[ad_1]

The number of police officers stationed in schools has increased in recent decades in response to a devastating wave of school shootings like those at Columbine High and Sandy Hook Elementary. But when police walk the halls, Black children are disproportionately arrested, often for low-level offenses, contributing to a cycle called the school-to-prison pipeline.

Now, some activists are hoping that the protests against police brutality and racism roiling the country could be a turning point in efforts to dial back this kind of school security.

In Minneapolis, where protests exploded after a police officer killed local resident George Floyd, the school board voted Tuesday evening in favor of a resolution to cut ties with the police department. Before the vote, board member Josh Pauly told HuffPost that he has already heard from representatives in school districts in “Arizona, North Carolina, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Washington, Oregon, New York, and Illinois” asking for support in crafting a similar resolution. In Denver, a school board member told HuffPost that he has plans to introduce a comparable resolution as well.

After years of non-stop growth in the number of police in schools, even amid high-profile incidents of police brutality against students, “this conversation feels unprecedented,” said Jonathan Stith, national director of the nonprofit Alliance for Educational Justice, which advocates against the presence of police in schools.

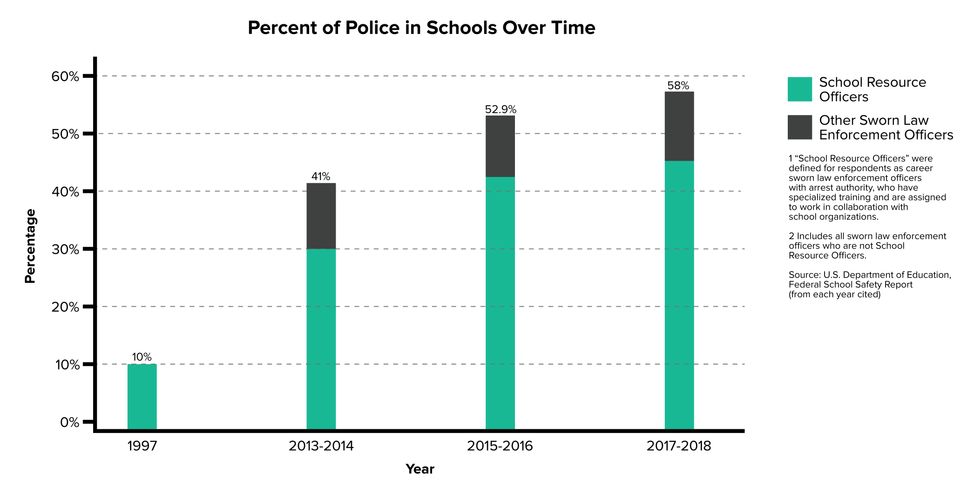

Overall crime in schools has decreased over the last two decades, mirroring larger societal trends, but the amount of security has skyrocketed. In 1997, only 10% of schools employed police officers. By 2017, that number had increased to 58%.

Members of the Minneapolis Public Schools board announced the proposed resolution last Friday, four days after a white police officer pressed his knee against Floyd’s neck for nearly nine minutes, killing the 46-year-old Black man and sparking a firestorm across the nation.

The Minneapolis Police Department currently partners with the school district to place 11 officers in schools, costing the district over $1 million, according to Minnesota Public Radio. That contract was up for renewal when Floyd was killed. School board members who already planned to vote no on renewal decided to take it a step further, crafting a resolution that will remove officers from city schools. The local teachers union endorsed the move.

“MPS cannot align itself with MPD and claim to fight institutional racism. We cannot partner with organizations that do not see the humanity in our students. We cannot be neutral in situations of injustice,” Pauly told HuffPost in an email. “Hopefully this can be a small step towards the dramatic changes that are needed in our city and beyond.”

In the past few years, serious conversations surrounding the impact of police in schools have occurred after high-profile incidents of officers assaulting children, like when a police officer was recorded knocking down a student and dragging her at Spring Valley High School in South Carolina.

But this particular moment feels different, said Stith, whose organization has been organizing around this issue since that 2015 incident.

“We’re excited and nervous at the same time,” said Stith, who said he has heard from a number of districts looking to take action. “So much research basically says every time a police officer steps into a school, it becomes a prison.”

In Denver, the power of school police officers is already regulated by the district: These cops are not allowed to handcuff students in elementary school. But in the wake of recent events, the school board there may go a step further.

Board member Tay Anderson told HuffPost that he believes he has the support of the majority of the board to reconsider the district’s contract with Denver police. He wants to see the money the district would typically allocate to the contract go to mental health resources instead.

Anderson graduated from the district’s schools in 2017 and ran for the school board on a promise to eliminate the district’s contract with the police department. But he found it was a touchy issue for some community members, who supported movements like Black Lives Matter but felt it was necessary to keep police patrolling school hallways. He’s hoping that mentality could soon change.

