[ad_1]

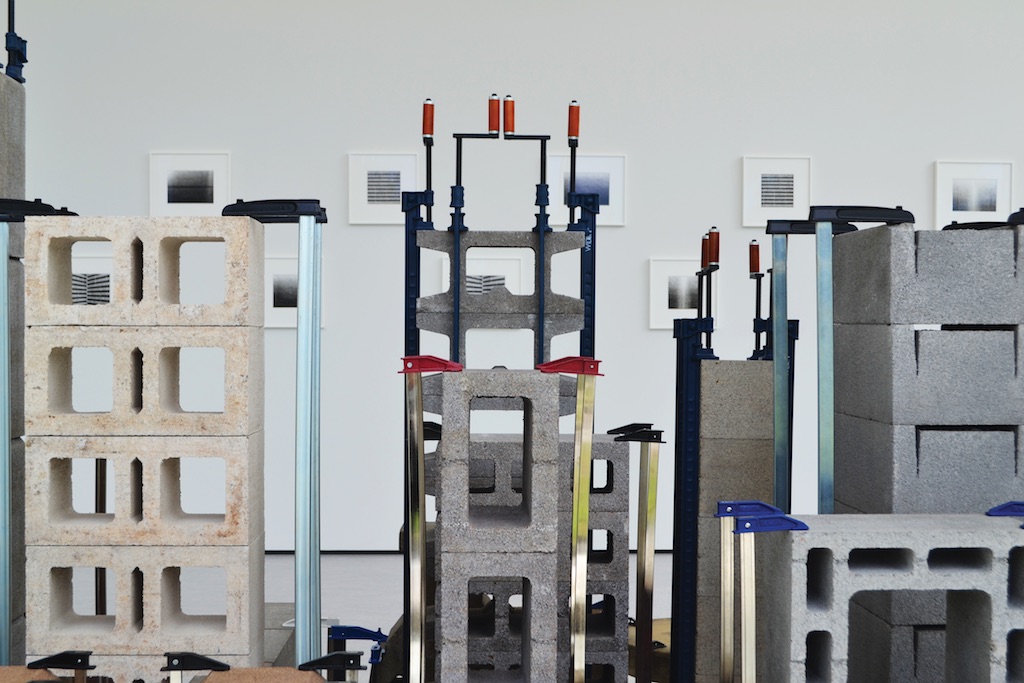

Marlon de Azambuja, Brutalismo-Cleveland, 2018, foreground; Luisa Lambri, Untitled, 2017, background, installation view.

ALEX GREENBERGER/ARTNEWS

An international art triennial in Cleveland: how about that for an oxymoron? It’s an understatement to say that Cleveland lacks the glamour of other festival-hosting cities: Venice’s sun-dappled canals, Berlin’s world-class gallery scene, the all-around intrigue of São Paulo, Sharjah, Shanghai, Sydney, Dakar, Istanbul. Part of the thrill of those events for international visitors is getting immersed in the city and contemplating how the exhibition rubs against it, revealing certain aspects of the locale.

But recent political events have made Cleveland—and other American cities that are not New York, L.A., Chicago, or Miami—an illuminating place to study, and the inaugural edition of Front International had much to tell about its host metropolis. Under artistic director Michelle Grabner, “An American City: Eleven Cultural Exercises” had as its remit finding new ways to explore metropolitan areas and communities; it put the spotlight on sites that are off the beaten path, evoking the curatorial style of the Prospect New Orleans triennial. Its venues include three museums, a steamship, a market, a hospital, a theater, a mall, a warehouse, the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, two churches, and various local institutions, as well as offshoots in the nearby cities of Akron and Oberlin.

The architecture and landscape of the Rust Belt are reference points for many of the triennial’s artists. Several of them used the show as an occasion to address the continued relevance of modernism in Ohio. At the Cleveland Museum of Art, Marlon de Azambuja is showing what appears to be a small-scale city constructed from cement blocks and clamps. Alongside this work is a series of Luisa Lambri photographs featuring zigzagging black-and-white forms; careful observation reveals that they’re close-up shots of the CMA’s Marcel Breuer–designed building. Both works offer new views of Breuer’s heavy, industrial materials, in ways that seem to be personal for both artists. They find their equivalent in Cui Jie’s paintings and 3D-printed structures, which recycle Constructivist and Bauhaus techniques to imagine futuristic-looking skyscrapers, and Ad Minoliti’s beguiling photocollages, which feature digitally rearranged images of modern interiors.

Katrín Sigurdardóttir, Namesake, 2018, installation view.

