[ad_1]

By David Crary and Regina Garcia Cano, The Associated Press

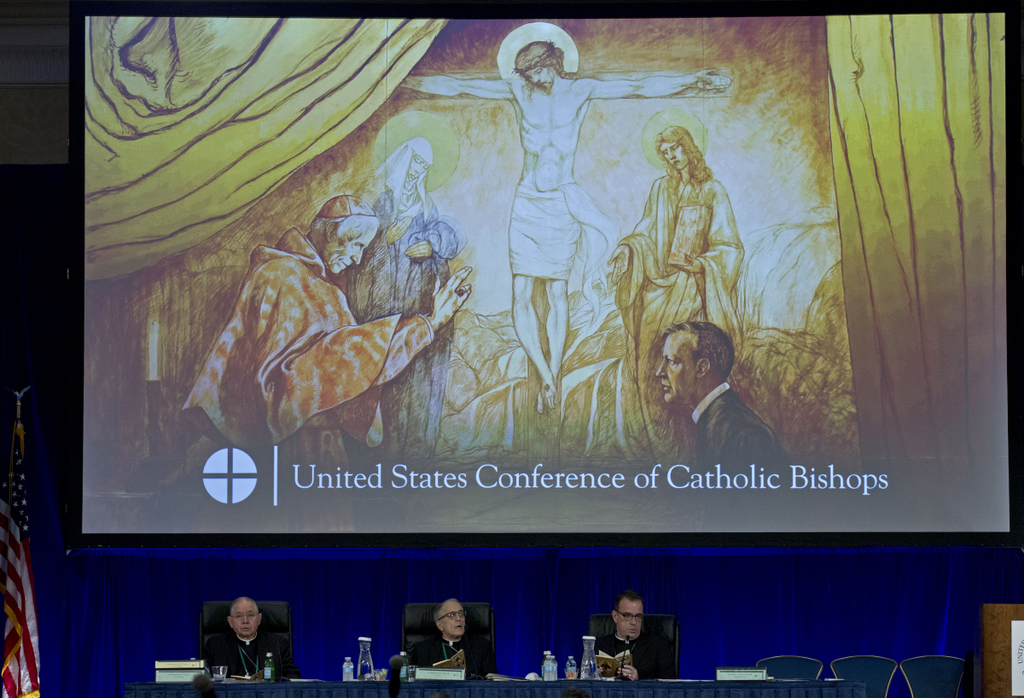

Under intense public pressure, the nation’s Roman Catholic bishops approved new steps this week to deal more strongly with the clergy sex-abuse crisis. But activists and others say the moves leave the bishops in charge of policing themselves and potentially keep law enforcement at arm’s length.

As their national meeting in Baltimore concluded June 13, leaders of the U.S. bishops conference stopped short of mandating that lay experts such as lawyers and criminal justice professionals take part in investigating clergy accused of child molestation or other misconduct. They also did not specify a procedure for informing police of abuse allegations that come in over a newly proposed hotline.

“Even the bishops themselves recognize they have lost their credibility in monitoring this dreadful crisis,” said Thomas Groome, a professor at Boston College’s School of Theology. “Without strong oversight by competent lay people, it won’t be seen as credible.”

Groome said the bishops should have no hesitation in declaring that credible allegations should be reported to police.

“They’re not dealing simply with a sin, they’re dealing with a crime,” he said. “They do not have the power to forgive crimes.”

