[ad_1]

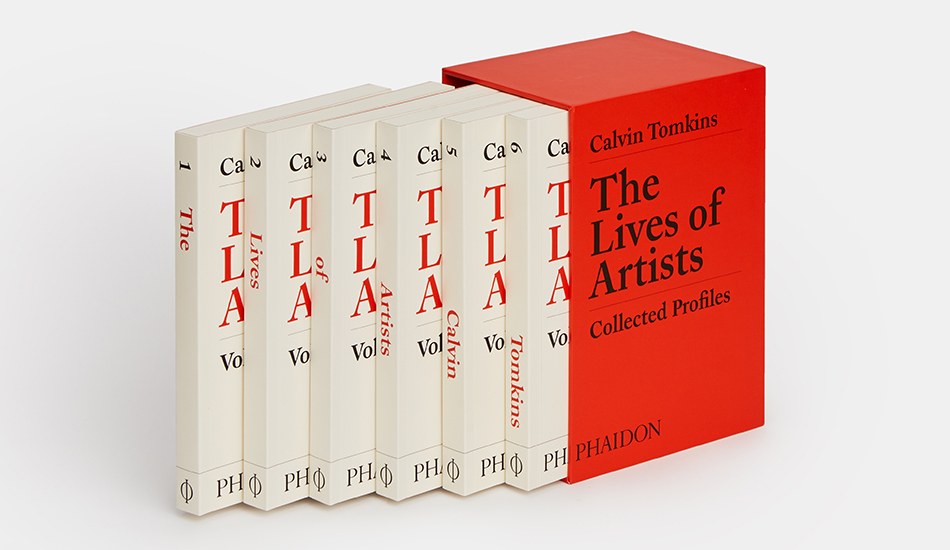

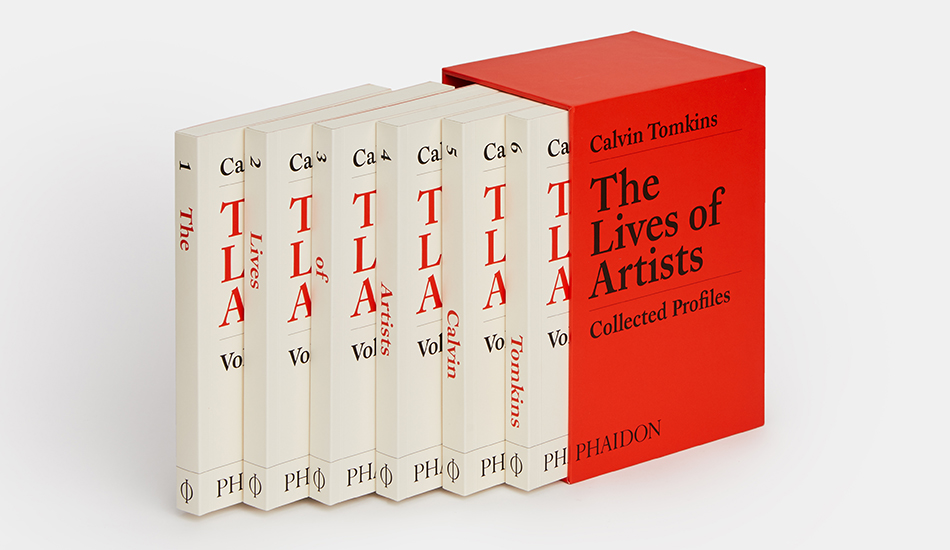

The Lives of Artists, a new boxed-set collection of profiles by Calvin Tomkins, brims with more than 80 stories.

COURTESY PHAIDON

“Art of the City” is a weekly column by Andrew Russeth that runs every Tuesday.

This year marks the 60th anniversary of Calvin Tomkins’s first artist interview. He was in his early 30s at the time, and working for Newsweek, when he was asked to go visit Marcel Duchamp. They met at the storied King Cole Bar in Midtown Manhattan. “I’d had about 45 minutes to prepare for it, so my questions were predictably dumb,” Tomkins writes in a preface to a new collection of his work, “but his answers were not. Everything surprised me.”

The rest is the stuff of legend. Tomkins would go on to become the premier chronicler of the age’s art scene, right up to the present, with the New Yorker publishing most of his artist profiles. “I knew very little about art, so my on-the-job learning curve was steep and haphazard, but the timing was close to perfect,” he writes. Things were about to get very interesting in the art world. Pop was on the horizon. The Castelli Gallery was 2 years old, and the Green was about to open.