FIELD STUDIO

Throughout the triennial, artists transpose aspects of their own lives to Ohio’s public spaces. In a plaza outside the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland, Tony Tasset debuted the newly commissioned Judy’s Hand Pavilion, a 20-foot-tall, silver-toned sculpture of his wife’s hand. Its surface is disconcertingly realistic, mottled with veins and wrinkles. In a pathway near Cleveland’s Detroit Superior Bridge, Katrín Sigurdardóttir had installed a patch of clay bricks made from materials brought over from her native Iceland. The bricks had already begun breaking apart during the triennial’s opening weekend, and greenery was sprouting through, as though to suggest that Sigurdardóttir’s heritage and Cleveland’s landscape were merging.

Other artworks reflect a research-intensive approach, braiding together dissimilar histories in an attempt to reveal common threads. Allan Sekula’s remarkable, nearly three-hour film, The Lottery of the Sea (2006), a long-form essay on bodies of water, intertwined urban planning in Barcelona, the shipping industry in Panama, classic movies starring Humphrey Bogart, and World War II–era submarine warfare in Japan. Grabner gives it local context by exhibiting it in a retired 20th-century steamship docked in Lake Erie, near Cleveland’s Great Lakes Science Center. At MOCA, Cyprien Gaillard’s 3D video Nightlife (2015) links a Rodin sculpture outside the CMA to a nearby high school, trees blowing in the wind in Los Angeles, and a fireworks show over a stadium in Berlin, which Gaillard shot via a soaring drone. There are complex historical connections between all these locations, but Gaillard hasn’t made them obvious; he seems content to revel in the poetry of it all.

This sense of interconnectedness extends to the triennial’s nod to urban sprawl—a fitting topic for a city whose borders continue to expand. Grabner’s curatorial sprawl includes an online portion of the triennial, “Digital Infinities,” where most of the artists, among them Chris Dorland, Jonathan Horowitz, and Alix Pearlstein, focus on the proliferation of images on the internet. The most striking work is Siebren Versteeg’s Thoughts Without a Thinker (FRONT: Woodstock), 2018, a grainy 24/7 webcam feed of the artist’s studio in Woodstock, New York, that’s occasionally interrupted by spliced-in images lifted from Google by AI. Cities, the piece suggests, are no longer just physical space—they include cyberspace, too.

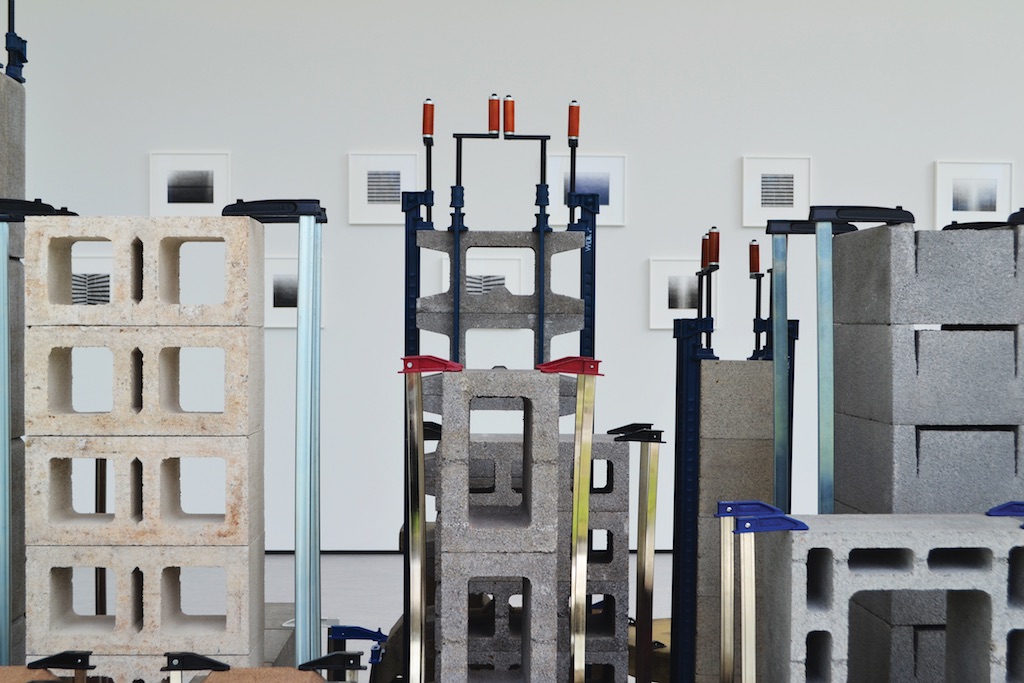

Yinka Shonibare MBE, The American Library, 2018, installation view.