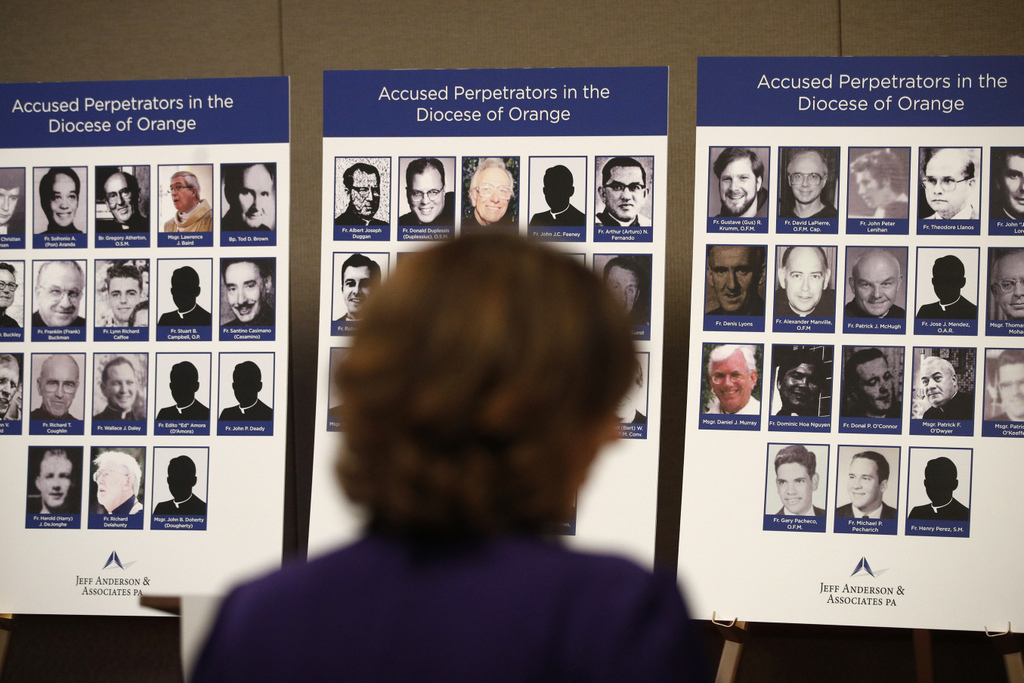

The Baltimore meeting followed a string of abuse-related developments that have presented the bishops and the 76-million-member U.S. church with unprecedented challenges. Many dioceses around the country have been targeted by prosecutors demanding secret files, and a number of high-ranking church officials have become entangled in cases of alleged abuse or cover-ups.

According to a recent Pew Research Center survey, the crisis has led about one-quarter of U.S. Catholics to reduce their attendance at Mass and their donations to the church. Even some bishops sense that many Catholics are distancing themselves from the church because of the furor.

“One of the terrible costs of the scandal is costing people their faith,” said Cardinal Joseph Tobin of Newark, New Jersey. “So I think it’s entirely right that we give priority to this.”

Of the anti-abuse measures approved by the bishops during three days of deliberations, the most tangible was the planned creation of a national hotline — to be operated by a yet-to-be-chosen independent entity — to field allegations of abuse and cover-ups by bishops.

The allegations would be forwarded to a regional supervisory bishop, who would have the task of reporting to law enforcement and the Vatican and deciding if lay experts should investigate the complaint.

Another measure specifies that the bishops will now be governed by the same code of conduct that has applied to priests since 2002. It outlines a variety of procedures for combating child sexual abuse and says even a single act of abuse should lead to a priest’s permanent removal from the ministry. Catholic leaders say the charter has helped greatly to reduce clergy sex abuse.

During Thursday’s debate, Bishop Shawn McKnight of Jefferson City, M0., urged that lay involvement in investigations be made mandatory, “to make darn sure we bishops do not harm the church.”

The bishops did not go quite that far, instead stipulating that archbishops “should identify a qualified lay person to receive reports.”

The auxiliary bishop of Detroit, Donald Hanchon, said the new measures are a step in the right direction.

“I feel like we accomplished something instead of just saying, ‘We are sorry these things happened,’” he said. “People need more than that.”

However, SNAP, a national advocacy group for victims of clergy abuse, expressed dismay that the bishops did not mandate lay involvement or spell out a policy for notifying law enforcement.

“Without these mandates, there is no guarantee that reports will be routed to police and investigations will be transparent and public,” SNAP said. “Instead, all reports can remain secret and insulated within the church’s internal systems.”

SNAP also called on Catholic leaders to strengthen the network of lay review boards that help Catholic dioceses across the country investigate abuse cases. SNAP said these boards should be fully independent of diocesan control and include at least one abuse victim, as well as experts recommended by the attorney general’s office in the diocese’s state.

Tobin said some dioceses and archdioceses, including Newark, already have arrangements with local prosecutors that entail the reporting of any criminal activity.

“I’m confident that the idea of doing this in house is long gone,” he said.

One of the highest-profile scandals of the past year involved former Cardinal Theodore McCarrick of Washington, who was expelled from the priesthood for sexually abusing minors and seminarians. Last week The Associated Press reported that Cardinal Daniel DiNardo, who heads the bishops’ conference and the Galveston-Houston Archdiocese, was accused by a Houston woman of mishandling her allegations of sexual and financial misconduct against his deputy.

___

Crary reported from New York. Associated Press reporter Nicole Winfield in Rome contributed to his report.

[ad_2]

Source link