[ad_1]

Maria Goretti was just 11 years old in 1902, when she was murdered while defending herself from a would-be rapist. Alessandro Serenelli, a young man who lived near her family in the Italian town of Le Ferriere, had been pestering her for sex for some time, and had decided to kill her if she refused again. Though he threatened her with a 10-inch awl, she continued to resist, yelling “God does not wish it!,” even as he began to stab her.

She died of her injuries a day later. Serenelli later confirmed that he had not penetrated her ― you know, aside from the 14 stab wounds he inflicted on her with the awl. In short, upon her death, Maria remained a virgin. In 1950, she was sainted.

There is, in truth, no shortage of girls and women who have been murdered by sexually predatory men. What set Maria Goretti apart was that she had successfully defended her hymen with her life. She became a patron saint of rape victims, who, ironically, was never a victim of rape.

In my Catholic high school, in the early aughts, St. Maria was a role model. Some other Catholic school alumni I’ve spoken to in recent weeks also remember her chaste figure from their studies ― a popular subject for dress-up-as-a-saint days. She died at middle-school age, making her a perpetual peer of adolescents. “Often [a Confirmation name] was chosen because of a saint you really admired,” remembered a woman who went to school in St. Louis, Missouri. “Maria, for Maria Goretti, was by far one of the most popular Confirmation names.”

My school went so far as to name our chastity club after her, the St. Maria Goretti Club, which the theology faculty encouraged students to join. At that age ― a prickly but impressionable teenager ― I should have been low-hanging fruit for such a club. I was a virgin (both by choice and by circumstance, the circumstance being that no one was asking), and I planned to remain so until marriage (even if, hopefully, someone did start asking). A decade of Catholic schooling had stuffed me full of doctrine and values, and I eagerly rationalized positions I’d later come to find repellent. I believed that faith in God demanded sacrifice, even martyrdom. I believed that protecting innocent life might mean carrying a child to term even if it endangered me, even if the pregnancy was the result of a rape, because that baby hadn’t chosen to hurt me.

But a chastity club named after an 11-year-old girl who was murdered by a sexual predator ― the very concept broke something in my faith. To me, the chastity club was an overstep, a slip-up that tugged the veil off the Gothic underbelly of Catholic womanhood. I couldn’t fathom why the church would encourage me to die rather than allow a penis into my vagina.

This wasn’t about protecting innocents, or making virtuous personal choices, I thought; it was a near-complete conflation of women’s intact hymens and our goodness, a value system in which I would be preferred dead rather than a rape survivor.

The Brett Kavanaugh/Christine Blasey Ford hearings, steeped in invocations of pious Catholic boyhood and plausibly deniable misbehavior, raised a lot of ghosts for American women. I didn’t expect any ghosts to be raised for me; I’ve been lucky to never experience anything like what Blasey Ford did that night in 1982. But when she recalled the laughter at her expense ― “indelible in the hippocampus” ― and the hand over her mouth as two boys attacked her, the images felt familiar somehow.

After a childhood of Sunday mornings spent at Mass and school days with regular prayer time, the first time that I really became conscious of the hatred for women encoded in Christian tradition was in middle school. A family friend gave me a little white leather Bible with gold-edged pages for my confirmation, a milestone meant to signal your considered adult decision to enter the church. High on my new religious maturity, I decided to read a chapter of the Lord’s Word every night ― not Bible stories for children, but the Book itself.

Growing up female and Catholic often means internalizing, or at least conveniently ignoring, a millennia-old edifice of anti-woman doctrine, scripture and lore.

I expected transcendence, but stumbled, as if through a wrong passageway, into horror. Those Bible stories for kids’ anthologies, I quickly realized, had skipped over or heavily edited tales of casual brutality toward and sexual exploitation of women, and the laws that enabled it. In Deuteronomy, for example, I learned that if a man rapes a betrothed virgin in the country, the man should be killed for denying another man his promised bride. If he does so in town, the woman must die too; she didn’t scream loudly enough for rescue, so she must have been complicit. I remember reading that passage vividly ― the tissue-thin page, the matter-of-fact words, my queasy confusion.

