[ad_1]

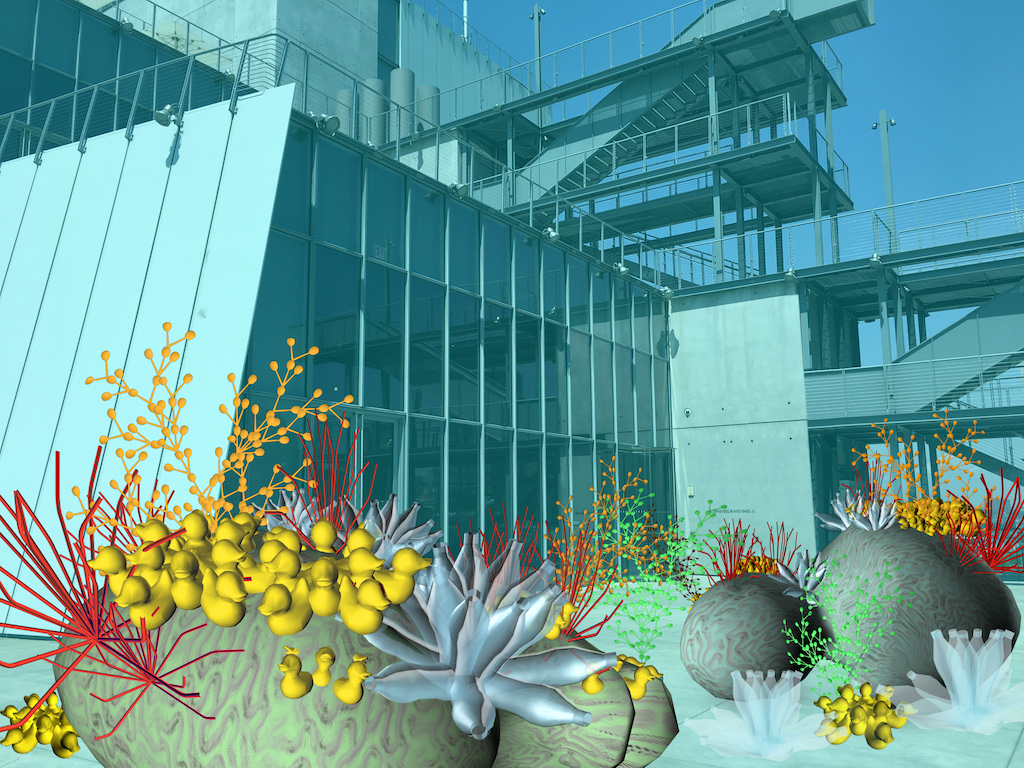

Tamiko Thiel (with /p), Unexpected Growth, 2018, augmented reality installation.

COMMISSIONED BY WHITNEY MUSEUM

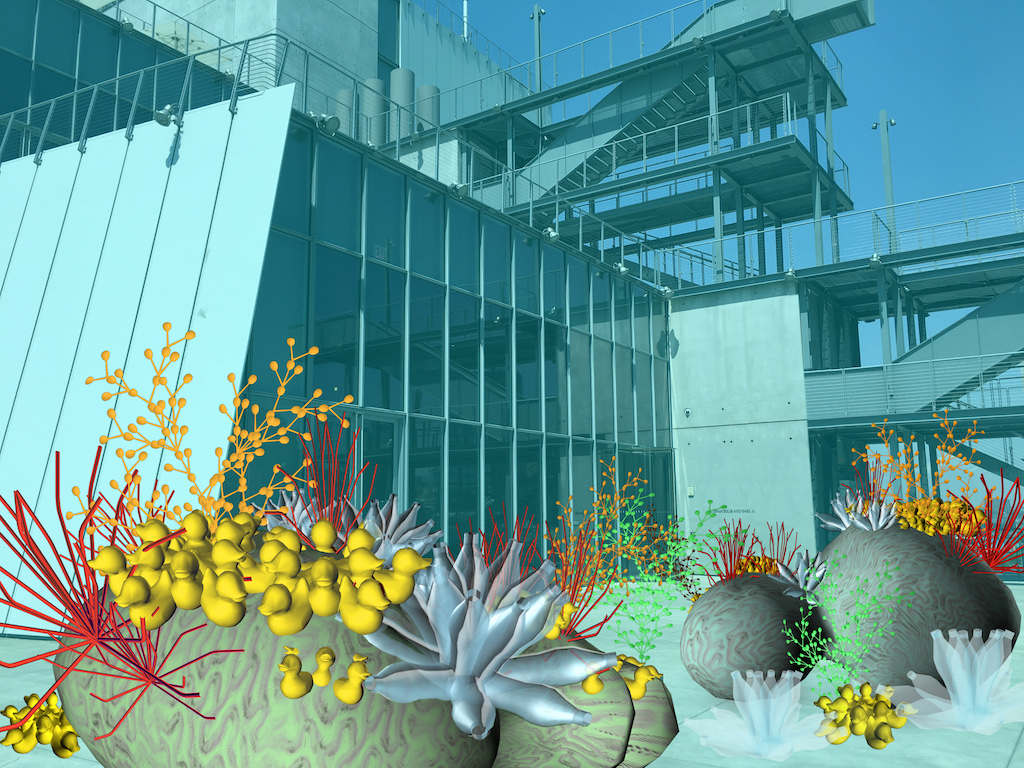

The Whitney Museum’s exhibition “Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965–2018” is noisy, chaotic, and strange, and the most radical museum show on view in New York right now. Curators Christiane Paul and Carol Mancusi-Ungaro manage to hit all today’s hot topics—algorithms, the flow of pictures online, and the politics that undergird the social media we use every day—while also doing something unusual for an exhibition of digital art: teasing out connections between it and pre-digital movements, in particular Minimalism.

