[ad_1]

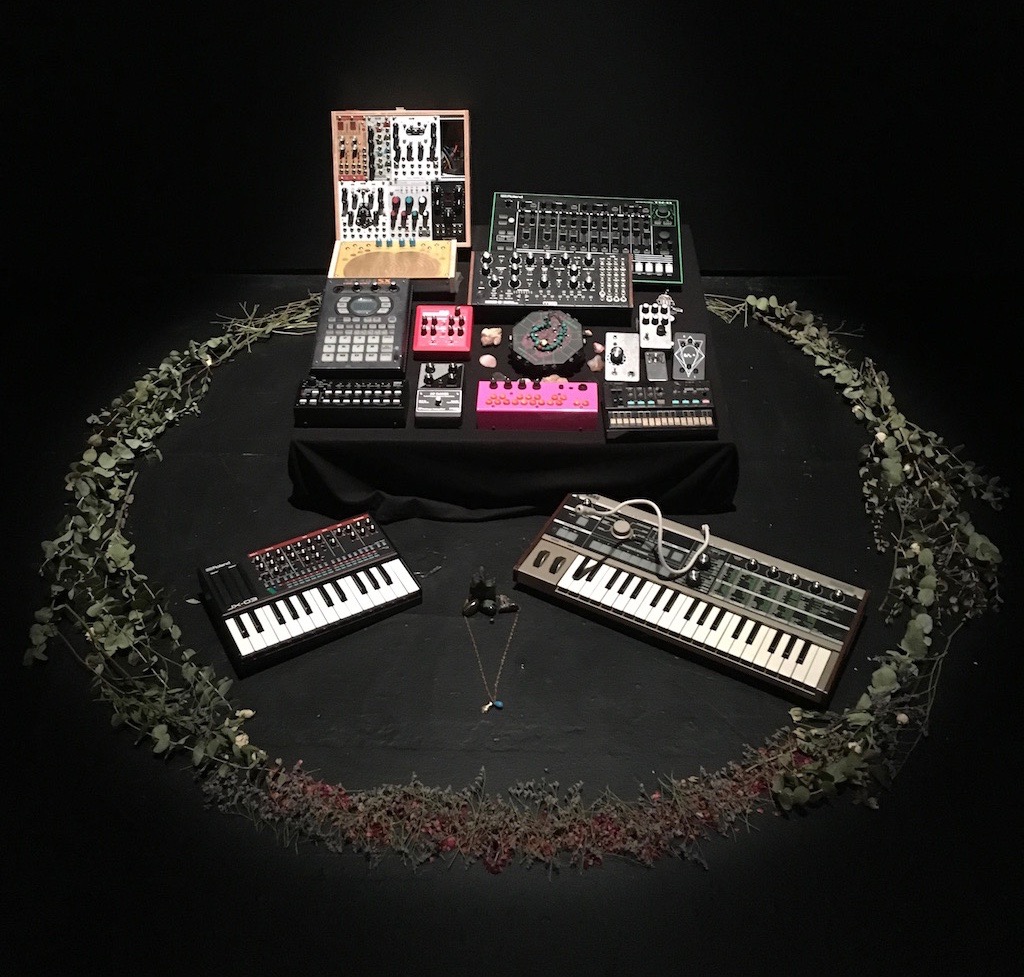

Camae Ayewa/Moor Mother, Synth Altar, 2018, at the Kitchen.

ANDY BATTAGLIA/ARTNEWS

For three weeks that moved much too fast, the upstairs gallery space at the Kitchen in New York played home to a curious kind of shrine. Surrounded by a circle of dried flowers and leaves, it consecrated not spiritual artifacts but a bank of electronic-music gear: keyboards, pedals, miniature drum machines, modules for analog synthesizer sounds. Then again, maybe they were spiritual artifacts for their master and arranger: the artist Camae Ayewa/Moor Mother.

That’s how she was billed—with her given name and her stage name conjoined—for “Analog Fluids of Sonic Black Holes,” a gut-punch of an exhibition that featured sounds of the Philadelphia-based artist’s making among videos, sculptures, poetry, and collages. The sounds were familiar to followers of the artier margins of electronic music, where Ayewa has commanded attention for searing, bracing, oftentimes wrenching minglings of distorted electronics with vocals that enlist whispered poetics and disquieting screams. But her lesser-known objects worked just as well to conjure troubled histories of racial discord and violent subjugation. “A lot of my ancestors are speaking through me,” she said last summer on a panel at the music-and-technology conference Moogfest, in reference to work that makes explicit reference to slave ships and lives lived in chains. The show at the Kitchen continued that haunting line of thought and followed it through an Afrofuturist trajectory.

