[ad_1]

In 1970, a group of art collectors gathered at a ritzy New York penthouse apartment on Fifth Avenue, a stone’s throw away from where the late Jackie Onassis once lived. The occasion was a pre-opening dinner party for the artist Georgia O’Keefe, whose retrospective was being put on by the Whitney Museum. The scholar, curator, and artist David C. Driskell was invited to the affair, having lent O’Keeffe’s Radiator Building (1927) on behalf of the Nashville’s Fisk University, where he chaired the art department at the time. Upon arriving at the building, Driskell was greeted by a doorman who asked if Driskell was there to “report to work.” In his 2009 Archives of American Art oral history, Driskell remarks that he benevolently told the doorman that he was there as a party guest.

As he was escorted into the party, an overzealous white man took it upon himself to “appease” Driskell, one of the few Black people at the party, by remarking about the slow progress of Civil Rights in the American South, to which Driskell eloquently responded, “You’re talking about an American problem; this is not just a Southern problem.” He continued, “I live in Nashville, Tennessee, I have lived there for the past two or three years. And this evening as I came into this building, the doorman stopped me and asked me if I was reporting to work. That hasn’t happened to me in Nashville, but this is the North.” There was silence, and then the partygoers went on with their celebration.

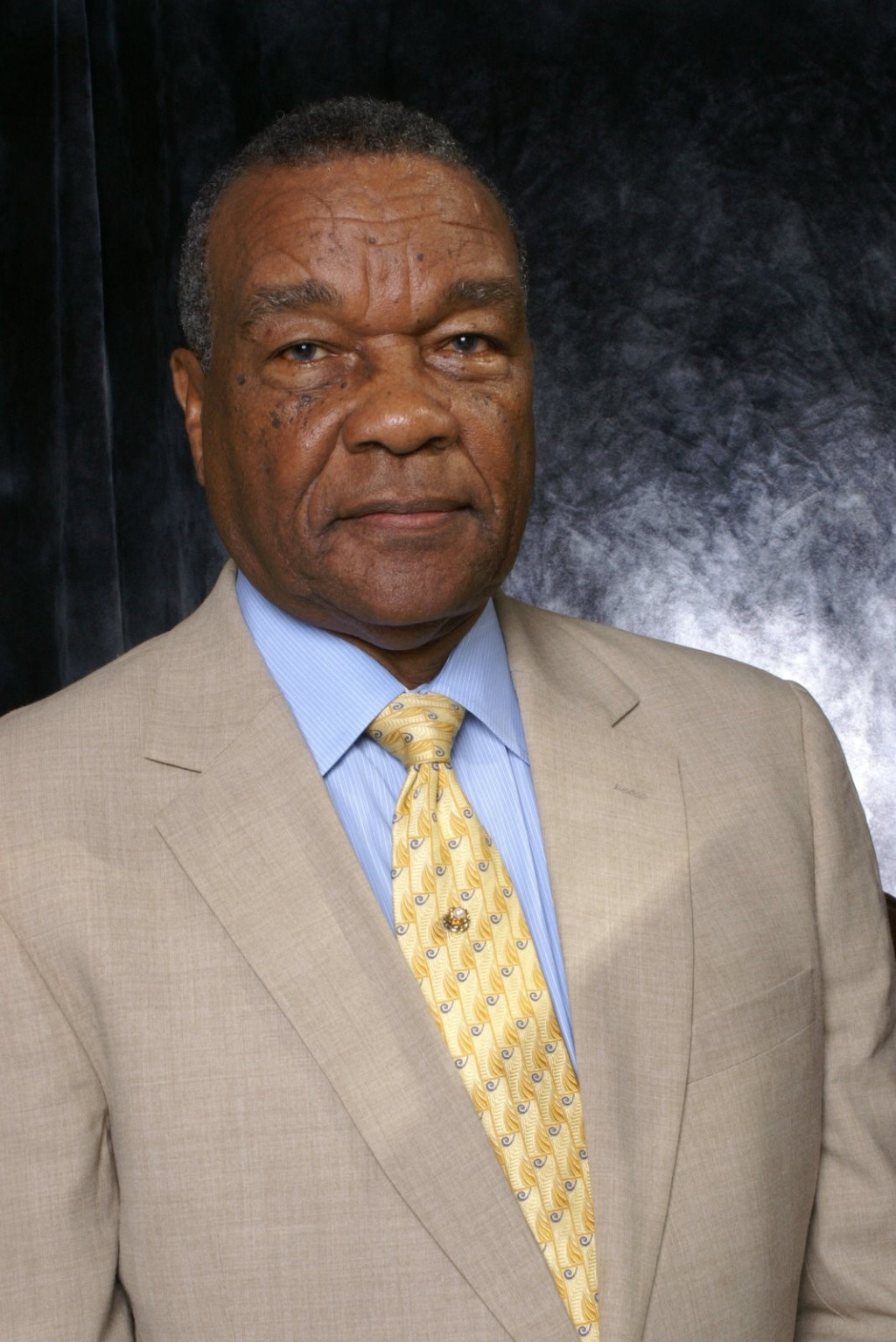

This brief anecdote is emblematic of the ways in which Driskell made himself known within predominately white institutional spaces devoted to American art—places that have been sustained by the erasure of Black creativity and labor. Driskell, who died last week at 88 years old, was in some ways, an outlier in those spaces, as a sustainer of African American art. He not only contributed to the development and expansion of Black art and culture within the American art canon, but also insisted on the importance of conveying the truths of Blackness and its complicated discontents.

[Read the ARTnews obituary for Driskell.]

I came to know Driskell’s work while studying as an art history student at his alma mater, Howard University. Driskell’s work—along with that of historians Samella Lewis, Sharon F. Patton, James A. Porter, and Floyd Coleman—was my introduction to the field of (African) American art history. His word ushered me in, instilling in me a desire to always consider how life functions