[ad_1]

Christo, who died on Sunday at the age of 84, will always be remembered for the intense visual spectacle of his wrappings, many of them produced with his wife Jeanne-Claude. Yet those fond memories of flowing fabric and dramatic alterations to sites and structures often obscure matters of controversy surrounding Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s art. Below, a survey of the scandals that figured in five of Christo’s most iconic works.

Jan Bauer/AP/Shutterstock

Wrapped Reichstag (1971–95)

The meaning of many of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s wrappings could be elusive, and when the couple pursued a wrapping of the Reichstag, a Berlin building with a complex political history, many officials raised their brows while wondering whether the artists were accidentally—or even purposefully—promoting German nationalism. First erected in 1894, the Reichstag was home to assemblies until 1933, when a fire that severely damaged the building became a catalytic event for the Nazis, who claimed the blaze was proof that Communists were trying to destroy Germany.

What did it mean for the artists to want to wrap a structure with such a fraught history, especially in the years of Germany’s reunification and following the fall of the Berlin Wall? German politicians were split on the project’s significance. “We need not avoid all experimentation, but because of what the Reichstag represents, it should not be the subject of experimentation,” one member of German Parliament said. Another claimed the opposite, calling the wrapping “a wonderful cultural symbol of our new beginning in Berlin.” In the end, despite fierce debate, the wrapping was approved and later lauded by critics—even the ones who pointed out that its symbolism was ambiguous.

Shutterstock

The Gates (1979–2005)

The first time Christo and Jeanne-Claude tried to execute The Gates in New York’s Central Park was in 1980. It didn’t go so well. Each time the artists presented plans for The Gates, which called for the creation of arch-like structures with large pieces of fabric hung from them, they were met with adversity for its $5 million price tag and for the way it would so dramatically alter one of Manhattan’s most instantly recognizable sites. “Here’s an event of 27 miles of shower curtains around the park,” one attendee at a press conference told Christo. “Is that necessary, Mr. Christo, to promote yourself?” City officials didn’t think it was, and subsequently canned the project.

Signs that the long-gestating project might come to fruition could be seen in 2001, when, a year before he became New York City’s mayor, Michael Bloomberg urged his fellow trustees at the Central Park Conservancy to consider allowing the artists to realize The Gates. After Christo and Jeanne-Claude revised their original proposal, city officials granted consent. When the work was realized in 2005, tourists flocked to see it. Critics were polarized, however. In Artforum, Jeffrey Kastner wrote, “Like all their work, The Gates represented a wager (their biggest yet) that the most popular public art will necessarily be the product of private enterprise. In this pay-to-play time, it was a sucker’s bet, and one they won convincingly.”

Pete Wright/AP/Shutterstock

Surrounded Islands (1980–82)

Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s biggest wrapping to date remains Surrounded Islands, which saw land masses in Miami’s Biscayne Bay ringed in 6.5 million square feet of flowy pink fabric. The epic project was met with a fittingly epic outcry from locals. Perceiving an ecological threat to ospreys and eagles because of the propylene used by the artists, environmentalists protested the work, with some even tying pink garbage bags in the form of a bow around a Miami courthouse. And then there was the astronomical cost of the project—$3 million (around $8 million now, when adjusted for inflation)—and the most common insult lobbed at Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s work: that it was an eyesore.

Christo, the more public-facing figure of the two artists, frequently heard out these complaints and found ways of methodically responding to each of them. As with most works by the couple, extensive reports about worker payments and environmental impacts were issued, and city officials were offered pages and pages of data about how the work would be executed in advance.

Nick Ut/AP/Shutterstock

The Umbrellas (1984–91)

At first glance, plans for The Umbrellas did not seem ripe for misfortune. The work involved the placement of oversized umbrellas in two very distant valleys—one in Japan, the other in California. The arrangement of the umbrellas was intended to spotlight the agricultural differences of their locations, and as usual for Christo and Jeanne-Claude, it proved to be quite an attraction, with an estimated 3 million people having made the journey to spend time under the umbrellas, each of which weighed 485 pounds.

