[ad_1]

This summer, as Black Lives Matter protesters dodged rubber bullets fired by police and Black and brown communities were hit hard by COVID-19, book clubs sprang into being, and into action.

Shoshanna Hecht, an executive and personal coach from New York City, had just joined a book club themed around racial justice in March; she also signed up for a Zoom study group that would complete Layla F. Saad’s “Me and White Supremacy” workbook together. Joanna Mang, an adjunct English instructor in North County San Diego, was invited to join a new book club, called the Equity Re-Education Discussion Group, by a friend from her Stroller Strides group.

Ja’Rod Morris, founder of the Atlanta-based book club Black Men Read, didn’t have to form a new group. “The truth is, we have been having these conversations about police brutality,” he told HuffPost. Though the club was designed for literary discussion rather than activism, any space where Black people gather, he said, is a good space for political mobilization. “We’re on the front lines. We are the subject of this.” As the protests broke out, he called a “state of emergency” meeting to discuss how members could get involved.

Many white Americans, however, have not been having these conversations. The protests following the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis seem to have changed that.

“I have been very, very surprised by the apparently sudden outpouring on the parts of what appears to be millions of people, many of them white, who realize, wow, we have a lot of work to do, we have a lot we need to learn in order to do that work,” said Dr. Crystal Marie Fleming, author of “How to Be Less Stupid About Race: On Racism, White Supremacy, and the Racial Divide.”

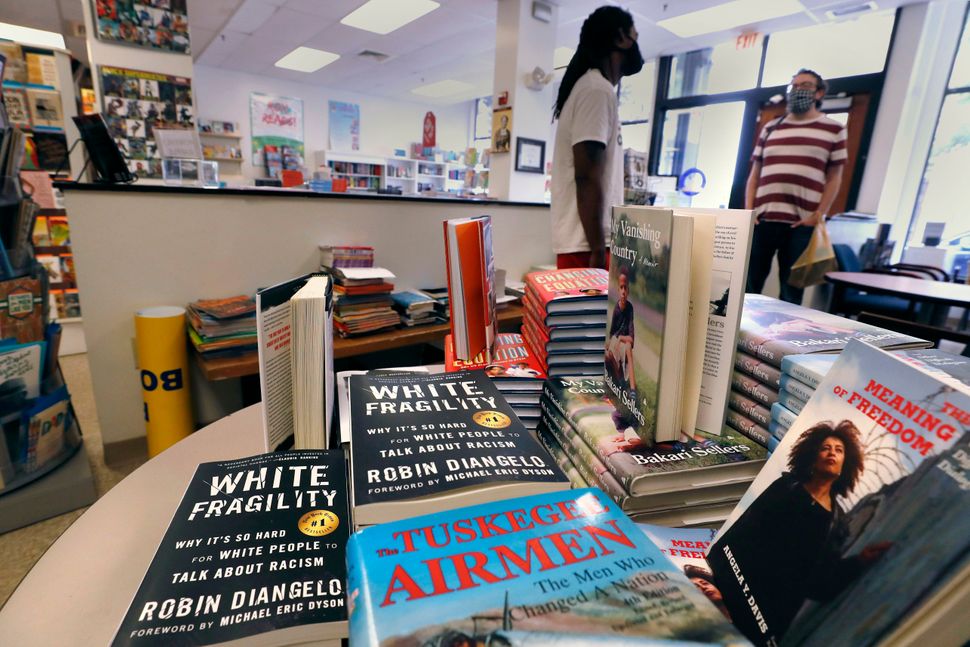

Since late May, it seems like every well-meaning, left-leaning white person in America has been trying to get their hands on a copy of “White Fragility” by Robin DiAngelo. Or “How to Be an Antiracist” by Ibram X. Kendi. Or “So You Want to Talk About Race” by Ijeoma Oluo. Or, hey, maybe all of them. Anti-racist manuals have been cleaned out from virtual bookstore shelves and pushed to the top of bestseller lists.

And often, these buyers don’t want to read alone. Enter the anti-racist book club.