inside and alongside the artmaking. His approach was holistic in how he tended to the artistic lineage of Black folks, and why we attend to a method of beauty. A sense of generosity ran through everything he did. I only met him once, briefly, but I came away reminded of what a tangible resource he was—a phenomenon who always seemed willing and ever-giving to the generations of us who were fortunate enough to follow in his footsteps.

As we celebrate and give thanks for the many gifts he has given personally, collectively, and professionally to those of us who work in this field, we should consider what it means to work against the grain of continued erasure when there have been little to no examples of how to go about such an ambitious task. What is required of a person to insist that they belong in “mainstream” spaces guided by ignorance? How does one develop the courage to hoist and insert the authenticity of a culture that has been continuously misunderstood, misrepresented, or made invisible?

Courtesy Los Angeles Museum of Art

Six years after that encounter at the Fifth Avenue penthouse, Driskell organized a seminal exhibition of African American art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, “Two Centuries of Black African American Art.” The curatorial impulse driving the show—and its subsequent iterations at the High Museum in Atlanta, Georgia and the Brooklyn Museum in New York—was to de-isolate and de-marginalize Black artists in the canon of American art. Furthermore, it insisted that these creators—artists like Dave the Potter, Thomas Day, Joshua Johnson, Edmonia Lewis, Robert S. Duncanson, Henry O. Tanner, Palmer Hayden and contemporaries Jacob Lawrence and Romare Bearden—were indeed humans who are “no different from any other in [their] struggle to express [their] own individual sensitivity to order and form, and at the same time relate to the cultural patterns of the time in place in which he lives,” as Driskell put it in the show’s catalogue.

Many white critics failed to understand what a watershed moment the exhibition was. New York Times critic Hilton Kramer wrote in his review that “we ought to just be talking about quality art and not trying to get everybody in.” When Driskell was brought on as a guest to The Today Show, he was asked by Tom Brokaw about Kramer’s comments. Driskell responded, “Hilton Kramer? What does he know about black art?” Driskell simply could not—would not—endure myopic takes from people he construed as nonblack gatekeepers within the art world.

