[ad_1]

Klaus Biesenbach in front of the Barbara Kruger installation at MOCA Los Angeles.

MYLES PETTENGILL/COURTESY THE MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART, LOS ANGELES

Visible to thousands of commuters, business people, area residents, and tourists slogging through civic center traffic less than a month before the 2018 U.S. midterm elections was this message, spelled out in block letters each some five feet high: “WHO IS BEYOND THE LAW? WHO IS BOUGHT AND SOLD? WHO IS FREE TO CHOOSE? WHO DOES TIME? WHO FOLLOWS ORDERS? WHO SALUTES THE LONGEST? WHO PRAYS LOUDEST? WHO DIES FIRST? WHO LAUGHS LAST?” The work of artist Barbara Kruger, it reprised her famous mural originally displayed on the facade of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles’s Geffen Contemporary building during a turbulent time in L.A. history, from 1990 through the L.A. riots in 1992. Reinstalling the mural was the first thing Klaus Biesenbach did in his new job as MOCA L.A.’s director. He told the Los Angeles Times it “comes to mind as one piece that, in a way, stands for MOCA, its history and role in the city. It encourages us to engage and mobilize to participate. It shows us how an artist can create a timeless, unafraid truth, and beauty that does not age.”

MOCA is at it again, trying to re-create itself with new leadership. This time—the third such upset in 10 years—Biesenbach is in the hot seat. An up-to-the-minute curator with a passion for community outreach and social justice, the 52-year-old German native made his name in Berlin as the founder of Kunst-Werke Institute for Contemporary Art and the Berlin Biennale. He has spent most of the last two decades in New York, chalking up curatorial and administrative experience at the Museum of Modern Art and MoMA PS1.

“I thought I was in an ideal world,” Biesenbach said of his dual position as chief curator-at-large of MoMA and director of the independent art center in Queens that became an affiliate of the Manhattan museum in 2000. “But this is an incredible opportunity,” he continued, taking a deep breath at the end of his first week on duty in Los Angeles. “It feels like a moment when you can really make a difference here.”

Few would argue with that. But the position comes with a lot of baggage. With a stellar postwar collection, an extraordinary exhibition record, two commodious showcases downtown and an outpost in West Hollywood, MOCA established itself 39 years ago as the anchor of L.A.’s contemporary art scene, and quickly evolved into one of the world’s best museums of its kind. But then came a devastating financial crisis and a problematic recovery.

Despite a $30 million bailout by philanthropist and collector Eli Broad and a subsequent fund-raising campaign that catapulted the endowment to about $135 million—more than triple its historic high—the museum has yet to restore confidence in its stability and regain its former stature. While other venues for contemporary art have proliferated in Los Angeles, MOCA seems to have lost ground, and the last three directors have left under duress. Jeremy Strick resigned in 2008 as part of Broad’s bailout agreement. Jeffrey Deitch bowed out in 2013 amid a storm of criticism about his flashy program and the forced departure of longtime chief curator Paul Schimmel. Philippe Vergne decided to step down this past May when he learned that his contract would not be renewed, apparently because of a dispute that led him to fire chief curator Helen Molesworth, but he agreed to stay during the search for his successor.

It remains to be seen if Biesenbach will break that pattern and guide MOCA into a brighter future. Early skeptics have lamented that the museum missed an opportunity to hire someone other than a white man. They have also criticized his affinity for celebrity culture and questioned his administrative credentials. But the museum’s trustees are squarely behind him.

“The most qualified candidate has joined us,” said Maria Seferian, an attorney and MOCA veteran who was elevated to the position of board chair in a recent reorganization. “With his guidance, we will implement his vision. I’m excited to see his program.”

She and the rest of us will have to wait for that. Biesenbach’s reinstallation of Kruger’s 1990 mural Untitled (Questions), made a big splash in mid-October, just before his official arrival. Painted on a highly visible outdoor wall of MOCA’s Geffen Contemporary facility in Little Tokyo, the 30-by-191-foot artwork asks pointed questions about money, politics, and power. The preelection timing was no accident, even as the mural seemed to set the stage for a new regime. But in sharp contrast to that headline-grabbing event, most of Biesenbach’s work is going on behind the scenes.

