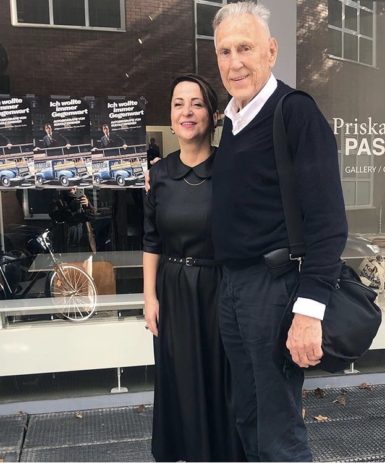

Rudolf Zwirner, right, with Priska Pasquer, whose gallery now occupies his former space in Cologne.

© PRISKA PASQUER

Non-German speakers, you’ll want to warm up your Google Translate for this one. Dealer Rudolf Zwirner—aka mega-gallerist David’s dad—recently gave an extensive interview to the Tagesspiegel on the occasion of the release of his autobiography from the publisher Wienand (that’s also German-language only—so far).

If the name Rudolf Zwirner doesn’t mean anything to you, it is time to change that. Zwirner had a gallery first in Essen, Germany, in the early 1960s, and then in Cologne, and, along with 16 other dealers, he started the world’s very first art fair, Art Cologne, in 1967 in the city’s Gürzenich festival hall. (The annual event is still going strong, these days in the city’s convention center, helmed by unflappable former art dealer Dan Hug, who happens to be László Moholy-Nagy’s grandson.)

Zwirner, who closed his business in 1992 (the year before David’s opened in New York), told his Tagesspiegel interviewer—Nicola Kuhn, who also ghostwrote his autobiography—why he started Art Cologne:

I already exhibited Pop art artists Jim Dine, Andy Warhol, and Roy Lichtenstein in the late 1960s, but no one was interested. There were hardly any visitors, the press ignored us. So I decided to go to London with my gallery, where there was a vibrant pop and fashion scene. At the last moment, I changed my mind because a good friend, who maintained a gallery there, advised me against it. Without a lord in the background, a financier, I would not stand a chance, she said. Then I returned to Cologne. I knew we had to change the structures if we wanted to sell young art.

Zwirner, 86, wanted to bring in a new audience for contemporary art, reaching not only connoisseurs but also people who might be intimidated by galleries’ reputation for snootiness. “The word fair alone brought art closer to the vegetable market than to the museum,” he told Kuhn.

Since then, of course, contemporary art has gone from a tough sell to in-hot-demand, with astronomical prices to match. I phoned Zwirner at his home in Berlin and found that, these days, the inventor of the modern art fair is not so sure that model is the best way for galleries to go.

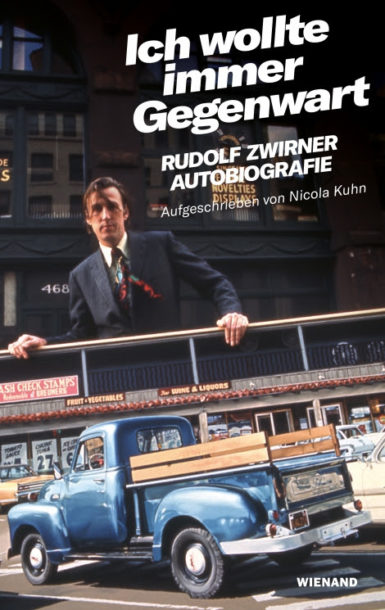

The cover for Rudolf Zwirner’s new autobiography, written with Nicola Kuhn.

WIENAND VERLAG & MEDIEN

I asked him, as the person who cofounded the first art fair, does he think we are coming to the end of the art fair age?

“There will always be fairs,” he said. “But the real collectors—the ones who are looking for the artists, with no money”—the ones he was going after with the first Art Cologne—“they don’t go to fairs anymore. [Something like] Basel—it doesn’t help the art. It’s money, another way of having an auction.”

“When we started Cologne,” he went on, “we wondered, would we be able to do it a second year? Would there be enough major works? Now artists are making work for the fairs. It’s totally crazy. We need paintings!”

He laments the pressure the fairs are putting on mid-tier galleries who have far fewer resources than the megas. “Art fairs are extremely dangerous and expensive for younger galleries,” he said. “I invented the art fair but now I have to tell galleries: Find another way. Find something to do in your gallery.”

During our conversation, he bemoaned the rampant monetization of art, and the fact that it is so hard for many of us these days to look at it without seeing dollar signs. “You go to someone’s apartment—especially in the U.S.—and you see on this wall, a million dollars, on this wall, two million.”

But Zwirner remains sanguine about the art business overall. “There will be a solution,” he said. “Maybe not fairs anymore—finished. But another way.” He firmly believes the art world needs to go “back to the analogue. Small events. Tell people why you are showing this art, why it’s so important.”

I asked Zwirner about an episode I’d read about, during the second edition of Art Cologne, when the artist Joseph Beuys protested the fair based on its exclusivity. “Beuys came to protest the commercial aspect and . . . to shut down the art fair,” Zwirner recalled. “He wanted to go in before the opening, for the press conference. I told him, this is the press conference. The opening is in the afternoon. You are not a member of the press. But it’s ironic: he was protesting the art fair with his huge crew of people. And a huge piece by him sold for 100,000 marks. So he was making money inside and protesting outside. Eventually his group came into the fair and a table was made available for them so they could write down their protests.”

[ad_2]

Source link