Anti-racist book clubs hold great allure, and potentially great power, at a moment when many, particularly white people, are becoming conscious of their own educational blind spots around Black history and racial justice. Book clubs sit at a slippery nexus between education and relaxation, radicalization and affirmation; there’s a vibrant history of reading groups expanding people’s political consciousness and moving them to action, but also a deeply entrenched tradition of book clubs for white women as social spaces. This tension likely makes them an appealing starting point for people who want to dip their toes into the struggle for perhaps the first time, in a setting that they’re familiar with. The real test, of course, will be what comes next, once the book club attendees have gotten their feet wet with some radical reading.

The problem of white supremacy, said Dr. Fleming, a professor of sociology at Stonybrook University, “is not something that an anti-racist reading group will fix. It’s something an anti-racist reading group can help facilitate.” To make change, people will need to leave the warm uteri of their reading circles and put their knowledge into bold, concrete action.

“We have definitely seen a surge of interest in group reading for our anti-racist titles,” Sanj Kharbanda, sales and marketing director at Beacon Press, told HuffPost. Beacon publishes numerous anti-racism books, including “White Fragility” and Fleming’s “How to Be Less Stupid About Race.” He noted that this interest came from “traditional book groups” as well as clubs newly formed to discuss race. Churches, universities and bookstores have launched anti-racist book clubs (often virtual, in deference to social distancing measures); friends are organizing reading groups among their social circles.

Though it’s impossible to know exactly who is joining these groups, or even how widespread they are, it seems likely that those turning to literary discussion are disproportionately people who already participate in book clubs: mostly women, mostly well-educated, and mostly in their 30s or older. What could be more natural for a white woman who already belongs to a book club with her friends to ask that “How to Be an Antiracist” be the focus of next month’s meeting, or to start a spinoff group?

“A lot of people, a lot of college-educated women, seem to be attacking this problem from the books angle. What if I amass a lot of books — this has to be a way in,” Mang said. “They’re realizing that, now is a time that I need to be reading.”

But reading what? Despite the proliferation of reading lists, even picking the right book to read leaves some feeling paralyzed. More than one person HuffPost spoke to mentioned “White Fragility,” and the competing recommendations to read it (because it introduces white people to methods for decentering themselves during conversations about racism) and to not read it (because, among other concerns, it perpetuates the centering of whiteness and white feelings itself).

Mang, who has taught racial justice texts as a college instructor, had some pedagogical quibbles with “White Fragility”; she considers it dry, corporate jargon that does little to convey the urgent moral clarity of the issues to readers. Nevertheless, her club ended up reading it for their first meeting, and she was struck by the resulting discussion. “While I think ‘White Fragility’ is a silly book,” Mang said, “I think it could be a gateway.” Her group, populated with affluent, mostly white women, felt ready to get more radical in their reading afterward.

Kate Dearing, a TV writer based in Los Angeles, said that her club eased into things as well, reading “Stamped,” the young readers adaptation of Ibram X. Kendi’s “Stamped From the Beginning” by Kendi and Jason Reynolds. Her clubmate, Sami Kriegstein Jacobson, a creative consultant in New York, said there was an unexpected upside to the choice.

“After reading this book, I felt so frustrated at my own middle school and high school education,” said Kriegstein Jacobson, who attended a prestigious East Coast boarding school. “There was so much that was new to me in what was this actually very simple book that was meant for kids that age.”

She was so frustrated that she responded to the school’s latest donation solicitation by writing back to ask them what they were doing to decolonize the curriculum and to hire and retain teachers of color. “It made me glad that my eyes are open and that I could do something about it. I don’t know if we had started with a more rigorous book if I would have made the connection of, we should have been taught this so much earlier in life.”

For several years, the Bay Area chapter of Showing Up for Racial Justice (SURJ), a national organization which focuses on bringing white people into the struggle against white supremacy, has hosted study and action groups for allies looking to learn and get involved. Their ever-evolving, carefully designed curriculum goes a bit deeper than the most frequently recommended texts for beginners.

“We lean more towards articles, videos, speeches, relatively short pieces that we can group together,” Lizzie Humphries, one of the organizers behind the study and action reading group program, told HuffPost.

