[ad_1]

David Wojnarowicz, A Fire in My Belly (still), 1986–87.

©THE ESTATE OF DAVID WOJNAROWICZ/COURTESY THE ESTATE OF DAVID WOJNAROWICZ AND P•P•O•W, NEW YORK

Throughout the 1980s, New York’s East Village was a hotbed for emerging artists, notably David Wojnarowicz, whose Whitney Museum retrospective opens today. The neighborhood’s artists were pioneers of a new style of queer art; not long after achieving recognition, many of them died during the height of the AIDS crisis. A sense of loss—of careers and lives cut short—is palpable in their work. As more and more of Wojnarowicz’s friends died of AIDS, and as U.S. government officials spoke out against obscenity in art, rather than working toward finding a cure for HIV, his paintings and photographs began to reflect the pain and trauma resulting from the disease. With the Whitney show in mind, below is a look at Wojnarowicz’s milieu, the critical reception of his work, and the influence it continues to have on artists today.

September 1983

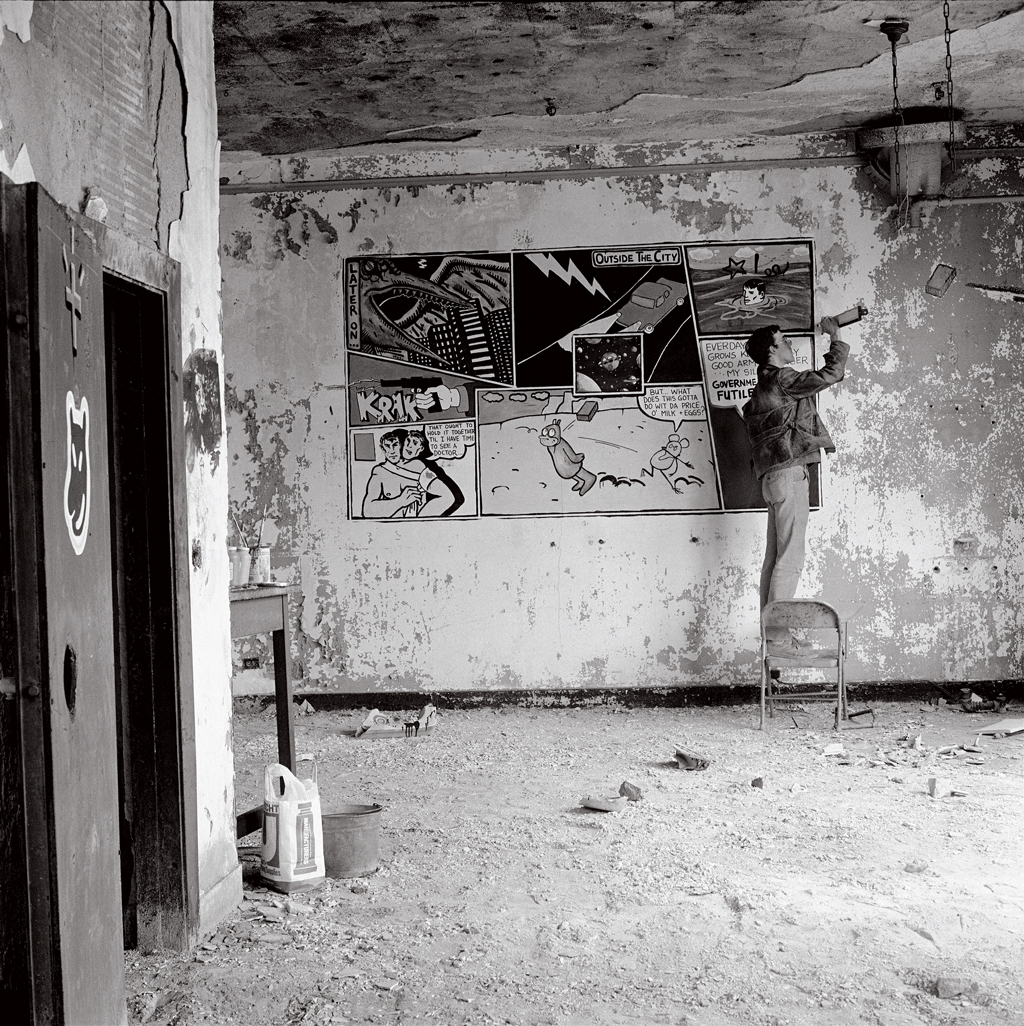

David Wojnarowicz, 28, began his career as a street artist noted for his lively spray-painted stencils of such objects as burning houses, fighter bombers and running infantrymen. After a brief spell with Milliken gallery in SoHo, Wojnarowicz is now back in the East Village, where he had a recent one-person show at Civilian Warfare. “The community between artists and gallery owners is much better on this side,” he says, comparing the East Village to SoHo. “It’s like working with your peers. Here there’s a lot more communication. People know each other.

—“Art in ‘Alphabetland,’ ” by David Hershkovits

Peter Hujar, Canal Street Piers: David Wojnarowicz working on Krazy Kat Comic on Wall, 1983.