Now, thinking of Christine Blasey Ford’s story of struggling with her assaulter’s hand clamped over her mouth as their friends partied nearby, I understand. If a woman’s cry for help is stifled and no one hears it, the rape itself can be erased, or it can become something else entirely: a shared sin, a mutual encounter.

Growing up female and Catholic often means internalizing, or at least conveniently ignoring, a millennia-old edifice of anti-woman doctrine, scripture and lore. When Deborah Ramirez came forward and alleged that Kavanaugh had exposed himself to her at a Yale dorm party, she recalled that, as a devout Catholic, she “wasn’t going to touch a penis until I was married,” that she felt “embarrassed and ashamed and humiliated.” I understood that fear, a gut-churning revulsion from the contamination of a man’s genitals. Much of this shaming is built into other Christian sects ― Deuteronomy doesn’t belong to the Vatican. But the church takes pride in being built on more than just the Bible, on its ancient traditions passed down in an unbroken line from the early days of the church.

The most purely Catholic part of my sex education, I always felt, was the invocation of the saints and the Virgin Mary. Evangelical and mainline Protestants might share certain tactics (purity rings, demonstrations in which a piece of duct tape gets less sticky after being stuck to several boys’ sleeves), but these semi-mythical beings are Catholicism’s special little way of recognizing who’s doing godliness better.

The women saints presented to us as role models were almost universally virgins, starting with the Mother of God. Catholics place a special emphasis on Mary, who is termed the Queen of Heaven and the subject of numerous apparitions to saints around the world. Though she was a mother and wife, Mary is held by the Church to have remained sexually chaste until death; this allowed her to stay pure of sin.

“My school taught me Mary died never having sinned in her entire life, and that she also never had sex in her entire life,” remembered Stephanie, who went to Catholic school in New York state. Though Catholic girls are often told that sex within marriage is Godly and beautiful, the implication of Mary’s lifelong purity is clear: Sex within marriage is at least just a teeny little bit sinful!

