[ad_1]

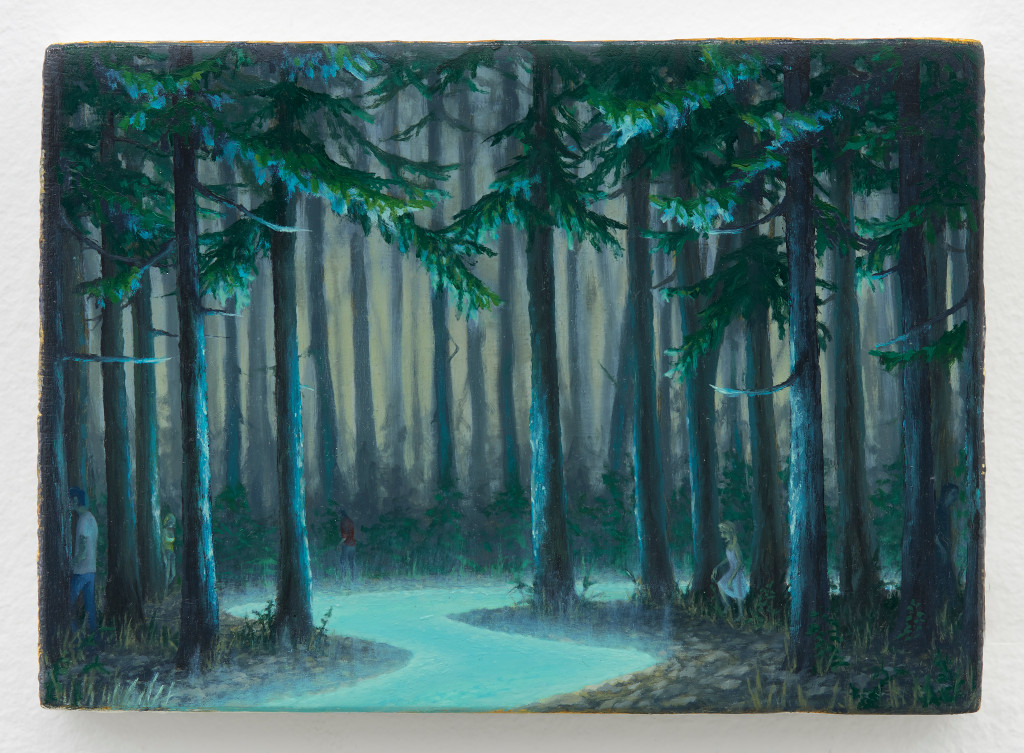

With his characteristic passion and sensitivity, Dan Attoe creates the kind of art that may represent a new understanding of life in the time of Covid-19. His solo show at the Hole gallery in New York—closed by the shutdown in the city and now open by appointment only—is named after Glowing River (2020), a paperback-sized oil painting featuring a slender blond girl wearing a white sundress who appears to be wandering toward a neon-blue stream like a plucky protagonist fighting through the magical wildness in a fairy tale. Her compelling form and apparent fascination with the supernatural water initially captures the viewer’s attention. But prolonged looking summons other characters to emerge warily around her. Casually dressed in contemporary clothes, those adults are atomized while interconnected, practicing social distancing but comprising a society.

This delicate painting, created with Attoe’s signature poignancy and poetry, highlights what we can’t overlook, as well as something we are now beginning to recognize—we need each other and we are all, for better or worse, in this together. It’s a theme echoed by Go Easy (2020), a wall-sized neon sculpture of a bouncy blond hovering over her own reflection in a lake between mountains. The work’s title sounds like the self-care mantras that have become commonplace in many people’s daily lives—it’s like a call for viewers to go easy on themselves. Weeks ago, this title seemed like a generous, optimist message. Now, it’s a powerful directive in a time when it’s just about impossible to avoid stressful situations.

Just days before New York began facing the full brunt of the coronavirus pandemic, Attoe sat down for an interview in the city. Creating art in Washougal, Washington, where he lives with his wife and daughters, Attoe offered insight into America’s myths and marrow. His words about creative expression in disastrous times now ring especially true.

ARTnews: What can art do in times of mass distress or crisis?

Dan Attoe: There are a few things that I think art can do. My favorite, and the one that applies to almost all art, is that it can give us psychological solutions and communicate coping mechanisms that have a healing effect. Another thing it can do, in a more ideological way, is make suggestions for sociological change that can occasionally unify people, as in work by Pussy Riot or the Guerrilla Girls or Barbara Kruger and as in countless protest songs through history. Finally, it can offer human contact through complex and sometimes intimate forms of communication—which can be medicinal to viewers.

Your show was developed and opened long before Covid-19 reached national consciousness, but the mantra “go easy on yourselves” seems especially necessary now. Diseases represent societal and physical distress. What inspired you to portray that message? What do you think Covid-19 and the resulting response says about us?

It’s hard to generalize here. I understand from biology and climate science that more viruses will be showing up, now that the temperature of the earth is increasing, so the virus itself isn’t a surprise. I think that if Trump and his administration had listened to and respected science, they would have had more warning that this was coming. I have a friend who was in China last fall, and he knew about this virus then. This administration’s views have set us back, and it’s indicative of a mindset of much of the country.