In shaping the curriculum, she and her fellow organizers were inspired by Black Panther study and struggle groups: spaces for learning and developing a shared political language that were inextricably connected to the on-the-ground work. Though the SURJ Bay Area groups do use “White Fragility” and other texts about how white people experience white supremacy, she said, “we really focus on pieces by authors of color.” Authors like James Baldwin and texts like the policy platform for the Movement for Black Lives, she said, “are really the central texts of the reading group.”

This focus, Fleming said, is key. Though “white anti-racists have a very important role to play in promoting anti-racist change,” she told HuffPost, “If your antiracist reading group or your antiracist initiative is not centering the work of Black people, indigenous people, and people of color, then they’re not antiracist.”

In choosing books to study, Carla Bruce-Eddings, a writer and senior publicist at Catapult/Counterpoint/Soft Skull Press, urged readers to “look to the work of queer Black women; they have been paving the way for radical thinking for generations.”

While curating the right curriculum is valuable, it’s not a panacea. “There’s no anti-racism checklist. It’s not something that can be mastered by reading a couple of books and it’s not something that can be bought,” anti-racist author and educator Tiffany Jewell said. Though sometimes, unsettlingly, it seems as though many white people believe otherwise. In a rich landscape of social justice literature, the skyrocketing sales of certain titles suggest not merely an eagerness to learn, but perhaps an almost talismanic attitude toward the most-recommended hits.

To see such a flurry of interest in anti-racist learning has been heartening for some. But for others, the timing and the type of action looks suspicious. As critic and academic Lauren Michele Jackson argued in a skeptical piece on the anti-racist reading list phenomenon in Vulture, the very word “anti-racist” “suggests something of a vanity project, where the goal is no longer to learn more about race, power, and capital, but to spring closer to the enlightened order of the anti-racist.”

This impression has only grown as Black booksellers have reported that customers have been quick to berate them for not shipping backordered titles popularized by these reading lists quickly enough. When I reached out to one Black-owned bookstore for this piece, an autoreply email responded that there would be a “SIGNIFICANT DELAY” in response time and asked for patience, as they were overwhelmed filling orders for in-demand anti-racist titles.

In July, Sruti Islam, events coordinator at Librairie Saint-Henri Books in Montreal, tweeted that after people had flooded the store with orders for anti-racist literature, they were failing to pick up their reserves; the tweet went viral. (After her tweet, she told HuffPost in an email, the store’s regulars “swiftly sent folks to pick up the remaining stock,” and the problem has not persisted.)

Besides, amid historic nationwide uprisings demanding an end to police brutality against Black people, surely buying a book or two is a tepid reaction to the state-sanctioned violence on display. Buying a book isn’t revolutionary; it’s easy, even a bit indulgent. In one sense, it’s a consumerist response to a crisis that calls for something deeper: putting bodies on the line. As writer Kelsey McKinney argued in June, turning to book purchases and book clubs can be a way of staying self-centered, of channeling newly aroused anxiety about racism back into spending money on yourself, spending time thinking and talking about yourself, and adding a new social activity to the calendar.

But there are practical reasons for many people to join a reading group as a way into, or a supplement to, anti-racist work. A deeper understanding of white supremacy and Black struggle can make newbies more adept at the nitty-gritty work, and forming bonds with like-minded people is a great basis for organizing. “I’m glad that white people are doing the work,” Bruce-Eddings told HuffPost. “They’re late, but I hope they’re reckoning with that too.”

Islam told HuffPost that Librairie Saint-Henri Books held outdoor, socially distanced book club meetings specifically in response to the demand for anti-racist literature. “We were concerned that people would be buying the books, Instagramming the books, and never actually engaging with the books,” she explained. “We wanted to bring back the book club in order to hold ourselves and these readers accountable.”

As white people grapple with the inadequacy of their good intentions and look into doing anti-racist work, many come to realize that one crucial form of it is countering racism within their own friend groups and families, as well as their own hearts and minds.

“We need to take initiative within our circles,” Kriegstein Jacobson said. “It’s our job to make sure to not only hold ourselves accountable but our friends, our families, our schools, our places of work.”

Being an effective advocate, however, requires a depth of knowledge that many are lacking. “A lot of people have more conservative family members and friends and they want to be able to talk to them,” said Mang of her book club. “Someone will say something, or write something on Facebook, and they’ll think, this feels wrong, but I don’t know what to say.”

