[ad_1]

Details of work, from left, by Mahi Binebine, Samuel Fosso, and Lebohang Kganye.

LEFT AND RIGHT: COURTESY THE ARTISTS; CENTER: ©2013 SAMUEL FOSSO/COURTESY JEAN MARC PATRAS, PARIS

“I have oftentimes said that the future belongs to Africa, because it seems to have happened everywhere else already,” curator Okwui Enwezor stated in 2015, in one of many interviews on a subject he knows well. With such sentiment in mind, ARTnews looks to ten African artists whose work resonates right now. Their art ranges from films and sound installations to photographs and digital works. Some are interested in mining complex histories while others imagine new futures for the African continent—and the entire world.

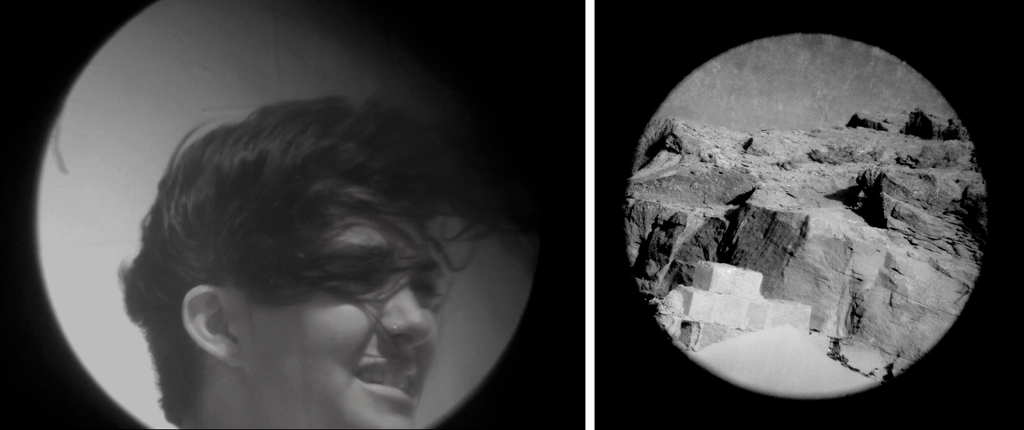

Heba Y. Amin, “The Pupil of the Mosquito’s Eye” (still), 2017, left; “35° 44′ 21.96″ N, 5° 53′ 26.38″ W Boukhalef, Tangier, Morocco” (still), 2018, right.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

Heba Y. Amin

Born in 1980, Cairo, Egypt; based in Berlin, Germany

In 2014, Heba Y. Amin went on a trip in which she traced a centuries-old trade route from Nigeria to Europe. In the process, she brushed up against power structures—the journey required 12 different travel visas—and engaged in what she called “bureaucratic intimacy,” or the forced act of giving personal information to authorities. “Crossing borders becomes an intimate act,” she said. Her travels became the basis for “The Earth Is an Imperfect Ellipsoid,” a body of photographs, sculptures, and videos from 2016 that meditate on the ways people and images are transferred around Africa and the Middle East.

Common among her other works (including some in this summer’s Berlin Biennale) is a special interest in how surveillance technologies—digital and otherwise—affect movement. Asked what she’s working on now, Amin said, “I am initiating a large-scale infrastructural intervention that proposes to sink the Mediterranean Sea and relocate it within the African continent.”

Frances Bodomo, Afronauts (still), 2014.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

Frances Bodomo

Born in 1988, Accra, Ghana; based in New York, United States

In Afronauts, a short film from 2014 by Frances Bodomo, a Zambian teenager with albinism prepares for a trip to the moon in the late 1960s. The girl is never shown in space, but the arid landscape looks alien in the film’s stark black and white cinematography. As in many of her other works, the notion of travel can be a metaphor for migration, and Bodomo knows transit: she was born in Ghana, raised in Norway and Hong Kong, and is currently based in New York.

While she doesn’t consider her work autobiographical, “I do make films to process murky or inexplicable experiences, so there is a clear link to my own memories,” she said. Her films navigate that murkiness. After debuting at the Sundance Film Festival in 2014, Afronauts charted an unusual course through the art world—most notably in an immersive-cinema exhibition at the Whitney Museum in New York. Bodomo is currently working on financing a feature-length version of the film.

