[ad_1]

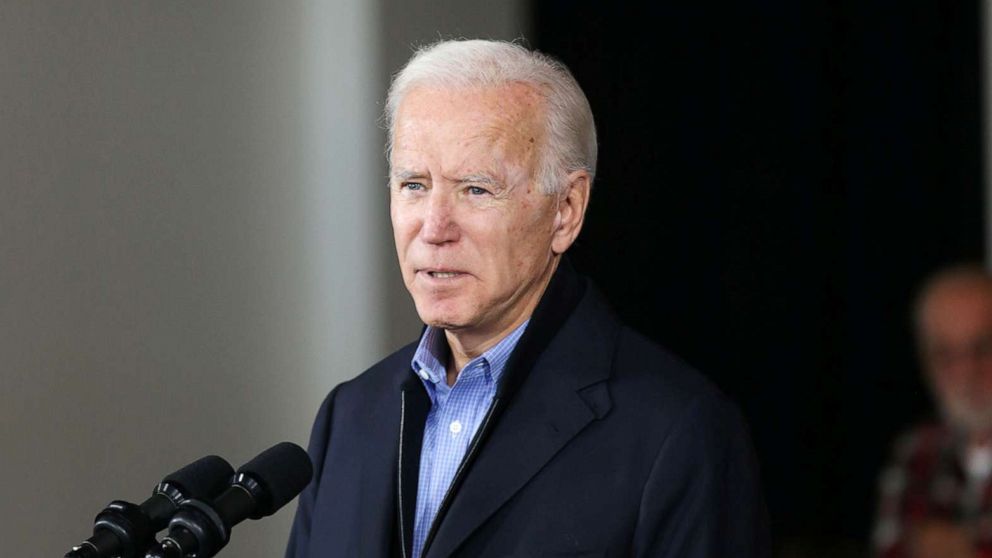

Two months before a Ukrainian official’s explosive claims about former Vice President Joe Biden were brought to President Donald Trump’s personal attorney, Rudy Giuliani, the since-disputed allegations about Biden corruptly trying to protect his son were pitched to a Washington lobbyist with ties to the Trump administration and U.S. Justice Department, according to the lobbyist himself.

Interested in Impeachment Inquiry?

Add Impeachment Inquiry as an interest to stay up to date on the latest Impeachment Inquiry news, video, and analysis from ABC News.

“I’ve known about this stuff since September of 2018,” the lobbyist, Bud Cummins, told ABC News in an interview. “I don’t know when the president heard about it, but I bet it was a long time ago.”

The outreach to Cummins marks the first known instance of the anti-Biden allegations coming to America. And it further explains how an apparent smear campaign hatched overseas ended up metastasizing inside America.

Cummins, a former federal prosecutor and practicing attorney, was hired in September 2018 to connect Ukraine’s then-chief prosecutor, Yuriy Lutsenko, with “high level” U.S. authorities — whom Lutsenko hoped would review evidence he collected allegedly showing Biden’s corruption as vice president, Cummins said.

“I knew precious little about Ukrainian politics at that stage,” Cummins conceded, noting he later “picked up” that Lutsenko “may or may not be a credible guy.”

Nevertheless, Lutsenko brought his allegations to Giuliani — and Trump-friendly media — only after Cummins seemed unable to find a receptive audience in the U.S. law enforcement community, according to a timeline of events described by Cummins and Giuliani’s public statements.

Nearly a year later, Lutsenko’s allegations are now at the heart of a House impeachment inquiry, whose witnesses have refuted the allegations against Biden as baseless and accused Lutsenko of unleashing falsehoods to promote his own interests.

NurPhoto via Getty Images, FILE

NurPhoto via Getty Images, FILE

‘I had no clue’

In early 2018, several months before Cummins said he first heard about Lutsenko’s claims, Lutsenko had launched a personal campaign to push America’s then-ambassador to Ukraine, Marie Yovanovitch, out of office, according to testimony from witnesses in the impeachment inquiry.

