[ad_1]

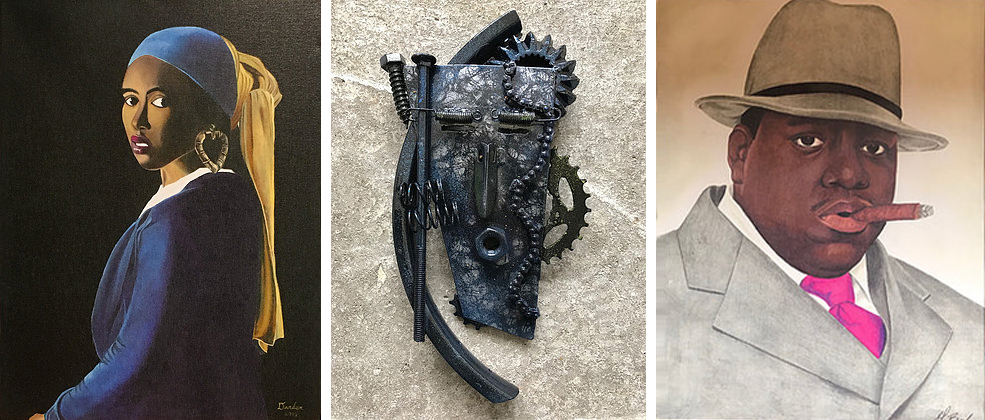

From left to right, Jay Darden’s Girl with a Bamboo Earring, Jeffrey Nelson’s Wall Sculpture, and G. Brock’s Biggie.

COURTESY ESCAPING TIME

On view on New York’s Governors Island now is art that shares a very particular provenance: the nation’s prison system. Assembled in an exhibition titled “Escaping Time: Art from U.S. Prisons” and supported by an organization with the same name, the work takes on different forms: paintings, drawings, sculpture, visions transmitted on repurposed bed sheets, and bits of old clothes. Variety also attends the artists themselves, some on the other side of their incarceration but most of whom will remain locked up for years or decades—even lifetimes—to come.

The program in its current incarnation dates back to 2014, when the first “Escaping Time” exhibition opened as part of an increasingly ambitious series of arts programming all over Governors Island. This year’s show takes up the whole of a once-grand and now intriguingly dilapidated house on the former Coast Guard base’s Colonels Row, with a changing array of works put on display and offered up for sale. Half of the proceeds—from works ranging in price from around $20 to $500—go to artists trying to make more work while making do with what they have.

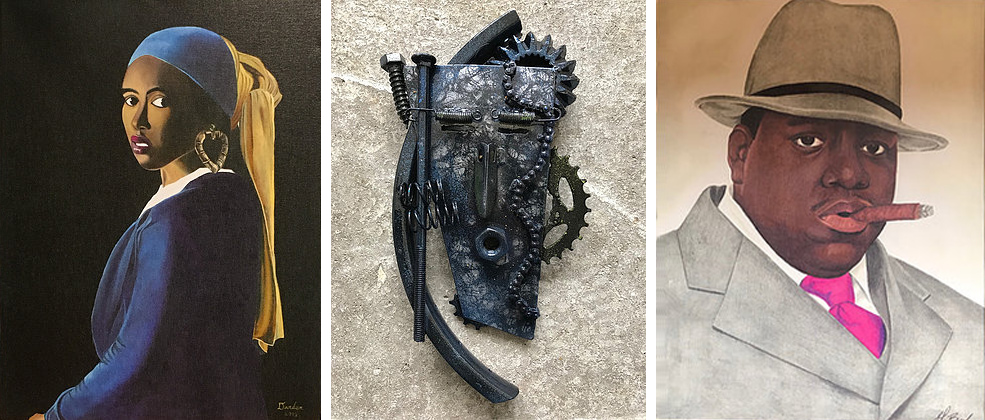

Jairo, Medusa, on ripped bedsheet.

COURTESY ESCAPING TIME

The program’s roots grow back to a time when Escaping Time’s founder, Mark Thivierge, a retired chief financial officer for an engineering firm and a longstanding art enthusiast, saw an exhibition at New York’s El Museo del Barrio that included paños—drawings made by prisoners on handkerchiefs or scavenged strips of cloth. “I was stunned by what people were doing in just pen and ink, prisoners who were totally untrained,” Thivierge said. “I thought, I could walk through Chelsea and not see work of this quality.”

While looking into the phenomenon, he came across a group working with incarcerated artists and conspired to put on a show. “The selection was based on my taste, but it was not just about the quality of the art,” he said of the criteria for inclusion. “Some of the messages were very graphic, and there was an intensity that was deep. These people were spilling their guts, basically. A lot of them were not pretty, and a lot of them never sold as a consequence.”

Nonetheless, Thivierge found himself stirred by the stories of the artists and what they were trying to express. “I wouldn’t call myself an activist, but I was moved by what was going on,” he said. “I wanted to keep doing it.”

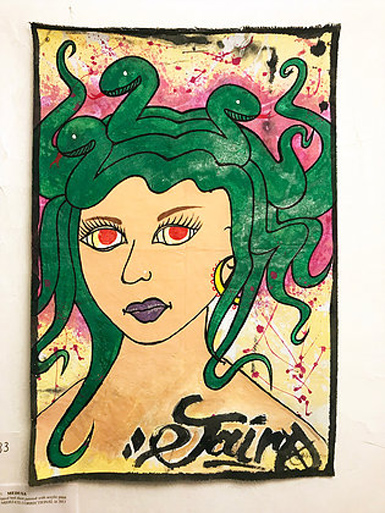

Mark B. Springer, My Corner of the World.