“We can call cops to our buildings as needed,” Anderson said. “There’s no need to have them for a specific presence in our schools.”

In Chicago, the local teachers union ― one of the largest in the nation ― recently called for the board of education to cancel its $30 million per year contract with Chicago police and direct the money to emergency counseling and support for students in crisis. In 2019, school resource officers, another name for school cops, were caught on video punching, Tasing and dragging a 16-year-old Chicago student down stairs.

Union leaders are pessimistic that their calls will make a difference. The board of education isn’t elected. Members are appointed by the mayor, who union leaders see as in bed with police forces.

“In a district that is 90% students of color, over 80% free/reduced-price lunch, in a city that is violent, we would prefer trauma supports, social workers, school psychologists,” said Stacy Davis Gates, vice president of the Chicago Teachers Union.

The numbers of police officers in schools have spiked in response to devastating school shootings, starting with Columbine in 1999 and most recently in Parkland, Florida, in 2018. Both Democratic and Republican presidential administrations have contributed to that increase. After the Sandy Hook massacre in 2012, President Barack Obama helped funnel federal money to school districts to use for hiring cops. After Parkland, President Donald Trump did the same.

Data shows that Black and brown students often bear the brunt of this increased policing. When cops are in schools, students ― especially Black students ― are more likely to get arrested or referred to local law enforcement, even for low-level offenses like vandalism and fights without a weapon. Black students also more likely than other students to attend schools with more school security officers than mental health workers.

According to Alliance for Educational Justice data, dozens of students have been assaulted by cops in schools over the years. A previous HuffPost investigation found that since September 2011, children have been Tasered by school cops in at least 143 incidents. Last September, a 6-year-old child in Florida was arrested by a school police officer during a temper tantrum.

Research on whether cops make schools tangibly safer remains mixed. Schools with police officers are more likely to go through regular safety checks and have emergency plans in place. While a 2013 report from the Congressional Research Service noted it makes logical sense that a school cop could deter school shootings, research hasn’t addressed that issue.

The National Association of School Resource Officers (NASRO) is the main organization helping to train cops to work in schools ― but not all districts require officers to attend such training and some offer their own. In 2016, HuffPost attended a weekend of NASRO training and found that most classes focused on preparing officers for rare occurrences, like school shootings or terror attacks.

The group’s executive director, Mo Canady, maintains that with the proper training, school resource officers can enhance a school community, ideally building positive relationships between students and law enforcement while protecting the school from threats.

“Generalization is unfair to any segment of our population, including members of individual organizations or professions. In other words, we do not believe in forming opinions about any large group based on the behavior of a few members,” said a statement from Canady.

He said that NASRO “abhors racism” and works to tackle racism by providing implicit bias training for officers.

Canady also noted that the Denver and Minneapolis school districts “choose not to send all SROs to NASRO courses but instead provide education from other sources. … It is possible, therefore, that significant policing issues exist in such communities.”

In a statement before Tuesday’s vote, Deputy Chief Erick Fors of the Minneapolis Police Department said that the relationships the department has built in schools “were impactful not only for the students and staff, but for the officers who had a calling to work with our youth through mentorship and engagement.” The Denver Police Department did not respond to a request for comment.

Janaan Ahmed, a 17-year-old recent graduate of Minneapolis Public Schools, said that student activists have made clear their disdain for constant policing at school and that they have been questioning why it took another police killing for the issue of school cops to gain momentum in the district.

Ahmed grew up just blocks away from where 24-year-old Jamar Clark was shot and killed by police officers after a dispute at a party in 2015. Seeing cops in the cafeteria, with a gun and Taser on their belts, can feel menacing, she said, making a normal day at school feel militarized. She said students at her school rarely had relationships with the SROs ― they were too afraid.

“Police are systematically lynching Black and brown people in our neighborhoods and our schools have the audacity to bring police officers in our schools?” Ahmed said.

According to Canady of NASRO, the goal of school policing programs is to “bridge the gap between law enforcement and youth, building positive relationships that can last lifetimes, while helping to protect schools from a wide variety of threats.”

Indeed, Ahmed said she had seen instances of school cops building positive relationships with students in her district. She pointed to a high school where an SRO doubles as the high school coach, often showing up to community events and mentoring students. He’s someone students look up to.

But she said that individual could still play a positive role in the school, without a badge.

“He can still be a community member without representing an institutionally racist system,” said Ahmed. “We are not talking about individual cops, we are talking about an institution.”

The story has been updated to note that the Minneapolis school board voted to terminate its contract with the Minneapolis Police Department.

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link