“Programmed” (which is on view through April 14) is drawn mainly from the Whitney’s holdings, but it feels like more than a collection show. That’s one sign of good curating. Another is the fluidity with which the show toggles between early video art and cutting-edge digital work, between experimental dance and augmented reality, between text-based Conceptualism and technological-minded formalism. In one of the first galleries, a 1965 Donald Judd sculpture is shown alongside the roughly contemporaneous Charles Csuri piece Sine Curve Man (1967), in which a sitter’s portrait is rendered via an IBM computer, using data that warped its nose and mouth into a rippling mass of lines. The juxtaposition is a reminder that developments in technologically inclined art have always had something in common with what’s happening in traditional mediums like painting and sculpture. It’s a gesture well worth heeding, especially in a time when curators have a tendency to fetishize art about or involving technology.

Installation view of “Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965–2018,” 2018, at the Whitney Museum, New York.

RON AMSTUTZ

The show’s first half focuses on rules and systems, which were integral to Minimalism and Conceptualism during the ’60s and ’70s. Those movements sought to create artworks that were dictated entirely by sets of rubrics, with math often playing an important role, as it does in works here by Charles Gaines and Philip Glass. There has always been a technological dimension to such work, as evidenced by Sol LeWitt’s famous line, “The idea becomes a machine that makes the art.”

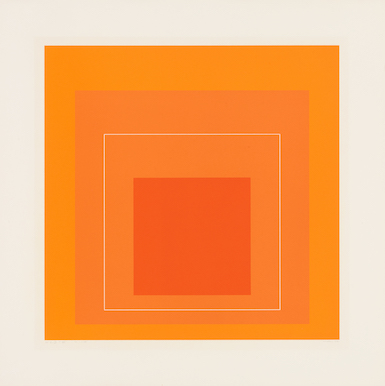

In LeWitt’s wall drawings, the Minimalist’s idea—recorded in the instructions he wrote for each piece—became a machine operated by whoever happened to be executing the work. In “Programmed,” a LeWitt wall drawing appears next to artist Casey Reas’s response to it: two abstract moving-image works that randomly reformulate themselves to create morphing seas of digital lines and curves, thanks to the software controlling them. Similarly expanding on LeWitt’s idea-as-machine are Rafaël Rozendaal and Mika Tajima, who transform sets of data into blocks of blue, red, and green through Jacquard-loom technology, and John F. Simon Jr., who rethinks Josef Albers’s experiments with perception and color theory through a software piece designed to produce faux modernist abstractions. These days computers can be programmed to do just about anything, maybe even be more original than their creators.

In a few cases, artists’ computers appear to have taken on a life of their own. Ian Cheng’s “live simulation” piece Baby feat. Ikaria (2013) features computer-generated debris that randomly comes together and flies apart; a wall text reveals that the digital bits are controlled by three online chatbots, who are conversing with each other via software Cheng has crafted as part of the piece. For Tamiko Thiel’s augmented reality work Unexpected Growth (2018), visitors use their iPhones and iPads to view a CGI coral reef that appears to expand and contract as different numbers of people use the technology. Cheng and Thiel’s pieces act as rejoinders to the M.O. of Minimalists like Judd, who engineered the instructions guiding the making of their works so minutely that nothing would be left to chance. These artists, on the other hand, merely provide a starting point, then let their creations run wild.