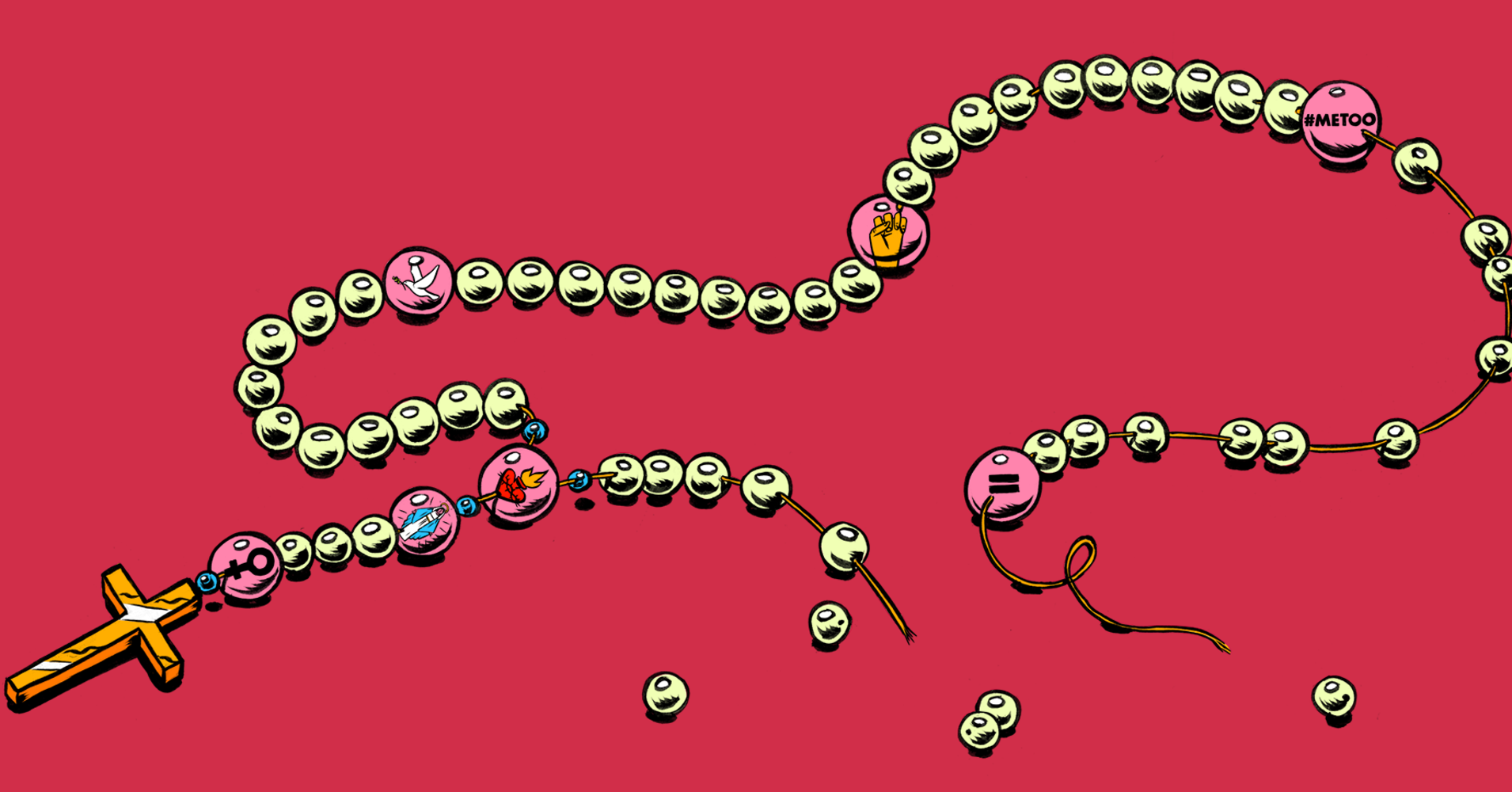

The church’s saints are meant to intercede on our behalf ― basically, you can pray to a saint, and the saint will use their superior clout to re-pray for you in the afterlife, as if you’re getting spiritually retweeted by a celebrity’s account. Saints are assigned as patrons to certain groups or concerns based on the circumstances of their lives and deaths; St. Blaise, a physician ultimately martyred by beheading, is the patron saint of throat ailments and choking, for example. St. Maria Goretti is not an anomaly in her patronage: The patron saints of rape victims are mostly not rape victims, but women who succeeded at being murdered instead.

Saints Agnes and Lucy were early Roman saints who took vows consecrating their chastity to God and refused the advances of pagan men. Because of their refusals, they were imprisoned, tortured, and ultimately killed. Both were sentenced to be held in brothels and raped, but Agnes was protected when God struck her attempted rapists blind, while Lucy could not be dragged to the brothel even by the force of a team of oxen.

The Blessed Antonia Mesina was just 16 when she was beaten to death with a rock while resisting an attempted rape in 1935. “At autopsy,” reads a hagiography on Savior.org, “the doctors determined that Antonia’s body had not been sinfully violated.” This should be irrelevant to the question of Antonia’s chastity, but it’s carefully noted, as if to guard against any suggestion that she was too impure for veneration.

The stain of the rapist’s sinfulness transfers so easily to the victim: Her lack of victimhood is also proof of her virtue. In this, as in so many victim-blaming narratives, lies the cruel implication that being raped is blameworthy in itself. Even if you fight, struggle, scream, a man’s success in raping you is also your sin, or at least your failure to be virtuous.

Not every Catholic high school has a chastity club named after St. Maria Goretti. The more I talk to other Catholic school alums, the more I suspect that mine operated at a heightened level of feverish devotion.

My high school had one of the most Catholic views in the country: The campus of the University of Notre Dame, green lawns and conservative theologians, lay across the street. The university is a staid religious institution, but not as much as my high school. To wit: when I was a junior, Bishop John D’Arcy ordered that the state’s then-governor, Catholic Democrat Joe Kernan, have his invitation to speak at my school’s commencement be withdrawn due to his pro-choice political stance. This year, Kernan was awarded Notre Dame’s prestigious Rev. Edward Frederick Sorin, C.S.C., Award.

I took a compulsory theology class each semester: Morality, Catholic Life, Sacraments. Sex featured in nearly all of them. We were told for many reasons not to have sex before marriage: Because within marriage it would be beautiful and godly; because we should save our virginity as gifts for our spouses; because we would get chlamydia and die; because God made orgasms for the sole purpose of procreation; because Mary could keep it in her pants and so could we.