ALEX GREENBERGER/ARTNEWS

Like other American cities, Cleveland has absorbed victims of the world’s current refugee crisis. Cleveland.com reported last year that the local refugee population jumped 69 percent between 2012 and 2016. Accordingly, a number of artworks in Front, many of them sensitive and urgent, reference migrations and voyages. Those travels, some works suggest, can be seemingly banal—a Jessica Vaughn sculpture included 33 seats removed from Chicago buses, all worn down by years of commuters sitting on them, in reference to the distances black and immigrant residents must travel to get to the city’s more affluent neighborhoods. But most works go for grander statements about how our world is shaped by constant exodus, spurred by both personal choice and force.

Nowhere was this more apparent than in Yinka Shonibare MBE’s The American Library (2018), a bookcase lined with more than 6,000 tomes housed in the Cleveland Public Library. Each book was inscribed with the name of an immigrant or a person who’d decried immigration—Huey P. Newton, Alex Katz, Julian Stanczak (whose work was included in the triennial), and Julia Alvarez were among the names I glimpsed. (I was told that Stephen Miller, a senior adviser to Donald Trump, was included.) This bombastic celebration of immigration was countered by John Riepenhoff’s far more modest Cleveland Curry Kojiwurst, a sausage made in collaboration with local butchers and farmers that is being sold at Cleveland’s West Side Market throughout the triennial’s run. What better metaphor for Cleveland, which once had a large population of Central and Eastern European immigrants, many of them Jews, than sausage, a food that crosses cultures through its mélange of meats and spices?

Dawoud Bey, Night Coming Tenderly, Black, 2017, installation view.

FIELD STUDIO/COURTESY THE ARTIST, RENA BRANSTEN GALLERY, AND STEPHEN DAITER GALLERY

A few other pieces in Front overtly referenced Cleveland’s history with migrants, but none of them haunted me in the same way as Dawoud Bey’s photo installation Night Coming Tenderly, Black (2017). It was displayed in St. John’s Episcopal Church, once the final stop on the Underground Railroad before fugitive slaves crossed Lake Erie into Canada, and Bey drew on that history, offering a series of images tracing the 460-mile distance from Hudson, Ohio, to Cleveland as those slaves would have traveled it mostly by foot. Bey’s photographs depict branches, lakes, and fences that he edited to make just barely visible amid the night-dark landscape. Mounted atop the church’s pews, as though meant to be worshipped, they invite viewers into an empathic connection with people on a treacherous journey.

Some artists took a more aggressive tack. In a series of videos from 2004–05 by the now defunct Visible Collective, the viewer is told that he’s “gotta understand” that being black and Muslim is “a concern in this country.” The videos were shown near Nasser Al-Salem’s Arabic calligraph in neon, Arabi/Gharbi, meaning “Arabic/Westerner.” Pondering the role that privilege plays in who gets to represent whom, Candice Breitz’s Love Story (2016) was a video installation that featured actors Alec Baldwin and Julianne Moore reenacting stories that the artist collected in a series of interviews with real-life refugees. “I didn’t do bad things,” Baldwin, who plays a Venezuelan refugee, says to Breitz. “I was made to do bad things.” His performance is concerning because it’s so convincing.

Pao Houa Her, My grandmother’s favorite grandchild, Duachi, Goncoley, Lilian and Mai Youa (detail), 2017.

COURTESY CLEVELAND INSTITUTE OF ART

The first Front International is just as fascinating for what it doesn’t represent as for what it does. Few Latin American and indigenous artists are included, and the focus is largely on work by those based in major urban centers. (And despite the catalogue’s claim to provide a feminist perspective on cities, just 35 percent of the artists identify as women.) Much of what’s on view is excellent, but where are the local artists? Out of the more than 110 artists included, just 12 are based in Ohio.

To be fair, Grabner, who is based in Milwaukee, includes a section that advocates for artists from the region, and it’s one of the triennial’s finest offerings. “The Great Lakes Research,” a group show at the Cleveland Institute of Art, features 21 artists based in Chicago, Detroit, Toronto, Cleveland, and other Great Lakes cities. That was where I made a few discoveries: Pao Houa Her, whose terrific photographs depict Hmong people adjusting to Western settings; Joe Smith, who offers an air freshener as a pesky readymade; and Alan Belcher, whose wall-mounted sculptures are based on icons that appear on iMac computers. That exhibition said more about art in the Great Lakes region today than anything else on view.

A few of the Ohio artists Grabner included are terrific: the Oberlin-based Johnny Coleman has an excellent sound installation about local history at an old church, and Julie Ezelle Patton is offering tours of her Let It Bee Ark Hive, for which the artist brought her works together with those by her deceased mother (who was also a Cleveland-based artist), and combined them to create the ersatz collages she scattered throughout her apartment-size installation. But these works are few and far between, and the Coleman and Ezelle Patton pieces are a mile’s walk from the CMA, MOCA, and the CIA, on the fringes of the Glenville neighborhood. Many of my colleagues visiting from out of town weren’t even aware that they existed.

