[ad_1]

With the biggest Marcel Duchamp survey ever held in Asia now on view at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Korea in Seoul, this week we turn back to the December 1968 issue of ARTnews, which featured an interview originally conducted by Francis Roberts in 1963, when the artist had a retrospective at the Pasadena Art Museum in California. The interview, which includes Duchamp’s musings on why he chose not to rely on film in his work and whether readymades could count as artworks, follows below in full. —Alex Greenberger

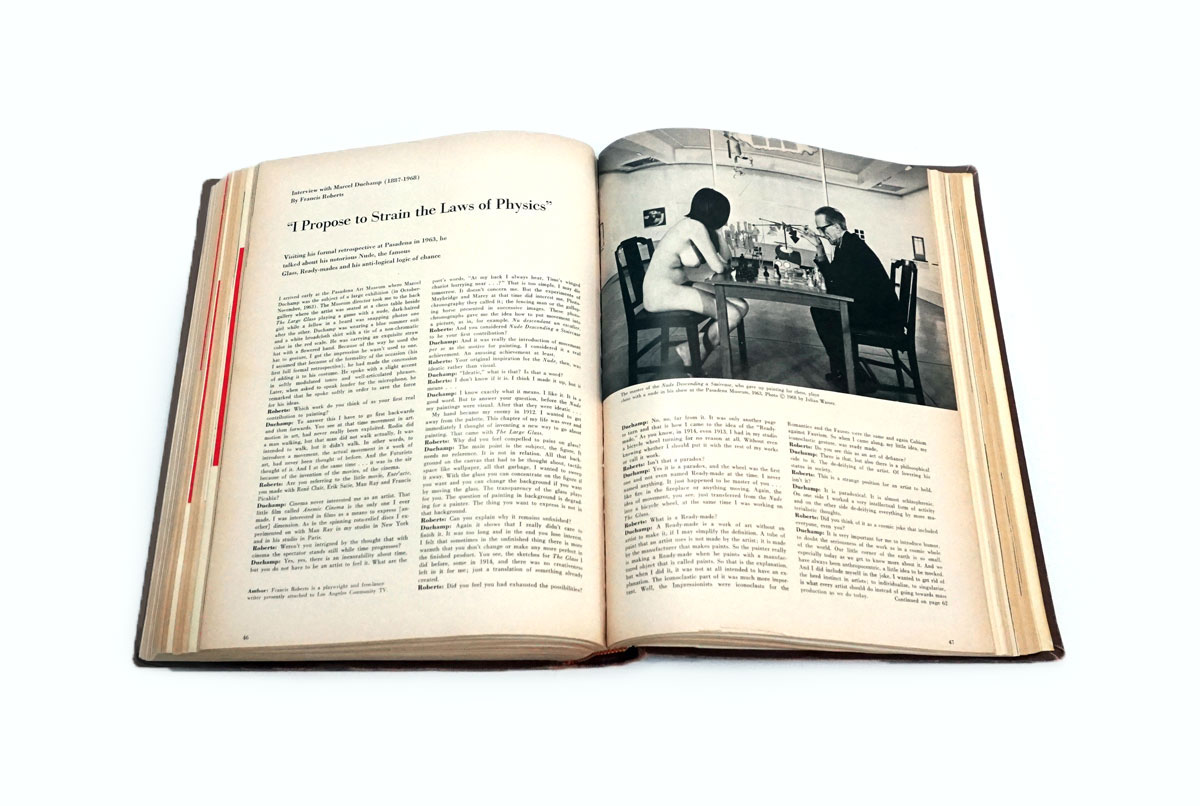

“ ‘I Propose to Strain the Laws of Physics’ ”

By Francis Roberts

December 1968

Visiting his formal retrospective in Pasadena in 1963, he talked about his notorious Nude, the famous Glass, Ready-mades and his anti-logical logic of chance