“Aggie Gund advised me to grow slowly and listen to everybody first,” Biesenbach said, quoting his favorite mentor, a New York arts patron who chairs the board of MoMA PS1. “That’s what I’m doing right now. I want to spend the first half-year just learning and listening. That prevents you from doing things too fast or coming to conclusions that are not fully informed.”

Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Obodo (Country/City/Town/Ancestral Village), 2018, an adhesive vinyl installed on the museum’s exterior.

ELON SCHOENHOLZ/COURTESY THE ARTIST, THE MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART, LOS ANGELES, AND VICTORIA MIRO, LONDON/VENICE

His listening started last summer, when he talked to 37 trustees individually before agreeing to take the job. Since then, he has consulted with Richard Koshalek, who directed MOCA in its glory days; Joel Wachs, a former Los Angeles city councilman and MOCA trustee who is now president of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts in New York; leaders of arts institutions in Los Angeles; and various artists. To his delight, some of his outreach took the recipients by surprise.

Wachs was not well acquainted with Biesenbach and hadn’t heard about his MOCA appointment when his call came, but he emerged from their meeting with cautious optimism. “Klaus Biesenbach values MOCA’s history. He’s also of the moment, attuned to cultural changes,” Wachs said. “He enjoys raising money and does it well. He brings celebrities—but in a good way—to support the museum. He is capable of doing what he wants to do. The question is: What is he going to do?”

Biesenbach, who maintains a notably quiet but intensely engaged demeanor, offered a broad answer in the form of a mission statement: “A museum is not a reflection of the art market. A museum is not an ornament. A museum is a civic offer of generosity, a place where art can be seen and experienced, where we can talk about art, people can express their opinions, and young people can learn about art. It’s a really important civic institution that delivers generously and allows access. It is very educational and it’s very much one of the areas in society where we can talk freely about the human condition and how artists see it, and reveal truth and beauty in what they see. If you try to be of service, it’s not about blockbusters, but providing access to a place where artists like to present their work and it is presented in the right way.”

More specific indicators of Biesenbach’s plans lie in the groundwork that began a couple of months before he moved to Los Angeles and settled into his downtown living quarters, where he can walk up to the museum’s Grand Avenue headquarters in seven minutes and down to the Geffen Contemporary in ten. While getting acquainted with the elegant Grand Avenue building, which has 24,000 square feet of exhibition space, he talked to early MOCA supporters about how the Arata Isozaki–designed structure was intended to work and expand, and thought about ways to celebrate the permanent collection there.

At the Geffen, a former police car garage owned by the city and renovated by Frank O. Gehry, Biesenbach envisions a town square. With about 40,000 square feet of indoor space and an additional 11,500 square feet outdoors, the site might be set off from an ugly parking lot by greenery and sculpture, he said. The building should remain open, not closed for long periods as in the past. Exhibitions can be programmed so that something is always on view. Storage areas can be cleaned out and used as part of a free public space amenable to time-based art, performance, and a wide variety of activities.

Daunting as that might sound, Jimmy Van Bramer, a New York City councilman whose district includes MoMA PS1, pointed out that Biesenbach has a record of making the museum a much more welcoming place to its neighbors, with community nights and special events as well as a summer “Warm Up” series of music and dance programs. He also noted that Biesenbach turned the Rockaway Artists Alliance into a destination by staging installations in an abandoned building nearby by such superstars as Patti Smith and Yayoi Kusama, and that he spearheaded relief projects for victims of Hurricanes Sandy and Maria.

“Klaus is a very talented organizer who juggles hundreds of things at a time,” Van Bramer said. “He is incredibly detail-oriented and does not miss a thing. He will give a lot of thought to the administrative piece of the job of directing a world-class cultural institution. He brings to Los Angeles unparalleled connections, not only to New York but also all over the world, and that can only be good for MOCA.”

Eschewing “any big announcements,” Biesenbach said that he and the board will be engaged in “a process of stabilizing, consolidating, and improving,” not inventing a new museum. As part of that process, they will work on diversifying the museum’s staff, audience, and program. Praising MOCA’s five curators—Bryan Barcena, Anna Katz, Rebecca Matalon, Bennett Simpson, and Lanka Tattersall—and its director of education and programs, Amanda Hunt, as “excellent,” he said that others would be added with a goal of assembling a “diversity of voices” and expertise.