©1987 THE PETER HUJAR ARCHIVE LLC/COURTESY PACE/MACGILL GALLERY, NEW YORK AND FRAENKEL GALLERY, SAN FRANCISCO

October 1983

In this show [at Civilian Warfare gallery], Wojnarowicz combines spray paint with acrylics on old garbage-can lids and supermarket posters that advertise specials, utilizing stenciled cartoonlike figures that often express violence. . . . The artist says he wants to illuminate the everyday violence that most people avoid and deny, a pattern he sees as destructive. However, the premise that urban dwellers generally repress awareness of surrounding dangers is questionable; furthermore, Wojnarowicz runs the risk of adding more agitation to an already violence-saturated environment.

—“David Wojnarowicz at Civilian Warfare,” by Lynn Zelevansky

January 1990

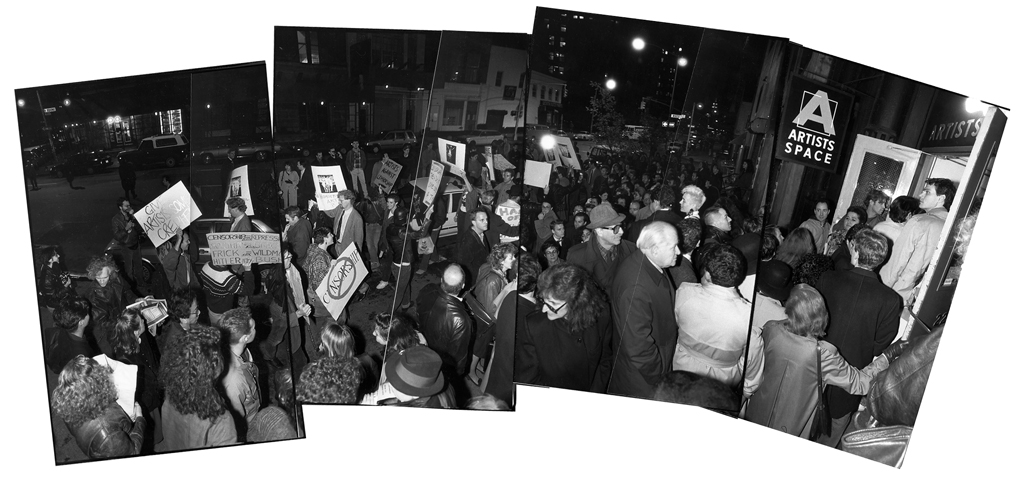

The recent face-off between John E. Frohnmayer, the newly appointed head of the National Endowment for the Arts, and Artists Space in New York, a long-established and respected alternative gallery, brought to a climax the controversy that began when congressional conservatives led by Senator Jesse Helms of North Carolina condemned the Endowment for funding art that they considered obscene or blasphemous. Spurred by anger at the Robert Mapplethorpe exhibition [at the Corcoran Gallery of Art], which included homoerotic and sadomasochistic images, and a photograph called Piss Christ by Andres Serrano of a plastic crucifix immersed in a jar of the artist’s urine, they legislated new guidelines that limit the Endowment’s grant-making policies. . . .

[The show “Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing” at Artists Space] deals with the devastating effect of AIDS on the art community and is accompanied by a highly political essay written by one of the artists in the show. After the new guidelines were passed, Susan Wyatt, executive director of Artists Space, asked the Endowment to amend [an NEA] grant so that it could be used to support the exhibition only, while a grant from the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation would pay for the catalogue. Frohnmayer instead withheld the grant because “what had been presented to the Endowment by the Artists Space application was an artistic exhibition. We find, however, in reviewing the material now to be exhibited, that a large portion of the content is political rather than artistic in nature.”

—“Caught in the Crossfire: Art and the NEA,” by Sylvia Hochfield

Demonstrations outside Artists Space during the opening of “Witnesses Against Our Vanishing,” 1989.

THOMAS MCGOVERN

January 2011

It was painful to watch the Smithsonian Institution twist itself in knots in early December, as officials tried to explain why it censored a video “in order to clear up a misunderstanding.” The misunderstanding ostensibly concerned an eleven-second scene of ants crawling over a crucifix in A Fire in My Belly (1986–87), by the late David Wojnarowicz. . . . While the Smithsonian said it stood behind the rest of the show, scheduled to run through February 13, others in the art world weren’t sure they should do the same. As the artist AA Bronson tried, unsuccessfully, to remove a portrait of his late lover from “Hide/Seek,” the cultural community debated some difficult questions: Are there any times when freedom of expression should be sacrificed for other goals? If so, was this really one of them? How could people protest [Smithsonian Secretary G. Wayne] Clough’s decision without penalizing the Portrait Gallery for doing a gay-themed show? Are the culture wars upon us? Now what?