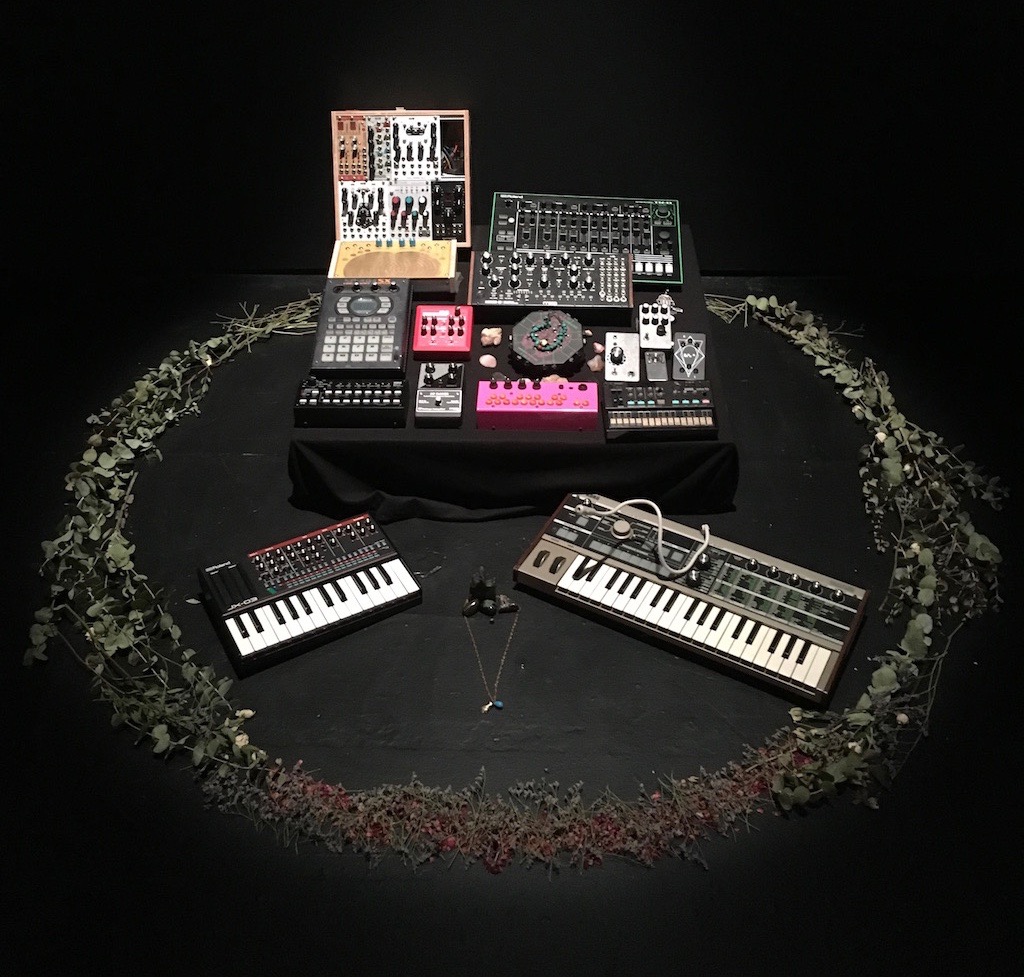

Collage work in a vitrine by Camae Ayewa/Moor Mother at the Kitchen.

ANDY BATTAGLIA/ARTNEWS

In a vitrine by the entryway, on a page labeled “Fetish Bones” (the name of a 2016 Moor Mother album well-worth hearing), words arranged as a poem read, “i was sure i was dead / in oakland / after being dragged by a pickup truck / in jasper / where 81 pieces of me/my body / was scattered across a back road.” Another page labeled “Irreversible Entanglements” (the name of a Moor Mother-affiliated jazz band also well-worth hearing) made reference to “a world where color is anti-black”—in which a “rainbow is met with a cohesive interference” and “a collapsing light is swallowing the lessons of the system.”

A projection on a large video screen of The Motionless Present 1 (2018) transmitted footage of Ayewa seemingly on the road as a musician, nearby display items like a book titled Project: Time Capsule by the duo Black Quantum Futurism (Ayewa is one of its members) and a collage featuring images of a saxophonist, a ceremonial mask, an astronaut, and a group of black men beneath a line of text reading “consciousness during astral projection.”

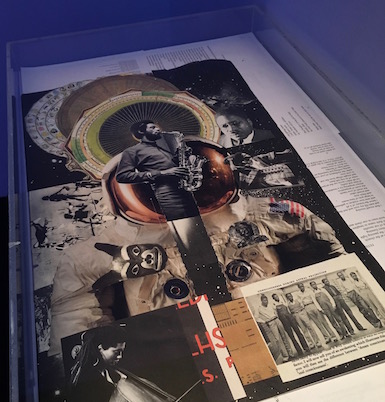

Past, present, and future blurred throughout the show. In the Kitchen’s main upstairs gallery space, more collage works evoked lineages moving both forward and backward in time, while presentations of music-playing devices—turntables spinning vinyl and Walkmen playing cassettes—filled headphones with signal-scrambling sounds by Moor Mother and Irreversible Entanglements. One video work showed Ayewa alone in a pastoral field, dancing around or otherwise sitting and flipping what seemed like tarot cards in front of electronic-music gear splayed out before her on the grass (not plugged into anything, powered perhaps by supernatural means). At one point, on screen, she put a large crystal in a trumpet and breathed deeply. Another video showed her playing machines covered with electrical tape and emblazoned with the words BRIGHT MUSIC FOR DARK TIMES.

Camae Ayewa/Moor Mother, The Motionless Present, 2018, at the Kitchen.

ANDY BATTAGLIA/ARTNEWS

Music of the sort took center stage in the Kitchen’s theater space two weeks ago, on one of what was supposed to have been two nights of live performances (the second night was cancelled due to snow). Accompanied by a trumpeter (Aquiles Navarro), bassist (Luke Stewart), and drummer (Tcheser Holmes), Moor Mother sat at a table, triggering sounds and turning knobs to work them into an aural brew while vocalizing into a microphone. Her messages, repeated like mantras, were spectral at the start: “he’s got the whole world in his hands,” “the flood’s coming,” “the idea of time and space has died.”

Then she got fiercer and more forthright in songs that played like hymns to the ghostly, post-slave-trade notion of the Black Atlantic, with words about bodies falling overboard from grim ships and sinking to a watery grave. Her words carried forth: “you’ve got to interact with light to make a shadow,” “this is the sound of us resisting,” “we still Emmett Till.” Toward the end, she posed a question: “I mean, what’s worse, man—you or me?”

[ad_2]

Source link