Lutsenko came to believe that she “destroyed him” by refusing to publicly endorse him until he rooted out corruption within his own office and “ceased using his position for personal gain,” an embassy staffer, David Holmes, recently told lawmakers.

In her own testimony to Congress, Yovanovitch agreed that Lutsenko was “personally angry” with her for keeping her distance from him.

So “in retaliation, Mr. Lutsenko made a series of unsupported allegations against Ambassador Yovanovitch,” Holmes testified.

Lutsenko even sought help from two Soviet-born businessmen with ties to Giuliani, Igor Fruman and Lev Parnas, who then enlisted a Republican congressman to call for Yovanovitch’s removal in a private letter to the secretary of state, according to recent testimony.

Fruman and Parnas have since been arrested for alleged financial crimes tied to their efforts against Yovanovitch.

But five months after that letter, Yovanovitch remained in her post.

That’s apparently when Lutsenko’s allegations against Biden were added to the mix — and when one of Lutsenko’s associates approached Cummins.

Chris Kleponis/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Chris Kleponis/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Cummins is a partner at the Washington-based lobbying firm Avenue Strategies. He joined the firm in June 2017, after working on the “transition team” shepherding Trump and his administration into office.

During the 2016 presidential race, Cummins served as chairman of Trump’s campaign in Arkansas, his home state. And for five years under the George W. Bush administration, he served as U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Arkansas, until he was forced out in 2006 to make way for a former White House adviser.

That Justice Department experience is at least part of the reason why he was approached to handle Lutsenko’s allegations, Cummins said.

Cummins never actually spoke to Lutsenko. Instead, a Ukrainian-American and two Ukrainian nationals who heard about Cummins acted as “intermediaries,” representing not just Lutsenko but other Ukrainian officials who allegedly could corroborate Lutsenko’s claims, Cummins said.

“I had no clue” if the allegations were true, Cummins added, noting that he agreed to represent Lutsenko’s interests because the “intermediaries” promised “actual documentary evidence” and witnesses willing to share first-hand accounts.

At the time, Cummins had never even heard of Lutsenko, he said.

‘He was making things up’

Lutsenko’s allegations against Biden were largely based on actions Biden openly discussed: In 2016, as the Obama administration’s point man on Ukraine, Biden pressured the Ukrainian government to fire Lutsenko’s predecessor, Viktor Shokin.

Shokin was widely viewed as a problematic figure, compromised by his own corruption and his failure to prosecute any significant cases, according to recent testimony to Congress.

Shokin’s firing, however, came as Shokin was supposedly overseeing an investigation into the major gas company Burisma, which had added Biden’s son Hunter to its board two years earlier.

Brenna Norman/Reuters

Brenna Norman/Reuters

According to Lutsenko, Biden forced Shokin’s firing to protect his son — an allegation of corruption that went far beyond lingering questions over whether Biden’s work on Ukraine and his son’s work for Burisma created a conflict of interest. The new allegation also surpassed previous questions over allegedly suspicious payments to Biden’s son from countries engaging with Biden.

At the time Lutsenko’s allegation about Biden’s role in Shokin’s firing first surfaced, Lutsenko was starting to face a new threat: upcoming presidential elections in Ukraine, where a new administration could mean a new top prosecutor to take over his position.

“He was acting in a self-serving manner, frankly making things up, in order to appear important to the United States, because he wanted to save his job,” Trump’s special envoy to Ukraine, Kurt Volker, told lawmakers last month.

But at the time, Cummins said, he didn’t know what may have been motivating Lutsenko or the other Ukrainian officials working with him.

“I didn’t vet them (or their evidence) very much at all,” he said. “I thought that was the job of the Department of Justice.”

‘A little dismissive’

Cummins may not have known much about Lutsenko, but he knew federal prosecutors in Manhattan had recently convicted one of Hunter Biden’s former colleagues for running a million-dollar fraud scheme.