—“Between a Cross and a Hard Place,” by Robin Cembalest

May 2014

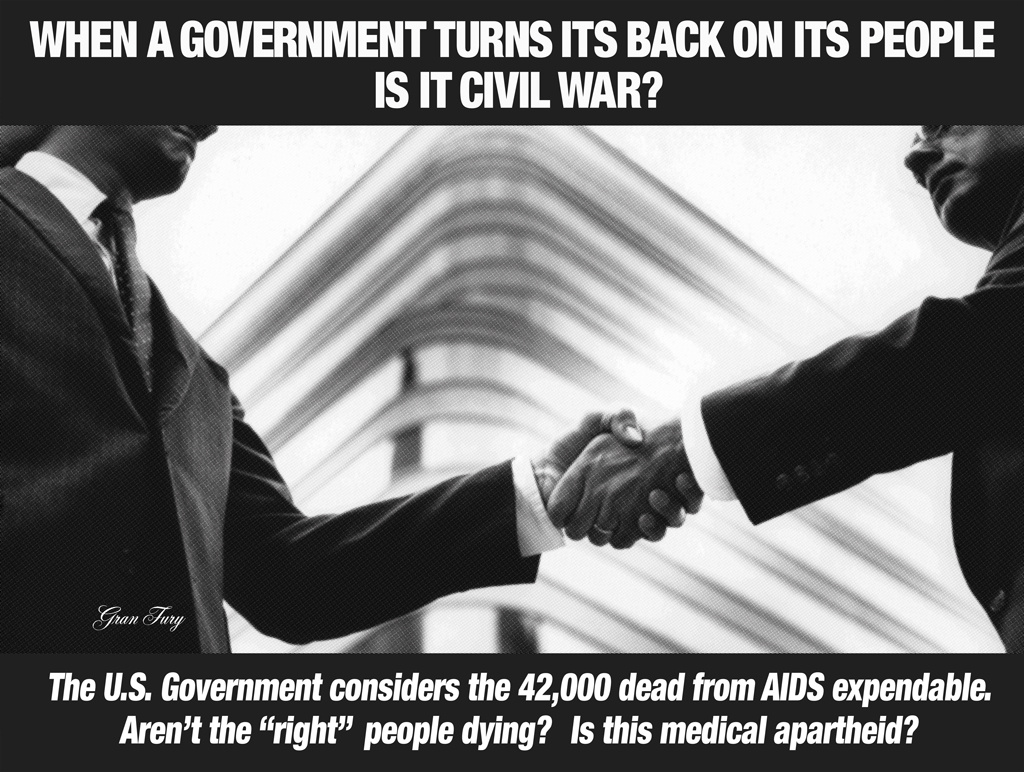

For much of the ’80s, many major institutions and critics ignored the AIDS crisis and viewed the activism of ACT UP and the public-art projects of artist collectives such as Gran Fury, General Idea, and Group Material as unnecessarily fueling the flames of the culture wars by drawing attention to the gay presence in the art world and directly attacking right-wing politicians. In fact, when art historian Douglas Crimp published an issue of October magazine devoted to AIDS and activism in 1987, he created a schism in the publication’s editorial board.

Now artists and curators are willing to concede that great art did come out of the anger, sorrow, and bafflement in the face of an epidemic, although few people would agree with [the] assessment that the AIDS crisis’s greatest impact was a transformation of contemporary art. “AIDS had an enormous impact on the culture, in the broadest sense of the word, not just the confines of contemporary art,” says [“From Media to Metaphor” co-curator] Robert Atkins, . . . “If we look at works from the 1990s and later half of the 20th century, we have to wonder, why is this work never conceptualized as a response to the AIDS crisis? Culture is a big thing, and AIDS was at the center of everything.”

—“Document, Protest, Memorial: AIDS in the Art World,” by Barbara Pollack

Gran Fury, When a Government Turns Its Back on Its People, 1988.

NGBK, WEST BERLIN, GERMANY

Sept. 18, 2015

To many, AIDS art is synonymous with AIDS activist art, such as the work by Gran Fury and others that was presented in the 2010 exhibition “Act Up New York: Activism, Art, and the AIDS Crisis, 1987–1993.” [Curator Jonathan] Katz’s [“Art AIDS America” exhibition] “is in some sense premised against that perception.” The exhibition’s animating conceit, he said, “is that much that hasn’t been identified as AIDS art is in fact AIDS art.” . . .

For Katz, those non-activist, non-blatant AIDS artworks constitute a larger historical irony. “The coding that an AIDS–informed body of artwork engaged replicated precisely the coding of queer art of the 1950s, when McCarthyism made equally impossible the articulation of identity. It’s very strange to see queer art come out of the closet and then go back in. And under AIDS [some of it] does precisely that.”

—“Is This the First AIDS Artwork?” by Sarah Douglas

Dec. 28, 2017

Two thematic exhibitions this year looked at the continuing influence of the AIDS crisis on the current era. . . . These exhibitions were a reminder of how people like [gender-bending performer] Hibiscus, who was almost completely lost to history, are kept alive by the memory of those who knew them. Later, the [Last Address Walk] took us to the city’s original AIDS memorial, which reads, “I can sail without wind, I can row without oars, but I cannot part from my friend without tears.” In times like these, may we not forget those who have been lost in our many struggles, and whose memory pushes us forward.

—“A Year in Queer” by Maximilíano Durón

A version of this story originally appeared in the Summer 2018 issue of ARTnews on page 111 under the title “As Wojnarowicz Is Our Witness.”

[ad_2]

Source link