He also discussed the hot topic of free admission, which is fundamental to broadening the museum’s audience. “With the lost revenue and increased security, it would cost around $2 million a year to have free admission,” he said. “With a $20 million budget, that’s not nothing. Together with the board and staff, I have to find how to get there and how long it would take. It’s definitely a declared priority and has been since the get-go. To serve as a public museum, you should be free. But I don’t want to promise. It’s always better to under-promise and over-deliver.”

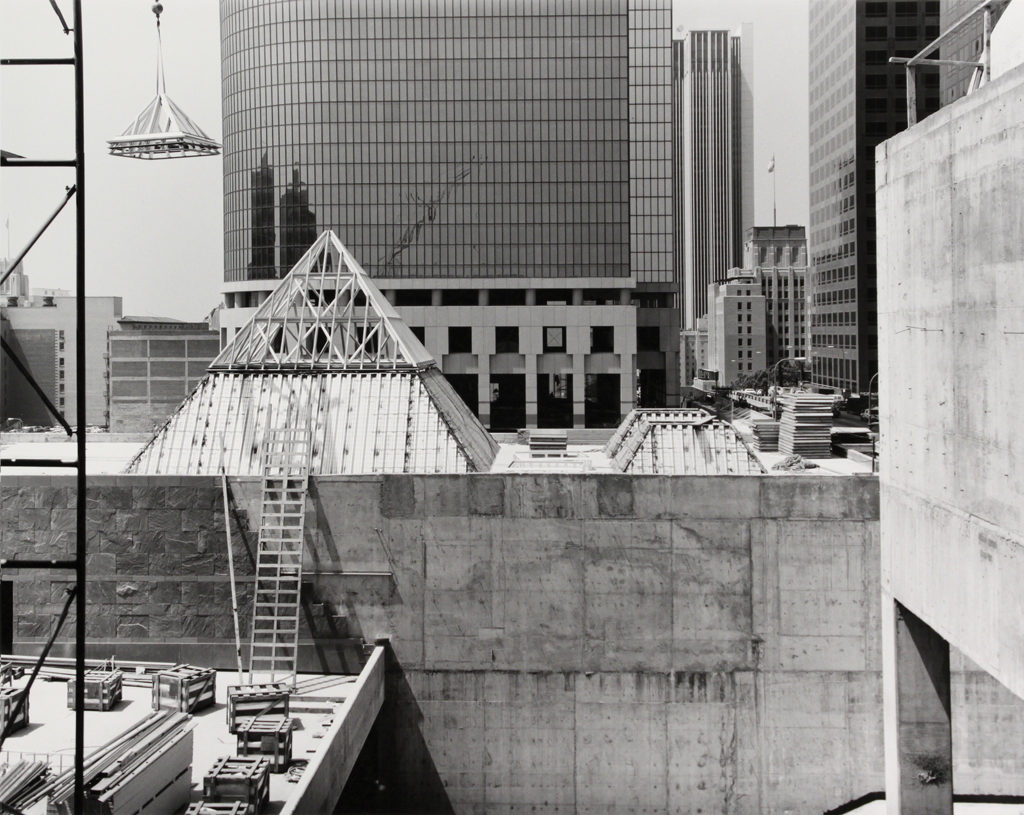

Joe Deal’s Lowering Gallery B Pyramids shows MOCA while its Grand Avenue building was under construction.

COURTESY THE MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART, LOS ANGELES

MOCA rose from the ashes of the Pasadena Art Museum, a prominent showcase for contemporary art that fell into debt and evolved into the Norton Simon Museum in the mid-1970s. At the time, it was a devastating defeat for the contemporary art crowd. But Pasadena gained a cultural jewel devoted primarily to Simon’s collection of historical art from Europe, India, and Southeast Asia, while supporters of the original museum, including Simon’s sister, Marcia Simon Weisman, channeled their anger into action.