Titled The Lives of Artists, the handsome new Phaidon set—six volumes in a fluorescent red case that recalls Sterling Ruby’s Desert X sculpture—comes in at about 1,600 pages and weighs a healthy 6 pounds. It comprises 82 articles, stretching from a 1962 adventure with Jean Tinguely to a sit-down with Vija Celmins that just appeared in August. An essential and highly pleasurable record of the era, it also amounts to a sprawling, lifelong investigation into what it means to be an artist. Why does a person become one? What is their role in society? How do they continue on?

There are not always straightforward answers—or any at all. In the 1970s, with Tomkins at her Ghost Ranch in New Mexico, Georgia O’Keeffe, then well into her 80s, recalls telling a friend at the age of 10 that she would become an artist. “I had no idea where that came from,” she says. “I just remember saying it.” Later in that decade, at the unveiling of his 101-foot-tall Batcolumn sculpture in Chicago as he sat alongside Second Lady Joan Mondale, Claes Oldenburg admits having had doubts about making public art. “One thing leads to another,” he says, “and you find yourself sitting on a platform like a politician.”

An indefatigable listener whose pieces regularly involve months of reporting, Tomkins has a remarkable talent for eliciting big reveals, or simply catching them when they come. Architect Philip Johnson concedes “we could have designed better buildings” at Lincoln Center, in a profile that doesn’t shy away from his fascist and Nazi period. And even while discussing her creatively fertile relationship with Alfred Stieglitz, O’Keeffe remarks, “Of course, you do your best to destroy each other without knowing it—some people do it knowingly and some people do it unknowingly.”

The robust length of many Tomkins pieces, especially early on, invites the reader to luxuriate in details and stories that might get cut nowadays. Buckminster Fuller uncorks one improbable stem-winder after another, alternately enervating and captivating. Romare Bearden tells about an eight-foot-long python that an “exotic dancer” brought to his studio one night, and shares that Hannah Arendt and her husband, Heinrich Blücher, encouraged him to stop dabbling in music and focus on painting. Robert Wilson, in an especially elegant profile that is intercut with a play-by-play of his hulking 1973 performance The Life and Times of Joseph Stalin, discusses giving a press conference in Yugoslavia where he repeated the word “dinosaur” for 12 hours while chopping an onion.

Even at their most obtuse and curmudgeonly (hello, Frank Stella!), Tomkins subjects are sympathetic. There are no takedowns, and only the rarest moments of disapprobation from the author. (Post-structuralism is “an exceptionally glum line of thought,” he writes at one point. He is also skeptical of the lasting relevance of Minimal and Conceptual art.) As New Yorker editor David Remnick says in an introduction to the box set, “He is the least academic writer imaginable, possessing no theories, no philosophies of art. But he sees magnificently, both the work and the creator.”

If there is one obvious oversight in this majestic anthology, Tomkins at least anticipates it. “The relative scarcity of women reflects, I’m sorry to say, the reality of the art world until quite recently,” he writes. That is true only insofar as women artists were not often present in art’s halls of power during the start of his career. They were certainly active.

This is a project devoted, fundamentally, to the winners of their times, a hall of fame that omits numerous women and nonwhite artists, whose stories Tomkins has taken up with a great deal more regularity in recent decades. One wishes he had more often gone in search of less lionized figures.

A lot has changed in Tomkins’s decades on the beat. For one, he notes that “the increasing flight of advertising money to other media forced cutbacks in the magazine’s page count.” His pieces have gotten shorter, though a solid percentage of his portraits still instantly rank as definitive when they appear.

It is easy to bemoan the state of arts journalism today, as periodicals fold, papers nix coverage of culture, and blue-chip galleries mount their own luxe editorial projects. The era of book-length magazine profiles is certainly over, and there is some sadness in that, but also a silver lining. As the art world has become vastly larger, more international, and more interconnected, enterprising digital outlets have emerged—like Topical Cream, Arts.Black, Sex, Dis, and innumerable podcasts—that cover a far wider range of subjects than the old media ever did.

“The great artist of tomorrow will go underground,” Tomkins’s lodestar, Duchamp, once said. Something similar is perhaps happening now in regard to art writing. One role of legacy outlets like ARTnews could be to try to piece together the innumerable fascinating things happening around the world, charting interplays between specific scenes and a mainstream, mass audience (whatever that is, exactly).

In any case, Tomkins’s prose exudes the sheer joy of writing about art: holding on tight as Stella blows past the speed limit in a sports car, or watching on, in Osaka, Japan, as inspired artists blithely burn through the budget for Pepsi’s pavilion at Expo ’70, or just sitting with an artist for many hours, trying to understand how they see the world.

Starting out, Tomkins writes, he aimed to keep himself out of stories, as a kind of reaction to New Journalism. Later, though, he changed his approach. “I eventually realized that being part of the action was more fun for me,” he says, “and probably for the reader.”

[ad_2]

Source link