[ad_1]

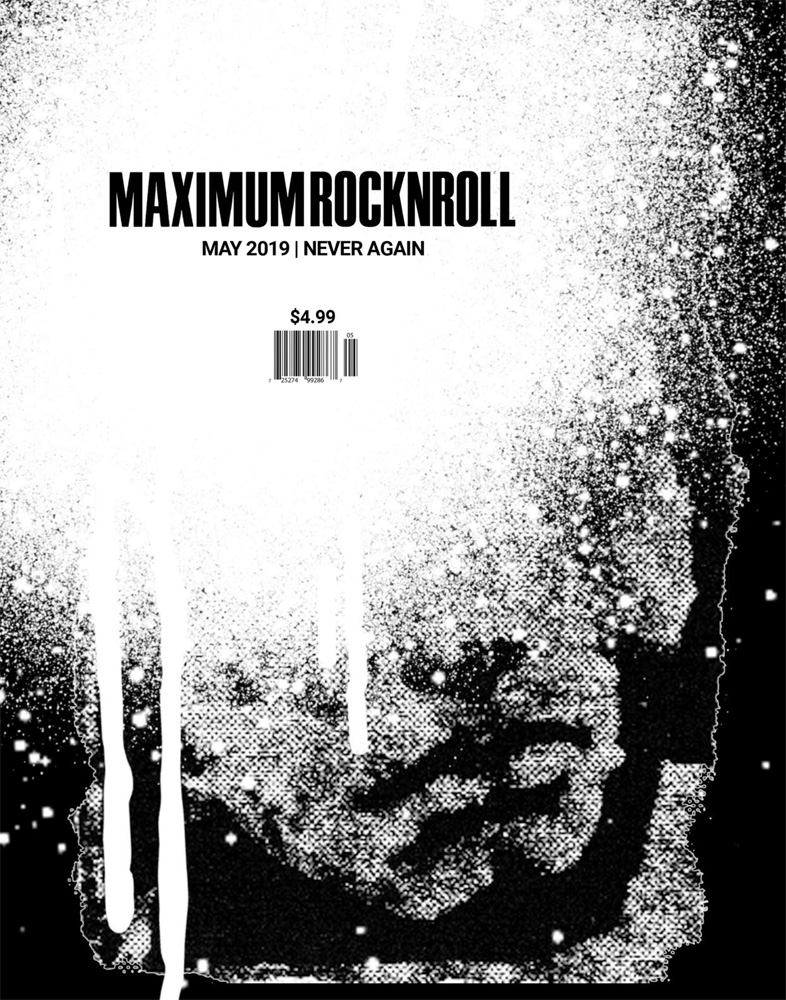

Cover of the final print issue of Maximum Rocknroll by Martin Sprouse.

For nearly four decades, the San Francisco–based publication Maximum Rocknroll has been a definitive monthly chronicle of punk and hardcore music globally, holding steadfast to a barebones aesthetic, anti-corporate ethos, and somewhat rigid musical policy, even as the larger media landscape has continued to mutate. In January, MRR announced the end of its run as a monthly print fanzine after 37 years, with the May 2019 issue of the magazine being its final physical outing.

According to Grace Ambrose, who from August 2014 until October 2017 served as one of the zine’s content coordinators (the magazine’s more democratic term for their team of editors), no one thing led to the shuttering of the print edition. Ambrose spoke of a “long-running accumulation” of factors including but not limited to the cost of living and rent in San Francisco, rising postage, and the decline of print media across the board. Maximum Rocknroll’s current San Francisco headquarters, which it has rented since 1992, was vacated in May. At the time of writing, the shape of its future physical space is still being determined. Meanwhile, an ongoing archival project dealing with digitizing the magazine’s back issues and cataloging its massive record collection (which is currently in storage) marches on. Much of Maximum’s most beloved content—record reviews, interviews—have gradually begun to move online.

A shift from print to the internet is just one way zine culture is morphing. The artist Jacob Ciocci, who read MRR casually in high school and whose 2000s-era art collective Paper Rad produced handmade zines as part of a larger body of multimedia work, told me about other changes he has witnessed. “We’ve definitely swung like 180, pretty much, for what a zine means,” Ciocci said. The artist recalled Paper Rad’s involvement in the 2004 Mobilivre Bookmobile project, a traveling zine show staged in a vintage airstream trailer, and compared that to a more recent experience interfacing with the more directly art world-adjacent New York Art Book Fair, where he appeared on a panel in 2014. “Our zines fell apart within three weeks of being on the bookmobile. They all literally fell apart,” Ciocci said, going on to compare “that level of craft versus this sort of tote-bag generation. How else do you describe it but the tote-bag generation?”

Within an increasingly-rarefied small press ecosystem, MRR stood apart; the publication’s signature non-aesthetic—black and white, printed on cheap newsprint—stayed consistent over multiple decades. “I think that Maximum doesn’t actually fit very nicely alongside the kind of bespoke, risographed, precious art books that you see at an art book fair,” Ambrose said, stating that MRR was always intended to be “printed on trashy paper and be a kind of disposable thing because it’s about the stuff that’s inside of it.”

MRR’s singular sensibility will continue with the magazine’s switch to internet-based coverage. “It’s important for us to remember that Maximum is not like [the online music media outlets] Pitchfork or Noisey or Stereogum in a different guise—it really is a totally different and unique thing,” Ambrose said.

