[ad_1]

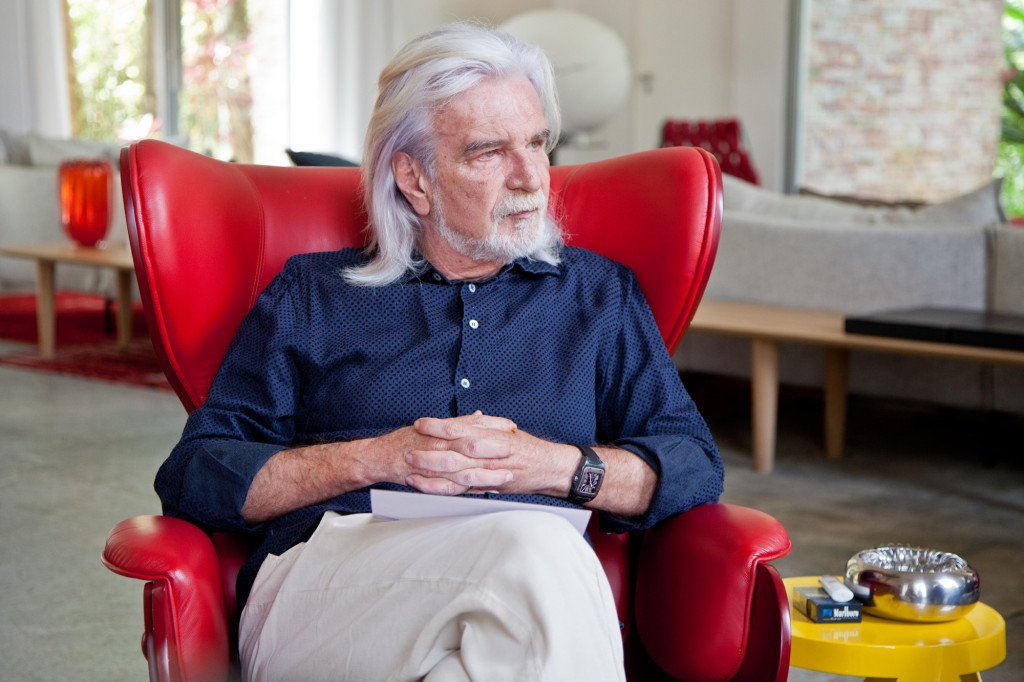

After more than two years, in what was perhaps one of the most shocking decisions in a criminal case to roil the Brazilian contemporary art scene, that ruling has been reversed. Earlier this month, a federal appeals court in the capital city of Brasília handed down a unanimous decision that Bernardo Paz, the eccentric collector who built the Instituto Inhotim, a massive sculpture park that reads as a who’s who of international contemporary art, has been cleared of charges in a money laundering case.

In November 2017, a lower federal court in Belo Horizonte sentenced Paz—who ranked on the ARTnews Top 200 Collectors list from 2002 to 2017—to jail for nine years and three months for money laundering related to Inhotim, after charges brought forth in a criminal complaint by the Ministério Público Federal, Brazil’s federal prosecutors. Paz’s sister, Virgínia de Mello Paz, was also convicted and sentenced to five years. The new ruling also acquitted her.

In the complaint, the MPF alleged that between 2007 and 2008 an investment fund named Flamingo transferred $98.5 million to a company called Horizonte, which Paz had set up to benefit the nonprofit Instituto Inhotim. The suit said that money was actually being used to pay expenses and debts for Paz’s businesses, including some 30 mining-related companies, rather than to support the museum.

In a statement sent to ARTnews on February 27, Paz said, “I’m glad the truth came out and for being officially exonerated. Now I hope to be able to focus my attention exclusively on my companies and on art, which is what really matters to me.”

Paz made a name for himself as a voracious collector of contemporary art in the early 2000s, buying up large-scale works for Inhotim’s sprawling 700-acre campus in Brumadinho that mixes contemporary art with various nature preserves and imported flora. After Inhotim opened to the public in 2006, Paz also began commissioning artists to make work, and he hired high-profile advisers including Allan Schwartzman, the chairman of Sotheby’s fine art division who also is Inhotim’s creative director and chief curator.

The collection includes major installations by Chris Burden, Doug Aitken, Matthew Barney, Olafur Eliasson, Robert Irwin, and David Lamelas, as well as a large collection by Brazilian artists, including Tunga, Lygia Pape, Hélio Oiticica, Cildo Meireles, Valeska Soares, Rivane Neuenschwander, and his ex-wife Adriana Varejão, among others. Later this year, Inhotim is slated to open a new pavilion by Yayoi Kusama.

Shortly after the ruling, other allegations surfaced regarding Paz’s mining companies’ business practices—including claims of child labor—and in May 2018, Paz resigned from the governing board of Inhotim. Though he was still the owner of much of the collection, Paz had struck a deal with the state government of Minas Gerais that saw the ownership of 20 works, including one by Barney and an earlier Kusama work, to the state, according to a report in the Art Newspaper. Because of Inhotim’s attraction as a tourist destination, the deal stipulated that the works could not be moved or sold, and that Inhotim was responsible for their upkeep.

In an interview earlier this month with the Brazilian daily newspaper O Estadão de S. Paulo, Paz said, “I suffered a lot, my family also suffered. After two years of depression, ashamed to leave the house, I see the light at the end of the tunnel.” When asked if he had plans to return to Inhotim, Paz said it was “too early to say anything.” (Per Brazilian law, Paz didn’t actually have to go to jail since the conviction was for a white-collar crime; he didn’t have to serve time until it was upheld by second court ruling.)

Though the MPF can still technically appeal the decision, Paz said he thought it was unlikely, pointing to the fact that the decision was unanimous and that an appeal would be virtually unprecedented. (The MPF has not announced if they will appeal or not.)

In a report about the new ruling, Paz’s lawyer Marcelo Leonardo told O Estadão that the logic in the complaint didn’t make legal sense, as the justification that the laundering occurred through a criminal organization wasn’t part of Brazilian law until 2013, and the alleged wrongdoing happened some six years prior. Leonardo added, “Justice was done.”

Update: February 27, 2020, 5: 20 p.m.: This post has been updated to include a statement from Bernardo Paz.

[ad_2]

Source link