[ad_1]

In 2010, a small group of Muslim and Jewish women in New Jersey began meeting in one another’s homes, drawn by the prospect of working in solidarity to combat the hatred that each group faced.

Years later, the Sisterhood of Salaam Shalom has more than 3,000 women participating in 170 chapters in the U.S. and Canada. During these meetings, members spend time getting to know each other. They learn about similarities in Judaism and Islam. They celebrate holidays and life events together.

Recently, they’ve also been grieving the rise of white nationalist violence and planning how they will respond to both anti-Semitism and Islamophobia.

Executive Director Sheryl Olitzky said the Sisterhood is based on a simple premise: “It’s really easy to hate someone you don’t know. But when you know them, it’s difficult, and when you care about them, it’s impossible.”

A new survey is offering data on something that Olitzky and other American Jewish and Muslim leaders have been insisting on for years: that the stereotypes that paint these religious groups as “natural enemies” don’t reflect what’s actually happening.

The American Muslim Poll 2019, a research project from the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding (ISPU), suggests that American Jews and Muslims have much more in common than is often assumed.

Both groups are minorities in the U.S. who report facing religious discrimination. They are both becoming increasingly anxious about the threat white supremacists pose to their communities and houses of worship. They tend to vote for Democrats, and they are more likely to be educated and urban.

All these factors increase their chances of meeting. And the ISPU study suggests that once American Jews and Muslims meet each other, they become more than just acquaintances ― they become close friends and allies.

“These findings fly in the face of the dominant narrative that paints Muslims and Jews as natural enemies,” Dalia Mogahed, director of research at the ISPU, told HuffPost. “The data paints a different picture, one of two communities facing a common threat and who are by far the most likely to know and like each other. The story we tell about these communities should start reflecting this reality.”

The ISPU is a research organization that seeks to offer insight on the lives of American Muslims. Its January 2019 survey of 2,376 people was conducted among Muslims, Jews, Catholics, Protestants (white evangelicals in particular), and unaffiliated Americans.

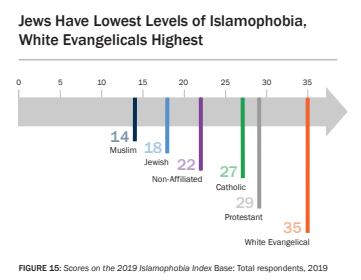

Collaborating with Georgetown University’s The Bridge Initiative, the ISPU attempted to measure the extent to which the American public endorses anti-Muslim tropes. The resulting tracker, dubbed the National American Islamophobia Index, analyzes the level of agreement religious groups had with the following five stereotypes about Muslims.

A. Most Muslims living in the United States are more prone to violence than others.

B. Most Muslims living in the United States discriminate against women.

C. Most Muslims living in the United States are hostile to the United States.

D. Most Muslims living in the United States are less civilized than other people.

E. Most Muslims living in the United States are partially responsible for acts of violence carried out by other Muslims

Compared to all the non-Muslim faith groups surveyed, Jewish Americans were the least Islamophobic, meaning they were most resistant to accepting those negative stereotypes about Muslims. On the other hand, white evangelical Protestants scored the highest on the Islamophobia Index.

Separate from the index, the ISPU asked participants whether they had an overall “favorable, unfavorable, or no opinion” about different religious groups. Jews and Muslims had similar responses to this question, with 45% of Muslims saying they had favorable opinions on Jews and 53% of Jews saying they had favorable views about Muslims.

Notably, Jewish Americans had significantly better opinions about Muslims than they did of white evangelicals. While 75% of white evangelicals had favorable opinions of Jews, only 25% of Jews returned the positive sentiment.

American Jews and Muslims also appeared to have similar thoughts about President Donald Trump’s attempts to restrict immigration through executive orders targeting primarily Muslim majority countries. Trump first proposed an outright ban on Muslims entering the country while campaigning in 2015, and, although the president has claimed otherwise, many Muslim leaders still think of his efforts as a “Muslim ban.”

The ISPU sought to measure whether political candidates’ support or opposition to the Muslim ban would have an effect in the voting booth. Sixty-one percent of Muslims and 53% of Jews said that a candidate’s endorsement of the Muslim ban would decrease their support for that individual. White evangelicals were the most likely religious group surveyed to say the opposite, with 44% saying a candidate’s endorsement of the Muslim ban would actually increase their support for that candidate’s run for office.

Olitzky believes American Jews feel a “moral responsibility” to protect people fleeing violence.

“Jews, because of their horrific past, know what it is like to not be welcome in any country, to not be protected from any country,” Olitzky said, specifically thinking about how Jewish refugees were treated during the Holocaust. “They feel the strongest responsibility so that this should never happen to anyone else.”