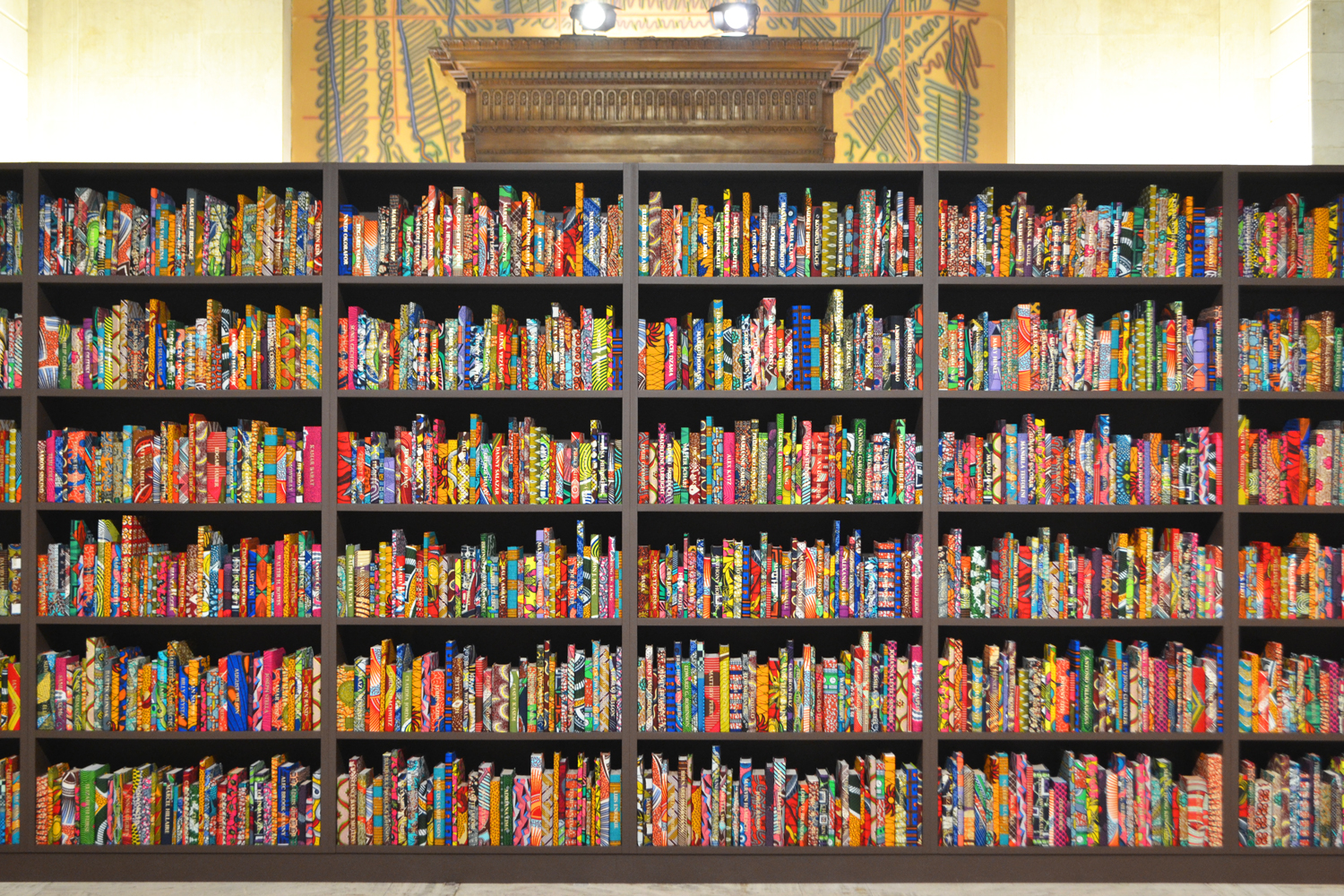

Lin Ke, Here and Now (screenshot), 2018, augmented reality video.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

Becoming more local is, oddly enough, the theme of an engaging work by an out-of-towner: the Chinese artist Lin Ke, who has crafted an augmented reality piece called Here and Now (2018) at MOCA. When one’s phone is held up to wall prints that depict low-resolution images of museum spaces, a series of videos becomes visible. One video begins with a folder called “linke-for-Front” being clicked on an Apple desktop. What follows is a succession of folders being opened, from a big one called “Universe-folder” to a tiny one called “in mind.” Lin, who did a residency in Cleveland as part of the triennial, has gone from the general to the specific by sorting through various data, and in the process, he’s understood his place within the world. As it prepares for its second edition, set to open in 2021, the Front International would be wise to do the same.

[ad_2]

Source link