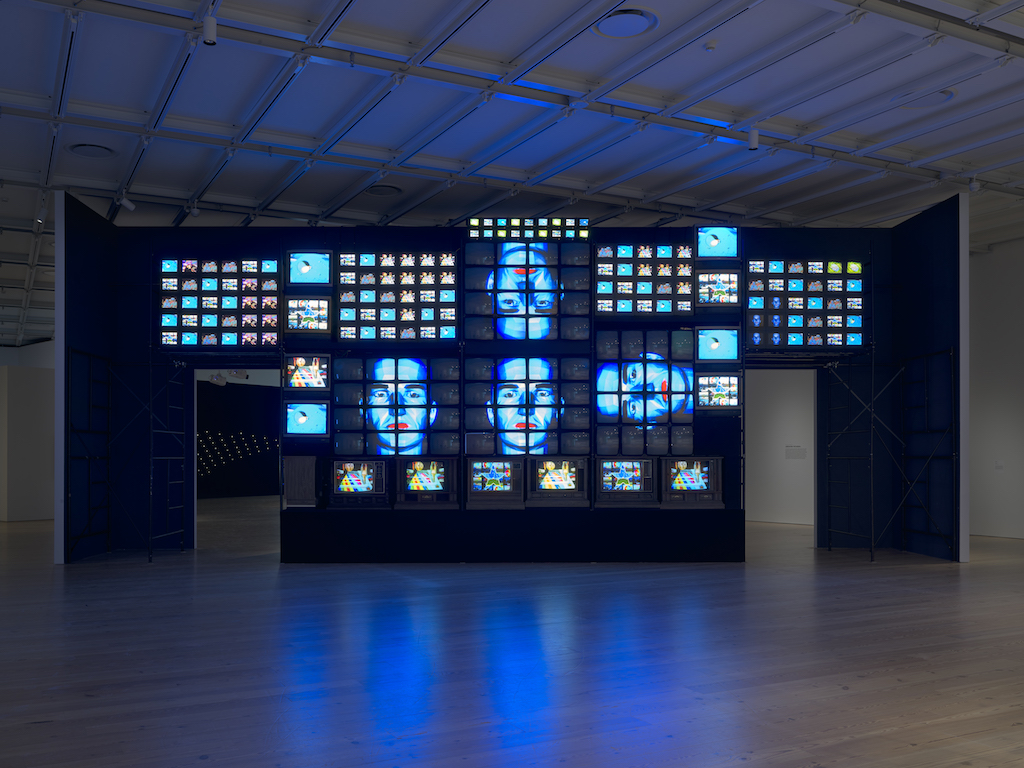

Nam June Paik, Fin de Siècle II, 1989 (partially restored, 2018), seven-channel video installation, 207 televisions, sound.

©NAM JUNE PAIK ESTATE/RON AMSTUTZ/WHITNEY MUSEUM, NEW YORK, GIFT OF LAILA AND THURSTON TWIGG-SMITH 93.139

The second half of “Programmed” shows how artists have reacted over the years to a world filled with streams of visual information—first televised images, then videos and pictures circulated online. Nam June Paik’s Fin de Siècle II (1989), a masterpiece lovingly restored by the Whitney, is the section’s centerpiece. It’s a grouping of 207 TV sets, all of them blaring at once in a riot of flickering images: David Bowie singing; Merce Cunningham dancing; a nude woman walking down some stairs (possibly an homage to Duchamp), her image repeatedly duplicating; a computer-generated cyborg head spewing nonsense. Produced the same year that the World Wide Web was made available to the larger public, the Paik piece—overwhelming, hypnotic, and a little terrifying—presages the flood of digital pictures that is now everyday life.

Some artists revel in the deluge. Siebren Versteeg offers two touch screens featuring a dense field of pictures—anatomical diagrams, stock photographs, advertisements—that can be browsed endlessly (perhaps a play on websites’ “infinite scroll”). Others subvert this one-way flow of visual information: Lynn Hershman Leeson tackles television’s misogyny with her installation Lorna (1979–84), in which viewers can control a choose-your-own-adventure-style video about an agoraphobic woman, and Cory Arcangel does something similar with his mellower piece Super Mario Cloud (2002), the result of hacking the eponymous video game to wipe out everything but the sky.

Josef Albers, White Line Square VI, 1966, from the portfolio “White Line Squares (Series I),” lithograph.

©2018 JOSEF AND ANNI ALBERS FOUNDATION/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/WHITNEY MUSEUM, NEW YORK, GIFT OF THE ARTIST 67.14.6

Putting televisual and digital works alongside one another may not seem revelatory now that so much TV is available online, but “Programmed” goes one step further by including artists who combine the two technologies. In Goethe’s Message to the New Negroes (2001), Paul Pfeiffer uses digital technology to mash together TV clips of basketball players mid-game. Pfeiffer has edited the piece so that, as the players shoot the ball, they appear to morph into one another, showing that what looks stable on a TV screen can break down when it’s fed into a computer.

Artists’ acts of translation—from analog to digital, from movie or TV screen to computer screen—can occasionally lead to misfires. Jim Campbell’s 2011 piece Tilted Plane, an installation featuring hanging light bulbs that render a film of birds flying a 3-D experience, feels like a silly experiment with expensive technology—better as an Instagram photo op than as an artwork. Nearby is Jonah Brucker-Cohen and Katherine Moriwaki’s America’s Got No Talent (2012 and 2018), an app that aggregates data on social media posts about reality TV series and takes the overly cute form of an American flag, a flimsy critique of this country’s obsession with spectacle.

More nuanced is Mendi + Keith Obadike’s brilliant piece The Interaction of Coloreds (2002 and 2018), which draws connections between whiteness, HTML coding, and Josef Albers’s color theory, and allows users to determine the correct coding for their skin tone by filling out a questionnaire. (The work can also be viewed online.) Albers’s prints based on his ideas—differently hued squares inset in one another—are included in the first half of “Programmed,” and his theories show up again here as a metaphor for the sets of information used to classify human beings. Though the Obadikes’s technology is ultra-new (the piece was even updated for the exhibition), it should come as no surprise that The Interaction of Coloreds invokes ideas more than half a century old. After all, as “Programmed” proposes, what’s old is always new again.

[ad_2]

Source link