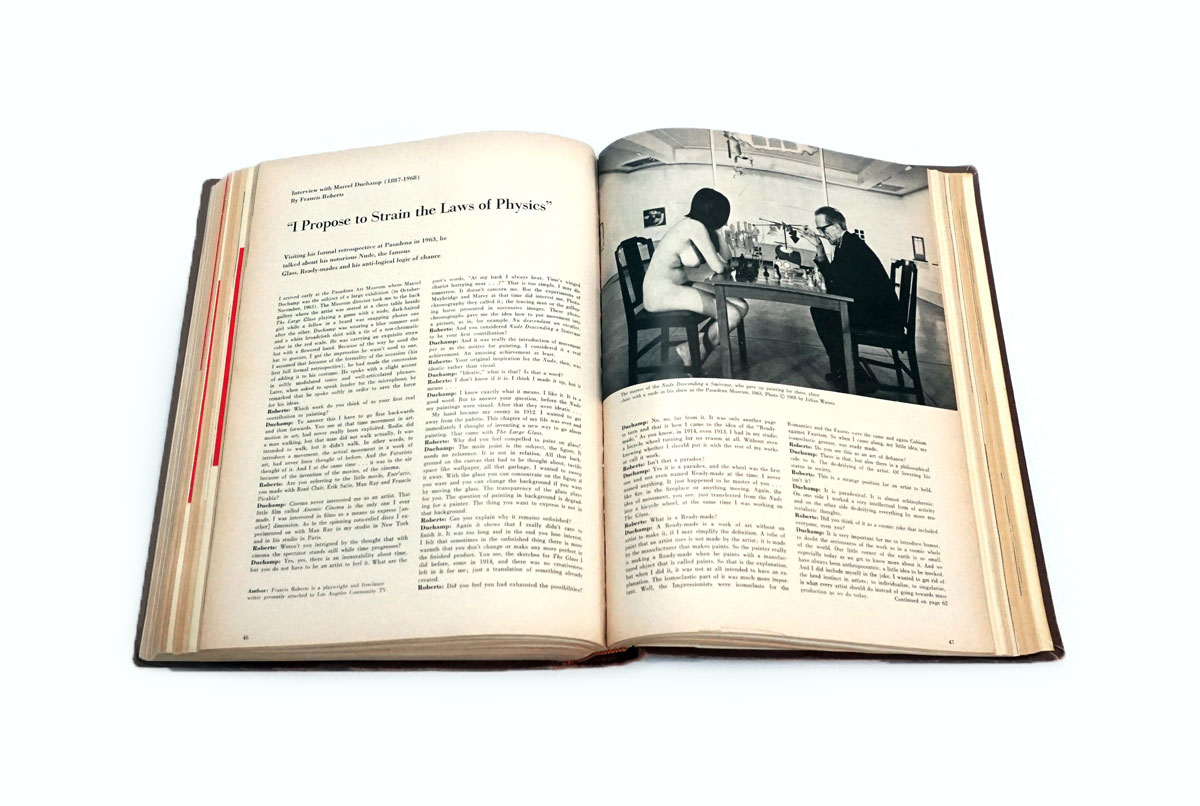

I arrived early at the Pasadena Art Museum where Marcel Duchamp was the subject of a large exhibition (in October-November, 1963). The Museum director took me to the back gallery where the artist was seated at a chess table beside The Large Glass playing a game with a nude, dark-haired girl while a fellow in a beard was snapping photos one after the other. Duchamp was wearing a blue summer shirt and a white broadcloth with a tie of non-chromatic color in the red scale. He was carrying an exquisite straw hat with a flowered band. Because of the way he used the hat to gesture, I got the impression he wasn’t used to one. I assumed that because of the formality of the occasion (his first full formal retrospective), he had made the concession of adding it to his costume. He spoke with a slight accent in softly modulated tones and well-articulated phrases. Later, when asked to speak louder for the microphone, he remarked that he spoke softly in order to save the force for his ideas.

Roberts: Which work do you think of as your first real contribution to painting?

Duchamp: To answer this I have to go first backwards and then forwards. You see at that time movement in art, motion in art, had never really been exploited. Rodin did a man walking, but that man did not walk actually. It was intended to walk, but it didn’t walk. In other words, to introduce a movement, the actual movement in a work of art, had never been thought of before. And the Futurists thought of it. And I at the same time . . . it was in the air because of the invention of movies, of the cinema.

Roberts: Are you referring to the little movie, Entr’acte, you made with René Clair, Erik Satie, Man Ray and Francis Picabia?

Duchamp: Cinema never interested me as an artist. That little film called Anemic Cinema is the only one I ever made. I was interested in films as a means to express [another] dimension. As in the spinning roto-relief discs I experimented on with Man Ray in my studio in New York and in his studio in Paris.

Roberts: Weren’t you intrigued by the thought that with cinema the spectator stands still while time progresses?

Duchamp: Yes, yes, there is an inexorability about time, but you do not have to be an artist to feel it. What are the poet’s words, “At my back I always hear, Time’s winged chariot hurrying near . . .?” That is too simple. I may die tomorrow. It doesn’t concern me. But the experiments of Muybridge and Marey at the time did interest me. Photochronography they called it; the fencing man or the galloping horse presented in successive images. These photochronographs gave me the idea how to put movement into a picture, as in, for example, Nu descendant un escalier.

Roberts: And you considered Nude Descending a Staircase to be your first contribution?

Duchamp: And it was really the introduction of movement per se as the motive for painting. I considered it a real achievement. An amusing achievement at least.