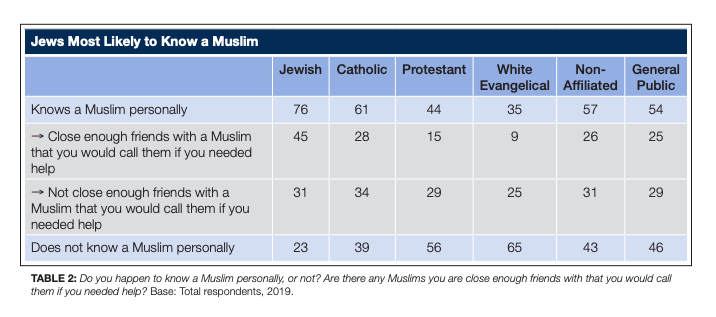

Researchers also discovered evidence of strong social ties between American Muslim and Jewish communities. About 53% of the general public reported knowing an American who is a Muslim, with white evangelicals being the least likely to say the same (35%). But 76% of Jews reported knowing a Muslim. And within that subset, 45% said they were close enough friends with a Muslim to “call them if you needed help” ― a much higher percentage than the other religious groups surveyed.

That closeness might help explain why American Jews have such positive views of Muslims. Political scientists have long argued that knowing someone from a specific community is associated with more positive views of that community. The ISPU analysis revealed that knowing a Muslim personally is a “protective factor” against Islamophobia.

“When a Muslim is a close friend, Islamophobia is further reduced,” the researchers state.

These strong social ties are reflected in a number of joint initiatives that Muslim and Jewish leaders are creating. In addition to the Sisterhood, there are groups like NewGround, a Los Angeles-based community-building organization that connects Jewish and Muslim professionals and high schoolers. There’s also the Muslim-Jewish Advisory Council, a collaboration between the American Jewish Committee and the Islamic Society of North America.

Aziza Hasan, NewGround’s executive director, told HuffPost that the ISPU’s findings confirm what she’s experienced while leading the interfaith organization.

“While Muslims and Jews share similarities and religious teachings, living as religious minorities in the United States also deeply connects our communities with shared common experiences,” Hasan said.

Olitzky said that the biggest issue that tends to cause divisions among Muslim and Jews today is the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Sisterhood chapters are purposeful about how that topic is addressed, sharing resources that teach participants how to engage in difficult conversations, listen with compassion and focus on building relationships with fellow members first.

Even with those political differences, Olitzky said that Muslim and Jewish women in Sisterhood chapters have found many commonalities. They face similar challenges in the workplace, for example, when it comes to observing holidays or fasts that most of their co-workers don’t partake in.

“It’s not easy being a Jewish or Muslim woman of faith in a country that is really navigated by a calendar, by dietary habits, by values that aren’t necessarily the same as yours,” Olitzky said.

In addition, Muslims and Jews also share experiences of being targeted for their faith. Of the religious groups surveyed, Muslims were the most likely to report experiencing religious discrimination (62%). Jewish Americans were the second most likely to say the same, with 43% reporting religious discrimination.

Jewish and Muslim leaders are both concerned about a rise in white nationalist violence. Mogahed, of the ISPU, said that Jews and Muslims are “natural allies” because they face this common threat.

Hasan said that she believes anti-Semitism and Islamophobia often go hand in hand. She pointed out that the shooter accused of killing 11 Jews at a Pittsburgh synagogue last year was angry at a Jewish nonprofit for helping Muslim refugees resettle in the U.S. The man accused of opening fire at a Poway, California, synagogue last week was reportedly inspired by the New Zealand mosque massacre and is suspected of setting a fire at a mosque last month.

“The pattern we find is that where there is anti-Semitism, there is often Islamophobia as well,” Hasan said. “While our shared trauma has brought our communities together, our response of solidarity and allyship has bonded us.”

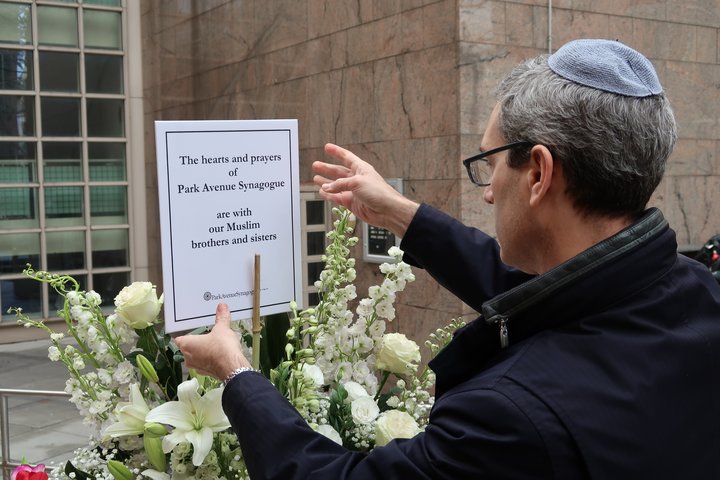

After the Pittsburgh shooting, Muslim worshippers raised thousands of dollars for the victims. Months later, Jewish groups in Pittsburgh raised funds for victims of New Zealand’s mosque shootings.

“Through the grief and the pain of this past year, one continual source of inspiration and strength has been the way our communities continue to show up for each other,” Hasan said.

The ISPU survey was conducted through telephone and online interviews. The survey has a margin of error of +/- 4.9% for Muslims and 7.6% for Jews and +/-3.6% for the general population.

[ad_2]

Source link