Though Biden’s son wasn’t implicated in the scheme, Cummins thought the Biden connection “might be a hook that would make” the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York pay attention to Lutsenko’s allegations, Cummins said.

In addition, Cummins and the U.S. attorney, Geoffrey Berman, had worked together on the Trump “transition team” after Trump’s election, Cummins said.

So in early October 2018, Cummins reached out to Berman, and in a brief phone conversation Cummins explained how Lutsenko and the other Ukrainian officials were willing to share their evidence of alleged Obama-era corruption, Cummins recalled.

Berman “was a little dismissive” on the phone, according to Cummins.

So, Cummins said, he followed-up with a series of emails, laying out the allegations in detail and trying to elicit any kind response — which never came.

Peter Foley/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Peter Foley/Bloomberg via Getty Images

‘The very best thing’

A month after Cummins received no response, Giuliani was first told about the allegations from Lutsenko and other Ukrainians, according to Giuliani’s public statements.

“They came to me through an American investigator and a Ukrainian-American whose name has not been mentioned yet,” he said in a recent interview. “Nobody knows who these two people are. I do.”

Asked whether the “intermediaries” who came to him were the same ones who then brought Lutsenko’s Biden-related allegations to Giuliani, Cummins said he didn’t know.

“He and I have never talked about who else he’s talked to, and I haven’t asked him,” Cummins said.

Cummins said he’s also never had contact with Parnas or Fruman, the two Giuliani associates who early on persuaded a congressman to write a letter calling for Yovanovitch’s removal. Parnas and Fruman were indicted last month by Berman’s office.

In January, Giuliani formally interviewed Lutsenko and Shokin, seeking to record their allegations and the evidence they claimed to have against Biden and Yovanovitch.

Giuliani also asked two Trump-friendly attorneys, Joe DiGenova and Victoria Toensing, to represent Lutsenko in the same way Cummins already had, according to public statements from DiGenova and Toensing.

“Rudy asked us to represent any of the Ukrainian whistleblowers who wanted to provide information to U.S. law enforcement about what they had heard and learned,” DiGenova recently told a radio station in Baltimore.

Eventually, Giuliani brought it all to Trump-friendly reporters.

“I deliberately shared my stuff with media because I didn’t want to give it to the FBI,” Giuliani said in a recent interview with ABC News. “The very best thing to do is to use the press.”

Without identifying Cummins, Giuliani has often appeared to cite Cummins’ early work to accuse the Justice Department of “thwarting” and “stone-walling” the Ukrainian officials.

Though Cummins remained in contact with the “intermediaries” for several months, he said he shut down his efforts once Giuliani thrust the matter into the public.

In the end, he said that he didn’t even bill the “intermediaries” for his work.

Lutsenko stepped down as Ukraine’s top prosecutor in August.

Win Mcnamee/Getty Images

Win Mcnamee/Getty Images

‘They can have it’

In a letter to Congress on Friday, Giuliani urged the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., to open an investigation into the “very real” crimes committed by Biden.

In recent impeachment hearings, current and former U.S. officials testified that the allegations against Biden were “not credible,” as Volker put it.

Still, in his Friday letter, Giuliani insisted three Ukrainians were willing to testify and provide evidence, noting that, “Some witnesses went even so far as to hire a lawyer (who) presented the United States Attorney’s office with their information.”

“Now,” Giuliani wrote, “(the lawyer) is willing to share with you his memoranda and e-mail.”

Cummins told ABC News that he is willing to respond to any subpoenas he receives, as long as he protects attorney-client privilege.

If lawmakers want the email he sent Berman in October 2018, Cummins said, “They can have it.”

Berman’s office declined to comment for this article. Recent efforts to reach Giuliani have been unsuccessful.

ABC News’ Aaron Katersky and Matthew Mosk contributed to this report.

[ad_2]

Source link