Dearing said that in the past she found herself often staying silent instead of speaking up about racism she encountered because “I felt I didn’t know enough, that I didn’t know where I fit or how this would be useful or enough context, so I got scared that I would be called out.” Forming the book club was a way of building her resolve and her arsenal so that she would be prepared to, as she quoted late Rep. John Lewis, “make good trouble.”

“If your anti-racist reading group or your anti-racist initiative is not centering the work of Black people, people of color, then they’re not anti-racist.

Dr. Crystal Marie Fleming

A book club can provide a richer experience than just reading a book — a setting in which to practice having those tough conversations, other people to call you on your errors, and solidarity to strengthen your dedication. And, temptingly, it can mingle the tough intellectual work with social connection. This balance of joyful togetherness and political engagement can be valuable, said Bruce-Eddings, who has worked as books editor and helped plan festivals for the popular club Well-Read Black Girl.

“I think both things can happen simultaneously, and in fact, I think it’s more impactful when they do,” she said. She recalled her first Well-Read Black Girl meeting, where serious conversation about how the women could take action to change their lives was intermingled with lighthearted gossip and laughter. “As a Black woman, I’ve grown up very accustomed to witnessing and partaking in moments like this: the joy is inextricable from the pain, but that makes it all the sweeter. Political work has to be grounded in our humanity, otherwise it’s simply hypothetical; meaningless.”

As white people join anti-racist book clubs, the ideal approach may look a bit different. “A book club that is for Black women is going to have a completely different purpose than a book club for white people focused on their own [and small-group] learning/unlearning,” Jewell pointed out.

And the cozy kaffeeklatsch vibe may be too cozy to keep a predominantly white club serious. Imagine a book club full of well-off white women, nursing glasses of Pinot and plates of banana bread, the prototypical American book club: It doesn’t seem like the prime setting for harsh callouts. “In our dominant white culture, conflict, disagreement, the feeling of discomfort, those are all really unusual things to happen in a book club,” Humphries said. “And I think there needs to be room for those things in this kind of book club.”

Though Jewell said she hoped white anti-racist reading groups could stay on task and avoid becoming an unchallenging space for members, she expressed skepticism that this would be the case. “I’m not sure this is what is happening,” she said. “I have noticed how quickly the stamina of a lot of white people who seemed fully outraged in early June has waned.”

Morris, the founder of Black Men Read, suggested that having Black people present was important to counter the drift into ease. “What I caution folks to do, if white people are going to be putting together book clubs to read books about Black stories: Don’t get caught in your bubble,” Morris said. He suggested inviting Black friends to offer their perspective, and not requiring them to complete the reading. “A white-only group, it just satisfies your comfort level.”

There’s no one simple answer, however, to this problem. While inviting Black friends may prevent white people from lapsing into mutual reassurance, it also demands a great deal from those Black friends ― as does, as Rachel Charlene Lewis argued in Bitch, asking Black people for reading recommendations and tips for one’s book club. Bruce-Eddings noted that she was glad to see white people “place the onus of this education and radicalization on themselves, rather than reach out to the Black people in their lives for hand-holding and emotional excavation for the sake of their guilt.” She added, “I understand the intent, but it does more damage than they realize.”

For Dearing and Kriegstein Jacobson, the latter concern was front of mind. “Kate and I have talked a lot about not wanting to put that educational burden on someone who is living this every day. It doesn’t feel right,” Kriegstein Jacobson said. “I wouldn’t want to bring a Black person or BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, or other people of color] person into this space this early on. Personally I feel like we are way too novice and clumsy. We’re like a toddler that’s running around the house and falling down and breaking shit.”

In their group, they said, they’re trying to cultivate an ethos of resisting white fragility and calling each other out. “My hope for this was that we hold each other accountable in this group,” Dearing said. “I think there is that desire. I’m sure we will still, in our whiteness, miss things.”