I didn’t flirt because I was afraid. I didn’t dance too close at prom because I was afraid. I didn’t date because I was afraid. ‘I’m being good,’ I told myself, and the church agreed.

We were told explicitly to be like Mary and Maria Goretti, but all Catholics are told this implicitly. The saints are woven into the Church’s fabric, a tapestry of God-approved human figures. If we want to be good, Catholic women hear, we are to be more like these women. Our cultural understanding of morality has evolved somewhat with time, but the Church’s saints remain fossilized in amber.

In 1950, when Pope Pius XII canonized Maria Goretti, he praised how “[w]ith splendid courage she surrendered herself to God and His grace and so gave her life to protect her virginity,” and told parents to look to her as a model for “how to raise their God-given children in virtue, courage, and holiness.”

“What a shining example for young people!” applauded Pope John Paul II in a 2002 letter marking the centenary of Maria Goretti’s death.

Even apocryphal saints, like St. Ursula, a virgin martyr alongside her rumored 11,000 virgin martyr handmaidens, might be technically removed from the rolls but remain stubbornly bricked into the walls of the Church. They’re in the names of our churches and schools, evoked in literature and legend. They’re in our own names ― so many Catholics are named after saints, and even if we weren’t, there often is one anyway, like St. Clare, an acolyte of St. Francis of Assisi who fled a future as a wife to become a celibate nun. My friend recently told me that because of her middle name, Rose, she learned about St. Rose of Lima, who tried to disfigure herself so that she could evade marriage and keep her vow of chastity.

Turned one way, these are stories of heroically selfless women. Turned another, these are stories of women who were afraid of men, understandably and mortally afraid, or who at least acted like they were. Being a good girl and being afraid of men, for me, looked like very similar things.

So in high school, I didn’t go to parties with boys because I was afraid. I didn’t flirt because I was afraid. I didn’t dance too close at prom because I was afraid. I didn’t date because I was afraid. “I’m being good,” I told myself, and the church agreed. Prom chaperones high-fived me for saving room for the Holy Spirit, as if I’d done it out of extreme moral strength.

The Catholic Church asks its enormous, far-ranging congregation to swallow so much doctrine that seems patently absurd, callous or needless. For some, it’s an untenable amount. Even for those who remain in the church, so many disregard doctrines like the anti-contraception dictum (98 percent of sexually active American Catholic women of reproductive age have used contraception, according to a 2011 Guttmacher Institute report) that there’s a special term for the pick-and-choose faithful: cafeteria Catholics.

My schooling successfully convinced me that the religion was all or nothing. I tried to be all, but eventually, I chose nothing. By the time I was a year out of Catholic school, attending a secular university, I was no longer a practicing Catholic at all. I identified as lapsed, because once you’re baptized in the Church you are considered Catholic even if you stop practicing. I knew a lot of lapsed Catholics in college.

Lapsed suggests failure, defection; gym memberships or insurance policies lapse if we don’t make payments. It’s true, I haven’t been meeting my obligations as a Catholic. But the word I think of, when it comes to my Catholicism, is not lapsed, but latent. It’s there in my blood and my synapses, indelible in my subconscious mind, as if these stories were waiting silently for the right stimulus to stir them into consciousness again.

Despite having lapsed, I’d long been vaguely grateful to my Catholic education for keeping me on the straight and narrow, then for giving me something to rebel against. What I’m really thanking it for, I guess, is for encouraging my fearfulness; I’m offering gratitude for the sense it fostered in me that my sexuality didn’t belong to me, though any sins committed against it did.

Maybe I feel that these lessons protected me, or at least taught me to live in a world that does indeed operate by those rules. They just didn’t teach me to believe in them, in the end. They rigorously trained me and my female friends in the structure and logic of an ideology many of us would turn against with a precise fervor that only derives from familiarity.

I think of the hand clamped over the mouth. I think of Maria Goretti, just a little girl, crying out in anguish to her attacker, “God does not wish it.” Not “I don’t wish it.” What she wished is not what matters in this story. Maybe there’s another story in which it would be.

[ad_2]

Source link