Maximum Rocknroll was founded by Tim Yohannan, a veteran of the 1960s counterculture whose multigenerational experience within radical politics would come to influence the magazine’s overarching tone. In the late 1970s Yohannan started a punk radio show on the Berkeley public station KPFA with the name, and created the zine component in 1982, as a supplement to a compilation of music released on the East Bay label Alternative Tentacles. The ensuing decade would see MRR become a major source for everything punk, hardcore, and related, with columns that ran the gamut from irreverent to earnest and a reviews section that could read like a foreign language for those without the proper reference points. The magazine’s often-fractious letters section, too, became legendary: at times, it resembled a slower-moving version of the kind of discussions that have unfurled more recently on message boards and social media.

The magazine’s uncompromising vision came to a head in 1994, with the first of two major “purges,” which involved unloading parts of the magazine’s record collection and revamping its editorial policy, in the wake of the massive commercial success of punk-affiliated bands like Nirvana and Green Day. (The latter group was once a core member of the East Bay punk scene centered around MRR and the all-ages Berkley venue Gilman Street.) The moves cut all of the magazine’s connections to major label-related music. The second purge, which happened around the time of Yohannan’s death in 1998, was more abstract: it had to do with cutting certain strands of music that didn’t fit the founder’s narrow definition of punk.

From afar, Yohannan’s agenda could seem hardline, but a story told to me by the writer and musician George Tabb, whose involvement with the magazine spread over more than three decades, cast his politics in a different light. Sometime in the ‘90s, Tabb approached Yohannan seeking advice regarding a potential major label record deal offer his band had received. Yohannan told him to take it. “I’m like, the whole magazine, the whole thing is like: Don’t sign to majors,” Tabb said he told him in response. “And he was like, ‘That’s the utopian idea, but in the real world, if you want to make money with it, you gotta sign to a major.’ ”

With this in mind, Yohannan was perhaps attempting to use the magazine to create a conceptual, self-contained space in service of a specific position. When I was growing up, MRR played a role in a larger ecosystem of my music-media consumption, sitting alongside other scrappy, narrowcasted publications dedicated to electronic music, rap, and indie rock. Regardless of genre, many of these zines likely owed a debt to MRR’s pioneering DIY spirit, some more explicitly than others—the Bay Area rap magazine Murder Dog, for example, was created by a Sri Lankan immigrant with roots in punk rock. It had its first issue printed on the same press as MRR. Though their content coordinators have shifted on a regular basis, and though music-related information has continued to move away from the print sphere, MRR managed to produce a monthly magazine for over two decades following Yohannan’s death.

“When you think about things that the internet can replace, it makes sense that magazines would be one of the first things to start dwindling in popularity,” the artist Arvid Logan told me recently. As a teenager, Logan made a flyer for a concert at the New York punk venue ABC No Rio that appeared in an issue of Maximum Rocknroll. He is also the co-creator of the publication Dizzy with the curator and filmmaker Milah Libin. Though Logan and Libin are in their 20s and raised with the internet, the shifting nature of platform-based social media has laid bare to the duo the importance of a hard copy backup. “What’s nice about making something physical is that it can become an archive,” Libin said. “I feel like when I was younger there was this idea pumped into my head that anything you put on the internet, like you put it out there and it’s really hard to get rid of it,” Logan commented. “But the truth is, unless you’re a hacker, so much content on the internet is constantly disappearing.”

Taking one sort of long view, information housed primarily online can seem ephemeral. Johan Kugelberg, the founder of the New York–based archival company Boo-Hooray, who described himself as “patient zero” of Maximum Rocknroll, having read the first issue of the zine as a teenager in rural Sweden, told me, “Most historians I know who [think from] a historian’s perspective, which is three centuries, five centuries, ten centuries, they all see born-digital as hyper ephemeral because the moment you pull the plug out of the socket there’s nothing.

To that point, this March, a server migration error caused the social-media platform Myspace to lose all of the music uploaded to its website between 2003 and 2015, a staggering loss for all threads of contemporary music (a percentage of the music was recently recovered via an anonymous academic group). For some, Myspace served as a community incubator not unlike Maximum. Though organizations like Rhizome are working to find archival solutions in the digital space, the fact remains that when digital content has the ability to be lost forever, a 7-inch record or print fanzine can start to feel more and more practical.

Maximum Rockandroll’s 37 years of monthly print issues serve as a steady physical document chronicling a forever-changing underground. In the decades following Yohanan’s death, some of MRR’s old guard have departed, bemoaning a generational shift in the magazine, both musically and politically. To others, certain developments within the magazine have made it more inclusive—and appealing. Starting in 2006, the writer Osa Atoe created the zine Shotgun Seamstress as a way to address issues of race in punk. She also kept a column for MRR between 2009 and 2011. “Being black and into punk you’re basically pretty isolated on the basis of race within the scene or the community,” she said during a phone call. With her zine, she told me that “I think I was trying to normalize my identity as a black punk rocker to myself, like make myself comfortable with my own identity.”

Atoe told me that for a time she thought of MRR as a zine with a focus on strains of punk she was less interested in. “I feel like in more recent years, they’ve kind of diversified what they cover,” she said. “There’s a lot more people of color in it, a lot more queer people and women in it, and then a lot more post-punk and regular punk kind of bands. I feel like it became more my thing as time went on.”

Though the magazine has broadened its scope somewhat, Atoe told me she understood why there are still gates around broader punk culture. “I get why people just want something to mean something. They want punk to mean a specific thing,” she said. “And I get that, but then [that stance is] also annoying and bratty. But then that’s what punk is. It’s like a teenager.”

[ad_2]

Source link