Roberts: Your original inspiration for Nude, then, was ideatic rather than visual.

Duchamp: “Ideatic,” what is that? Is that a word?

Roberts: I don’t know if it is. I think I made it up, but it means . . .

Duchamp: I know exactly what it means. I like it. It is a good word. But to answer your question, before the Nude my paintings were visual. After that they were ideatic . . .

My hand became my enemy in 1912. I wanted to get away from the palette. This chapter of my life was over and immediately I thought of inventing a new way to go about painting. That came with The Large Glass.

Roberts: Why did you feel compelled to paint on glass?

Duchamp: The main point is the subject, the figure. It needs no reference. It is not in relation. All that background on the canvas that had to be thought about, tactile space like wallpaper, all that garbage, I wanted to sweep it away. With the glass you can concentrate on the figure if you want and you can change the background if you want by moving the glass. The transparency of the glass plays for you. The question of painting in background is degrading for a painter. The thing you want to express is not in that background.

Roberts: Can you explain why it remains unfinished?

Duchamp: Again it shows that I really didn’t care to finish it. It was too long and in the end you lose interest. I felt that sometimes in the unfinished thing there is more warmth that you don’t change or make any more perfect in the finished product. You see, the sketches for The Glass I did before, some in 1914, and there was no creativeness left in it for me; just a translation of something already created.

Roberts: Did you feel you had exhausted the possibilities?

Duchamp: No, no, far from it. It was only another page to turn and that is how I came to the idea of the “Ready-made.” As you know, in 1914, even 1913, I had in my studio a bicycle wheel turning for no reason at all. Without even knowing whether I should put it with the rest of my works or call it work.

Roberts: Isn’t that a paradox?

Duchamp: Yes it is a paradox and the wheel was the first one and not even named Ready-made at the time. I never named anything. It just happened to be master of you . . . like fire in the fireplace or anything moving. Again, the idea of movement, you see, just transferred from the Nude into a bicycle wheel, at the same time I was working on The Glass.

Roberts: What is a Ready-made?

Duchamp: A Ready-made is a work of art without an artist to make it, if I may simplify the definition. A tube of paint that an artist uses is not made by the artist; it is made by the manufacturer that makes paints. So the painter really is making a Ready-made when he paints with a manufactured object that is called paints. So that is the explanation, but when I did it, it was not at all intended to have an explanation. The iconoclastic part of it was much more important. Well, the Impressionists were iconoclasts for the Romantics and the Fauves were the same and again Cubism against Fauvism. So when I came along, my little idea, my iconoclastic gesture.

Roberts: Do you see this as an act of defiance?

Duchamp: There is that, but also there is a philosophical side to it. The de-deifying of the artist. Of lowering his status in society.

Roberts: This a strange position for an artist to hold, isn’t it?

Duchamp: It is paradoxical. It is almost schizophrenic. On one side I worked a very intellectual form of activity and on the other side de-deifying everything by more materialistic thoughts.

Roberts: Did you think of it as a cosmic joke that included everyone, including you?

Duchamp: It is very important for me to introduce humor, to doubt the seriousness of the work in a cosmic whole of the world. Our little corner of the earth is so small, especially today as we get to know more about it. And we have always been anthropocentric, a little idea to be mocked. And I did include myself in the joke. I wanted to get rid of the herd instinct in artists; to individualize, to singularize, is what every artist should do instead of going towards mass production as we do today.

Roberts: How do you choose a Ready-made?

Duchamp: It chooses you, so to speak. If your choice entered into it, then, taste is involved, bad taste, good taste, uninteresting taste. Taste is the enemy of art, A-R-T. The idea was to find an object that had no attraction whatsoever from the esthetic angle. This was not the act of an artist, but of a non-artist, an artisan if you will. I wanted to change the status of the artist or at least to change the norms used for defining an artist. Again to de-deify him. The Greeks and the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries thought of him as a worker, an artisan.

Roberts: Do you think yourself as being anti-art?

Duchamp: No, no, the word “anti” annoys me a little, because when you’re anti or for, it’s two sides of the same thing. And I would like to be completely—I don’t know what you say—nonexistent, instead of being for or against. If I have been blamed for anti-art, I am delighted to be blamed, because that was my intention in the first place, to do something that would not please everybody, to do something iconoclastic . . .

The idea of the artist as a superman is comparatively recent. This I was going against. In fact, since I’ve stopped my artistic activity, I feel that I’m against this attitude of reverence the world has. Art, etymologically speaking, means “to make.” Everybody is making, not only artists, and maybe in coming centuries there will be the making without the noticing.

Roberts: Do you feel that the act of creating a Ready-made is an act of art?