Wachs introduced Weisman to L.A. Mayor Tom Bradley, who listened carefully as she made a case for creating a new contemporary art museum. A core group of private citizens, including Broad, raised the initial endowment. The city, in turn, provided the proposed museum with the Little Tokyo building for $1 a year, and a free new building that fulfilled a “percent for art” requirement at the California Plaza redevelopment project on Bunker Hill. Founded in 1979, the fledgling museum opened the Geffen, then called the Temporary Contemporary, in 1983. The Grand Avenue new building was completed in 1986.

MOCA won international credibility in 1980 by giving its top job to Pontus Hultén, founding director of the Centre Pompidou in Paris. The L.A. museum pulled off another coup in 1984 with the purchase of 80 Abstract Expressionist and Pop works from the collection of Giuseppe Panza for the bargain price of $11 million. Although Hultén returned to Paris in 1983, Koshalek, his deputy director, stepped up and presided over MOCA until 1999. What followed was a remarkable period of collection building and landmark exhibitions organized by Julia Brown, Ann Goldstein, Paul Schimmel, Elizabeth A.T. Smith, Kerry Brougher, and other curators. Koshalek’s successor, Jeremy Strick, maintained a high-level exhibition program with Schimmel as chief curator, but it became unsustainable in 2008, when a recession hit and the endowment plunged from around $40 million to $6 million, partly because it had been drained to pay operating expenses.

That’s when Seferian appeared. With a background in business law, she landed at a museum with a $19 million operating budget and no income. “The revenues came entirely from the trustees on a current basis year after year after year, so we had to figure out what to do,” she said. After much discussion, the best two options were a merger with the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and a gift agreement with Broad. “We went with Eli to preserve the independence of the museum,” she added.

Broad’s $30 million package extended over five years. Half the money was designated for exhibitions, with $3 million given each year. The remaining $15 million had to be matched. Deitch, an enterprising contemporary art dealer from New York, became MOCA’s fourth director in 2010, while money was flowing in. But the bailout ended and the financial outlook became grim. “There we were again in 2012, and this generous gift hadn’t sustained our independence,” Seferian said. “It’s really important to remember that we don’t have a large benefactor like the Getty. We don’t have the county or the city. We don’t have an educational institution to backstop us. We just have ourselves.”

“So again we were talking with LACMA and other institutions,” she continued. “The easiest thing in 2012 would have been to hand over the keys. But preserving MOCA is really important, so we decided that if another organization can fund-raise on us, why can’t we do it ourselves?” The result was a campaign that exceeded its $100 million goal with trustee gifts, topped off by a $22.5 million auction of artworks donated by artists, at Sotheby’s New York in 2015.

“When I look back on that, there has been a lot of criticism about the board, and I get it,” said Seferian, who was MOCA’s interim director between the regimes of Deitch and Vergne. “But it’s important to understand the dedication that the board has had in the last 40 years. They care.”

David G. Johnson, an entertainment attorney who co-chaired the board from 2008 to 2013, heartily agreed. Differences of opinion among trustees are normal, he said, adding that it’s the publicity about MOCA’s past problems that has been unusual. “The board throughout its history has been the primary financial support, by far, for the museum and [for] building the collections,” he continued. “The problem for so long was . . . financial weakness, but with the endowment campaign I think we fixed that. The board is committed not only to MOCA’s independence but to its thriving independence.”

The buzzword these days is “alignment.” Over the years, artist trustees have been some of MOCA’s most public critics, sometimes resigning from the board in protest over staff firings or a perceived lack of unity and transparency. But Catherine Opie is back. She returned to serve on the search committee that selected Vergne, stayed on and did it again this year, along with fellow artist Mark Bradford. “We need to see what Klaus envisions, get aligned, and work together,” she said. “We need to build a future out of MOCA’s history. It’s important to consider what it means to be contemporary.”

Looking back on the interview process, Biesenbach recalled a moment in late June when he met with a large group of trustees, listened, and gave honest feedback. He doubted that they would talk to him again, but decided “if all these people can align,” he would take the job. “I think MOCA is ready to slowly grow again,” he concluded.

A version of this story originally appeared in the Winter 2019 issue of ARTnews on page 68 under the title “Just Like Starting Over.”

[ad_2]

Source link