Emerging within a world mired in white supremacy and white creative production and elitism, Driskell was never less than hopeful about pushing Black American creativity forward. Driskell was born in Eatonton, Georgia, and when he was five, he moved with his family to the Blue Ridge Mountains in North Carolina. Amid the segregationist American South, Driskell traveled over 30 miles a day to attend school, where he was educated by teachers who echoed the sentiments of his parents, a Methodist-turned-Baptist minister and a housewife. If you desire a world beyond what you know, you must get an education. And so, he did, enrolling in 1949 at one of the most prominent historically Black colleges, Howard University (colloquially dubbed “the Mecca” by its students), where he began as a history student. That is, until he became enamored of the work of James A. Porter, one of the first scholars to establish the field of African American art, and switched his major to art and art history.

In addition to Porter’s guidance, Driskell learned studio art and art history from professors Louis Mailou Jones, Morris Louis, James Wells, and James V. Herring. Washington D.C., and more specifically, Howard University became an incubation site, that later influenced Driskell’s scholarship, and extended on Porter’s foundation of African American Art history. Driskell ended up returning to Howard to teach years later, after having established the art department at Talladega College in 1955. His return as an educator took place during the height of the Black Power movement. Howard University, he said in his 2009 oral history, “was a very exciting place to be at that time. It was the center, the hub for activity relating not only to civil rights situations but to the political scene, and the antiwar effort.” The scholar taught painting and a modern art history course to enthusiastic students like Kwame Ture (then Stokley Carmichael) and Mary Lovelace O’Neal.

It seems that his work as an artist also imbued a certain sensibility within him that was prescient and dynamic. Early in his painting career, he spent a summer at the Skowhegan School of Painting & Sculpture in Maine, where he studied painting with artists Jack Levine and Varnum Poor. Both impressed upon him a desire to paint social realist themes. Soon after his time at Skowhegan, Driskell made the 1956 painting Behold Thy Son, in which he immortalized Emmett Till, a Black boy who had been killed the year before by a mob of white men in the Jim Crow South for allegedly whistling at a white woman. (The allegations were later proven false.) Cast in muted brown, gray, and off-white hues, Driskell offered an image of a Black Christ with abstracted yet youthful features. A maternal female character, cast in shadows, presides over this premature crucifixion.

Courtesy the artist and DC Moore

While Driskell did not entirely abandon social realism and representational work throughout his artistic career, he leaned more into abstraction and sometimes deferred to nature and other spiritual elements for inspiration later in his life. Works like Shango (1972) and Current Forms: Yoruba Circle (1969) elicit vigorous movement from shape, color, composition, and abstracted mask forms. The works also serve as symbolic markers for his first visits to the African continent, and his continued study in making visible the allegorical umbilical cord that connects diasporas between Africans and Black Americans.

[See a slideshow of Driskell’s art.]

Such a deep understanding of history guided his curatorial endeavors, principal among them “Two Centuries of African American Art.” In her book South of Pico: African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s, scholar Kellie Jones wrote that the show that “reminded the public that people of African descent in the United States had been around and creative for hundreds of years and that amazingly, given their circumstances for much of that time, they had made some beautiful things.” The exhibition was an art-historical feat, if not a humanitarian one. It ushered in a new history of art that widened not just many people’s ideas of beauty, but also of what it means to be human and American. In an era, where the market insists that Black artists are impermanent darlings, Driskell’s assertion was that Black artists had been integral to the project of (white) modernism altogether.

In the later stages of his career, Driskell’s work grew introspective. In 1996, after an already long career in academia and artmaking, Driskell created the work Echoes: Let the Church Roll On (1996), an homage to his father and his childhood memories in his father’s churches. In it, the artist offers a vibrant scene of a soft red church house with loose strokes of thick and colorful spiraling lines that surround it. The lines gesture into subtle tree, plant, and flower formations. Rendered with encaustic, gouache and crayon on paper, the compressed, yet fluid landscape contains a Black angel figure positioned vertically above the church. The figure, clasps a book of scripture in one hand, while the other rests on the steeple of the church. The sight recalls Driskell’s childhood, growing up in church houses, entranced by the ministry of his father.

Of that period, he remarked, “what [my father] taught me was that there is something beautiful in everything.” Driskell then carried this inclusive reading of aesthetics to the art canon writ large, teaching us all how to see beauty in places that were intentionally overlooked. In doing so, he created multiple cartographies for the beneficiaries of his lineage, that continue to be illuminated by his grace, courage, and generosity.

[ad_2]

Source link