Duchamp: I wouldn’t say so, no. The fact they are regarded with the same reverence as objects of art probably means I failed to solve the problem of trying to do away entirely with art. It is partly perhaps because I have only a few Ready-mades. If I can count 10, 12 gestures of this kind in my life, that is all. And I’m glad I did now because this is where the artists of today are wrong, I think. Must you repeat? Repetition has become the great enemy of art in general. I mean, formulas and theories are based on repetition.

Roberts: Do you consider your Ready-mades in the same order of achievement as your other works or do you think of them as being more trivial?

Duchamp: No, they’re not trivial, for me at least. They look trivial, but they’re not. On the contrary, they represent a much higher degree of intellectuality. And the one I love most is not quite . . . it’s a Ready-made if you wish, but a moving one. By this I mean three meters of thread falling down and changing the shape of the unit of length. The Three Standard Stoppages, I prefer to call them. I was satisfied with the idea of not having been responsible for the form taken by chance. At the same time I was able to use it for other things . . . in my Large Glass, for example.

Roberts: Doesn’t this depending on chance betray a certain disdain for the mechanics of art?

Duchamp: I don’t think the public is prepared to accept it . . . my canned chance. This depending on coincidence is too difficult for them. They think everything has to be done on purpose by complete deliberation and so forth. In time they will accept chance as a possibility to produce things. In fact, the whole world is based on chance, or at least chance is a definition of what happens in the world we live in and know more than any causality.

Roberts: This chance method of measurement, as with the Stoppages, puts a severe strain on the laws of physics, doesn’t it?

Duchamp: If I do propose to strain a little bit the laws of physics and chemistry and so forth, it is because I would like you to think them unstable to a degree. Even gravity is a form of coincidence or politeness since it is only by condescension that a weight is heavier when it descends than when it rises. Right and left are obtained by letting drag behind you a tingle of persistence in the situation.

Roberts: Your experiments in mechanical drawing, then, are not based on any physical laws as, say, Leonardo’s were.

Duchamp: No, no, it was a reaction against the easy, splashing way. I was fighting against the hand, so to speak. Mechanical drawing was the closest thing I could use. This was a way to get a new idea without changing the means. From the bottom up. My approach to the machine was completely ironic. I made only the hood. It was a symbolic way of explaining. What was really beneath the hood, how it really worked, did not interest me. I had my own system quite tight as a system, but not organized logically. My landscapes begin where da Vinci’s end. The difficulty is to get away from logic.

Roberts: How do you reconcile your anti-mechanical ideas with your interest in chess?

Duchamp: In my life, chess and art stand at opposite poles, but do not be deceived. Chess is not merely a mechanical function. It is plastic, so to speak. Each time I make a movement of the pawns on the board, I create a new form, a new pattern, and in this way I am satisfied by the always changing contour. Not to say there is not logic in chess. Chess forces you to be logical. The logic is there, but you just don’t see it.

Roberts: The chocolate machine which appears in The Large Glass . . . ?

Duchamp: Appears in many places. Always there has been a necessity for circles in my life, for, how do you say, rotation. It is a kind of narcissism, this self-sufficiency, a kind of onanism. The machine goes around and by some miraculous process I have always found fascinating, produces chocolate. Chess, on the other hand, involves a purely Cartesian exercise or the decision you have to make is of a different order and the result is of a different order. In art I came finally to the point where I wished to make no more decisions, decisions of an artistic order, so to speak. In chess, as in art, we find a form of machines, since chess could be described as the movement of pieces eating one another.

Roberts: It seems that you came early on to a definition of your role as an artist.

Duchamp: In the olden days, when the artist was still a pariah and a bum, the resistance of society to his way of life would bring about a meaningful explosion within himself. Provided he had something to say. It may be that great art can only come out of conditions of resistance, out of a state of war which forces the artist into an attitude of dedication that is almost religious and does not need the acceptance of society. In France there is an old saying, “Stupid like a painter.” The painter was considered stupid, but the poet and writer very intelligent. I wanted to be intelligent. I had to have the idea of inventing. It is nothing to do what your father did. It is nothing be another Cézanne. In my visual period there is a little of that stupidity of the painter. All my work in the period before the Nude was visual painting. Then I came to the idea. I thought the ideatic formulation a way to get away from influences.

Roberts: Do you think of yourself, then, not only as an artist, but as an acute observer and commentator on La Comedie Humaine?

Duchamp: No, no; observer, yes, but commentator, no. I’m nothing else but an artist, I’m sure, and delighted to be. And all these things that, you know, happened to me during my life, you become . . . the years change your attitude and I couldn’t be very iconoclastic any more.

[ad_2]

Source link