COURTESY ESCAPING TIME

The artists who work with Escaping Time have been imprisoned for a variety of crimes. One in the current show spent seven years on the notorious Rikers Island awaiting trial for a crime that prosecutors were conspicuously slow to bring to court—leading him to plead guilty to a crime he didn’t commit, Thivierge said. Another had consensual sex with a 17-year-old—a crime, clear and simple—but received a life sentence that some might deem as inhumane. “He’s been in there 17 years and has been assaulted to the point of hospitalization eight times,” Thivierge said. “When I met him, he was a total basket case, crying through the whole two and a half hours. Then he just started producing art. I don’t want to overstate what we’re doing, but I honestly feel like we’re saving this man’s life.”

Another artist is a convicted murderer who showed a capacity for delicate subject matter. “He would draw the most benign watercolors of birds,” Thivierge said. “You would swear it was right out of Audubon.” For that artist, Escaping Time abstains from sending direct payments, as it normally does, and funnels them instead to a battered women’s shelter that the artist chose as a beneficiary.

“Some of them are horrible people who absolutely belong in jail and should not be released,” Thivierge said of the artists he works with. “But there are a lot of people who have been given crazy sentences or plea-bargained because they had no choice.” In any case, he continued, “Our mission here is to educate the public about this population of people who are just anonymous numbers to everyone.”

‘It’s one thing to have work from people who are incarcerated, but it’s something else to have people who were incarcerated who can actually be here to talk to individuals who come through the exhibition.” So said Jay Darden, an artist (under the name J. Darden) who Thivierge brought on as a curator and figurehead for Escaping Time. “In the beginning, I was just someone who did time, learned how to paint, had some artwork, and was willing to put it up.”

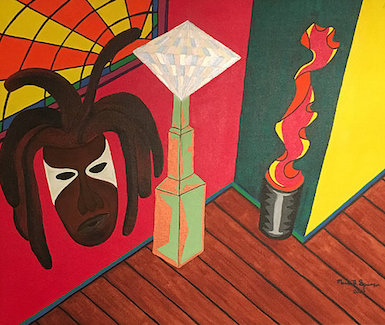

Chico Nelson, Colbie Callat.

COURTESY ESCAPING TIME

Darden first turned to painting while in jail in New Jersey. “I was able to get canvas and actual supplies—I was fortunate,” he said of a program that still ran into problems on occasion. “When I was released, the arts and crafts program was on hold because they had to determine what size of brush would be too long, where it could be considered a weapon.”

Learning to paint in prison can require thick skin. “Most of your education comes from the criticism of other inmates, who were happy to say, ‘You’re doing a nice job’—or ‘You’re not doing a nice job,” Darden laughed. “But because there are other guys who have done more time, you can ask them questions about blending colors, you know, or composition. You wouldn’t expect that in a prison, but it exists.”

Tips of the sort helped aid in the creation of Girl with a Bamboo Earring, a painting of Darden’s in the “Escaping Time” exhibition that alludes to Vermeer. (“I was working from a photograph and trying to figure out how to get the folds right in the scarf,” Darden said of that one.) Advice also aided artists in other prisons, such as the one-named Soden, who since being locked up in 1980 has focused largely on landscapes. “The thing he wants to see is the outside, nature,” Darden said. “He can go to the prison yard, where there are barbells and dirt. That’s not quite the same as seeing rivers and bridges and trees and whatnot.”

The sculptor Jeffrey Nelson has attained special status as a “trustee” inmate at the Louisiana State Penitentiary (a.k.a. Angola Prison) and thus has access to metal and torches to make his work. “This baffles a lot of visitors when they come through,” Darden said of the elaborate equipment needed to make masks with shaped machine parts.

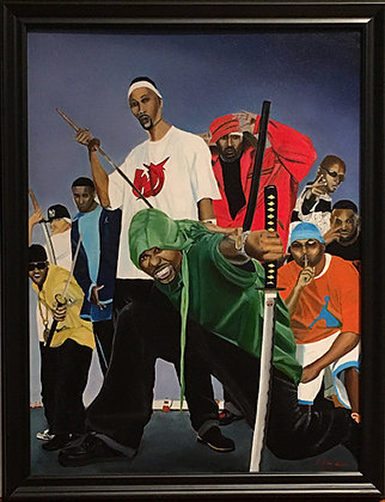

J. Darden, The Wu.

COURTESY ESCAPING TIME

Other artists in the show have been known to make flowers from toilet paper and wearable art of various kinds. And of course there is a lot of drawing and painting, such as work by a new artist on the Escaping Time roster: Chico Nelson. “The thing that strikes me about his work is the way he renders eyes,” Darden said. “There’s something about them I can’t put my finger on, but it’s so different from anyone else we have here.”

And then there are multiple works by Darden himself, including a striking group image of the Wu-Tang Clan, with swords swinging and the RZA in jeans that droop. “Someone came through last week and said, ‘What is this, a gang?’ ” Darden recalled. “I had to school him on ’90s hip-hop for a moment.”

The art in the Governors Island exhibition—on view through September 30—has cycled in and out as works have sold and made way for other pieces. And then there is always new work being made. “For a while it was us trying to reach out to other individuals,” Darden said, of outreach efforts that have proven effective. “Now individuals are reaching out to Escaping Time.”

[ad_2]

Source link