I think we could have been led to preemptive measures more calmly. I don’t know how easily that would have worked, though—it does seem like people tend not to worry about something until it directly effects them. I think that most of us are overwhelmed by so much information on a daily basis, we don’t know what to take seriously. This can hurt the dissemination of useful and grounded information.

Arturo Sanchez

Your work often speaks to some underlying tensions and prevailing currents in American society. In your work, is there some connection between your subjects and the American myth?

My work is rarely very direct, and if it is, it’s usually an accident. I pay attention to politics and culture as much as I can, and let it filter into my work through my own psychological process. However, because topical concerns have been so extreme in recent years, I see them finding their way into my work more. That thing in [the painting] Beached is some kind of injured abstract shape that looks like a whale, but isn’t really—it’s a big dark blob with light coming out of punctures. It feels like something that people don’t want to see injured, so the little figures on the beach are being drawn to it and touching it. It appeals to a deep need in me to see people coming together. I live in a rural place, and I see people getting more polarized, and I actually hear people talking about violence on ideological grounds. That dark blob does contain philosophical, ideological, and ecological meaning.

What inspired its form?

I remember seeing a National Geographic documentary on penguins and the melting ice in Antarctica, and some of the footage was of them fighting kind of violently in mud. The narrator explained that, as resources are being strained, the penguins are fighting with each other more. Of course, the implication was to anthropomorphize this onto human relations, and I think it’s been a deep part of my understanding ever since. Ideological extremes in our country seem more and more blatantly related to a strain on resources—limiting immigrants, creation of jobs and hopes to “spread the wealth.” Having been raised by a man with a degree in earth science, environmental concerns have always been pulling strings deep in my consciousness.

You’ve developed a more ethereal and gauzy aesthetic in some of your larger paintings. What does that softer technique express that’s different than your crisper and tighter narrative paintings?

The larger work is meant to evoke my neon sculptures in a simple and comical way—with an airbrushed glow and oil painted neon tubes in the center. I’ve always had ideas that don’t quite work as neon, because they need black, or drips, or some aspect of my touch. I see this work as being more for a party atmosphere, or a larger group of people, whereas the tighter paintings are more intimate.

You recently announced on Instagram that you’ve started doing tattoos as well. So much of your work speaks to loneliness and the profound importance of connection. Does giving people the opportunity to wear your work serve as some protective bond between you and them?

Yes, I recently finished my apprenticeship under an old friend and owner of a local tattoo shop out here in Washougal, Washington, and can officially and legally put my art on peoples’ skin! At the core of my work is an interest in finding new things. For most of the last 20 years, that’s meant having experiences, then coming back and working by myself in my studio to make intricate paintings and drawings. I’ve always seen collaboration as an integral part of this process too. I’ve had numerous collaborative projects over the years – most notably an annual get together with art group Paintallica. Making custom tattoos for people to be kept by them and displayed in an intimate way, on their bodies, is a new level of collaboration, with a broader demographic than I’ve worked with before, that I hope to use to better my studio work as well.

I think of tattooing as being able to reach a mostly new group of collectors, and I get to peek inside their heads a bit to come up with meaningful work…. This has made me reflect on my work through a different lens, and it has also made me realize that tattoos have always been an influence on my art, whether by way of album art and skateboard graphics, or directly through friends, my own collection and people I’ve known with tattoos.

Arturo Sanchez

I like how the show’s press release describes the beautiful blond in Go Easy as “emerging from the mountains like an angel—or stripper.” Your work always presents a lot of reverence and respect for women’s complexities and power.

Thank you for that read. I remember hearing Matt Groening talk about the family dynamic on The Simpsons once—how the women of the household are really the ones who have a grasp on the world and can get things done, and the men are bungling and destructive, but somehow necessary. I think I’ve always had a similar understanding, and it finds its way through my work. In their defense, the men in my work are also hard-working and earnest, but they’re vehicles for my own struggle to make sense of the world, so they often suffer.

And the women?

I’ve always thought of women as otherworldly and angelic and attractive. My mother was a huge influence on me early on—she’s a strong woman, and she raised three boys in very rugged parts of the rural U.S. She was an avid feminist in the ’60s and ’70s, to the point that she was present in the studio when Helen Reddy recorded [the 1972 hit song] “I Am Woman.” I grew up making fun of the brutish aspects of the cultures I lived in—the over-sexualization of women being one of those. I put my flag on the extreme left in rural and conservative-leaning parts of this country.

As an adult, those politics have become more subtle, as my humor has grown and my experiences have broadened. While my neons draw inspiration from beer signs where women are often scantily clad, I have to reconcile my own animal attraction to both the women and that medium.

Is the female figure in Go Easy a goddess, a pin-up model, or both?

I think of the woman emerging from the mountains as having her roots in beer signs and movie posters, but simultaneously having a mythological quality and otherworldly powers. In this conflict between culture, spirituality, and psychological and animal needs, she delivers her important message, which, to me, is about acceptance of who we and others are.

Was Go Easy designed as a reminder to us or to yourself?

This question might apply to all my work. I come up with a lot of ideas that are more personal and seem only useful to myself. Something only seems worth sharing when it reaches a certain tingle in my consciousness. This one reached that tingle, so I thought it might have meaning to others too.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and condensed.

[ad_2]

Source link