A firm structure can help maintain focus, and resources abound for groups who want to guard against attention drift. Humphries suggested that groups studying independently should find a curriculum to follow. Hecht’s “Me and White Supremacy” Zoom discussion group follows the text’s suggestion of using the Circle Way method (including assigning members to roles like “scribe” and “guardian”) to keep discussions on track. “There isn’t chitchat about our lives,” she said. “Some fragility has maybe come up, and it’s had to get dealt with, and it’s taken very seriously.”

But no matter how well-intentioned or determined, “white people cannot hold each other accountable for ending white supremacy,” Fleming said. “This is something that requires a shift of power relation.” For white people looking for genuine growth and accountability around racial justice, she argued, it’s vital to seek out guidance and teaching from Black communities and communities of color. Seeking that guidance ethically may be a daunting task, but she suggested getting involved with or taking cues from existing groups for white people involved in antiracism, like SURJ, to learn how to appropriately approach and compensate speakers and educators who are Black and people of color.

“SURJ develops these really deep and powerful relationships of accountability with organizations that are led by people of color. Our chapter has like 16 organizations that really set our agenda,” Humphries explained. “I think there is a pattern around which kind of study groups are really radical and transformative, that is connected to the way that those groups are happening in the setting of an organization or some kind of organized movement space.”

Joining a local organization with ties like this, she said, can make sure readers are held accountable — not just for what they say during meetings, but for how they channel their study into action.

The study and action program at SURJ Bay Area, as indicated by its name, is intentionally structured to integrate hands-on work into the conversation. Each meeting follows a “three-part framework for personal transformation that draws on your heart, your head and your hand,” Humphries said. In addition to exploring a deep spiritual and emotional response to the reading, and to intellectual discussion of what they’re learning, each meeting the members discuss future action they can take and check in on whether they followed through on past commitments.

“I think what feels different about just starting a book club amongst friends, is it feels disconnected from the hand work that is already happening in a local area,” cautioned Humphries. “Especially because I do think that there is a cultural tendency amongst white people to stay up in our heads about things, to really only do the head piece of the work. It does help to be in the context of a movement to help move you toward a heart and a hand piece.”

Political work has to be grounded in our humanity, otherwise it’s simply hypothetical; meaningless.

Carla Bruce-Eddings

Those solitary study groups may provide some shared motivation to take action, however. “The woman who invited me to the group, she was like, I feel like we need to use our Karen power to do something,” Mang said. “We don’t know what it is. We know we have this power. And we know we need to use it.”

At their best, anti-racist book clubs can push members to think of ways to help — and to actually show up — instead of turning into solipsistic self-help circles.

“If you have time to read, you’re probably in a decent space in your life,” Morris said. “So what I’m trying to push the guys to do is for us to continue to do what we can with the power we have, the success that we’ve had in life, to leverage our positions to help bring other people up.”

At Black Men Read’s emergency meeting, they discussed how members of different generations and backgrounds felt inspired to pitch in, and Morris took notes on the resources and ideas that came out of it to send to all the club’s members: a list of Georgia state representatives to contact, a Black gun organization for those who want to responsibly get a firearm. “Everyone has to move the needle in their own way,” he said.

The white book clubbers buying up anti-racism manuals, meanwhile, are at least hearing the message that reading books does not count as doing the work.

“What we are learning from everything we’re reading is that you can’t be anti-racist devoid of action. You just kind of can’t be,” said Kriegstein Jacobson. “If you want to call yourself an anti-racist, it must include action with impact. Intention counts for very little.”

Their group has become a space to share organizations that need donations or initiatives that could use a set of hands — and having like-minded people to volunteer and protest with can make getting involved look less intimidating and more sustainable.

“You’re connecting people who have never been politically active to people who have been politically active before,” said Mang, who had her own awakening after the 2016 election. The newcomers hear about their friends calling members of Congress, attending protests, and speaking up at city council meetings. “You influence them to do those things too. Things they want to do, but feel shy.”

The book club itself, the people I spoke to emphasized, is not a wormhole into an antiracist future or a tool for easing one’s own guilt, nor is it a version of doing the work. Though there are pitfalls that are important to avoid in creating and running such a group, the most central is ensuring that the book club doesn’t become a cul de sac for activist urges.

“Books are a great way to begin a journey,” Jewell said. “They should not be the end goal.”

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link