But The Umbrellas proved tragic, sadly, when on a windy day in California, a woman was crushed by a sculpture that fell. Christo instantly demanded that the work be deinstalled early and expressed sorrow, telling the Associated Press, “I will live with that tragedy to the end of my life.” The controversy did not end there: a worker in Japan died while removing the piece, leading critics to allege that Christo’s egocentrism had blinded him and kept him from completely thinking through safety concerns.

Elio Villa/Agf/Shutterstock

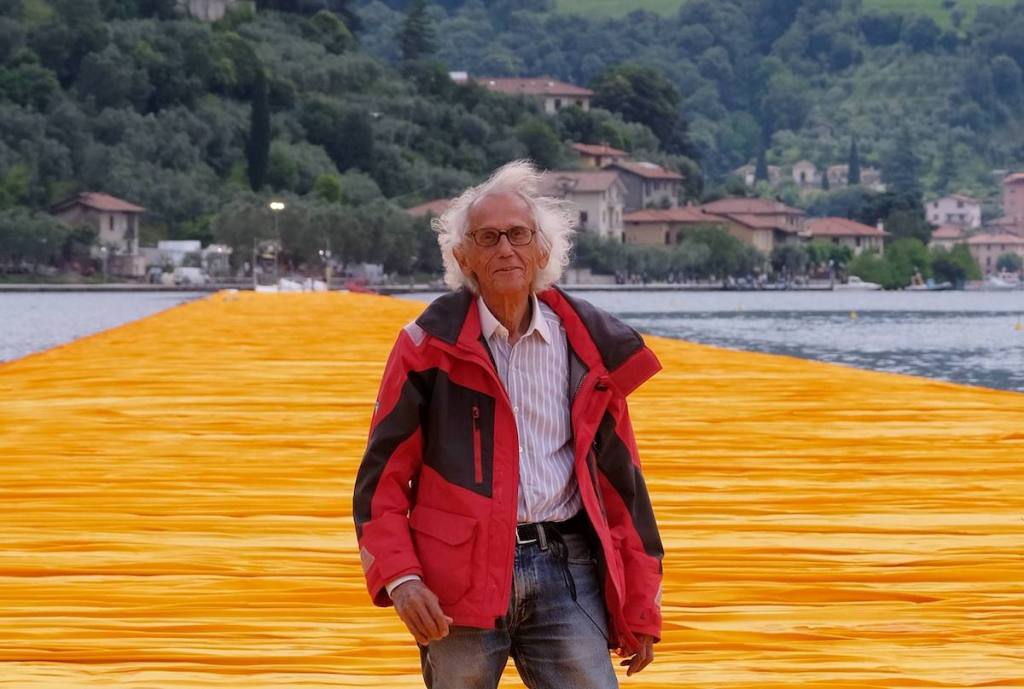

The Floating Piers (2014–16)

One of the few monumental wrappings that Christo produced solo, The Floating Piers was staged in Italy’s Lake Iseo in 2016. Over the course of two weeks, an estimated 1.5 million people flocked to walk across the work, which resembled a dock-like structure covered in richly hued fabric. But, in spite of the joy many felt while trekking across it, the piece was fraught with controversy during its making. Various reports suggested that Christo funded the project’s whopping €15 million budget himself. Yet some Italians were suspicious, and a consumer rights group filed a complaint with a court in the Lombardy region that demanded that citizens be provided with information about whether tax money had gone toward the work.

Even after The Floating Piers was removed, the work continued to provoke. In 2018, Artnet News ran a report on the art-world financial endeavors of the Beretta family, which owns a gun manufacturing business. The report did not conclusively state whether the Berettas had funded The Floating Piers, though it did note that a private island owned by the family was lent to Christo for the work. Christo declined to comment.

[ad_2]

Source link