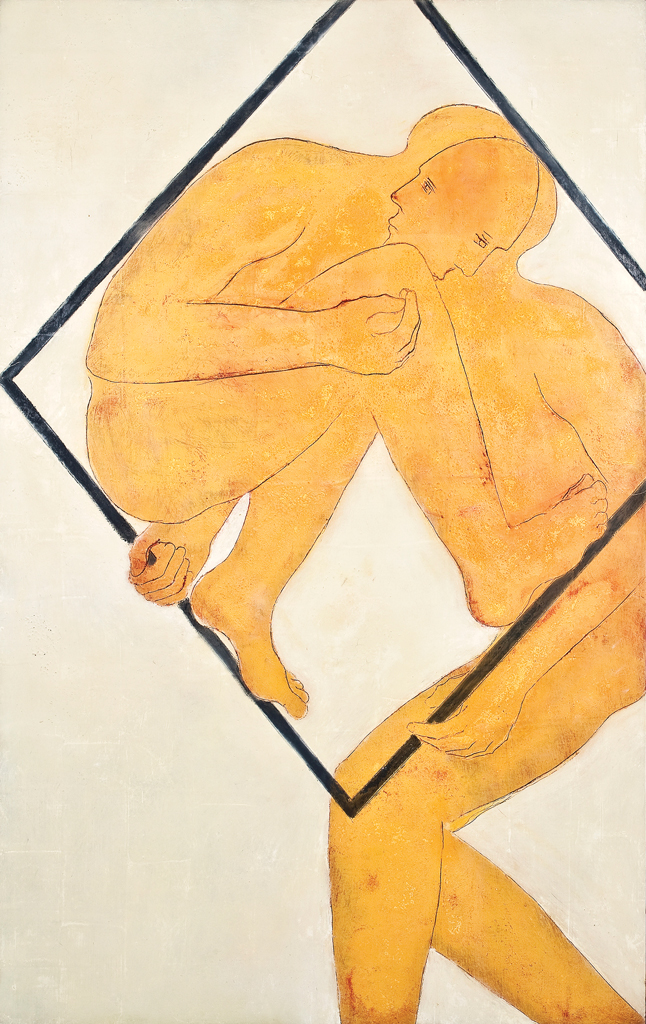

Mahi Binebine, Untitled, 2014.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

Mahi Binebine

Born in 1959, Marrakech, Morocco; based in Marrakech, Morocco

Known in his homeland and beyond as a novelist, Mahi Binebine has been steadily producing paintings and drawings in which thinly rendered nude figures are piled on top of one another, creating a cacophony of limbs and blank-looking faces. The works are minimal, with characters that appear to have neither gender nor emotion. They are strange, alluring visions that seem to address confinement and the stripping away of identity, though Binebine insists that they are simply “excuses to tell stories about humans.”

In some of his most recent works, there is a ray of hope—with subjects expanding beyond their claustrophobic circumstances, squeezing through boxlike forms, and kissing on bare floors. Binebine painted some of these images in blue—a color he has said signals liberty.

Samuel Fosso, Self-Portrait as Mao Zedong, from the series “Emperor of Africa,” 2013.

©2013 SAMUEL FOSSO/COURTESY JEAN MARC PATRAS, PARIS

Samuel Fosso

Born in 1962, Kumba, Cameroon; based in Bangui, Central African Republic, and Paris, France

In his gimlet-eyed photography, Samuel Fosso poses as characters—Mao Zedong, Angela Y. Davis, and Malcolm X—in line with a long tradition of performing for the camera. “When I began, I didn’t realize it was artistic work,” Fosso said of his portraits, which he began making in the 1970s as a teenager in the Central African Republic. It wasn’t until his work appeared alongside that of Malick Sidibé at the 1994 Rencontres de Bamako biennial that he regarded his photographs as art.

Fosso said he hopes he looks “around 50 percent” like the people he mimics in his portraits. But for his latest project, a typology in book form of 666 different facial expressions to be published later this year by Steidl, he emotes for the camera without any makeup or signs of disguise.

Lebohang Kganye, Ka 2-phisi yaka e pinky II, 2014.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

Lebohang Kganye

Born in 1990, Katlehong, South Africa; based in Johannesburg, South Africa

Lebohang Kganye embarked on “Ke Lefa Laka,” a multipart photo project, when her mother died. (The title translates from Sotho as “My Inheritance.”) In one part of the series, the artist superimposed her own image on top of her mother’s, creating what seem to be specters haunting the present from the past. Kganye said she hoped to summon her mother in a manner in which “she is me, I am her, and there remains in this commonality so much difference.”

Kganye attributed “Ke Lefa Laka” partly to the fallout of apartheid—how her family had to settle and resettle over the years—and also how images can be manipulated to tell new stories. Other of her photographs and films have combined personal stories with political events in South Africa. Her most recent work involves animations in which cutout versions of old photos move around. In one, a woman irons fabric while a train chugs past. With the woman’s face removed, viewers are left to fill in the details. “A family identity,” Kganye said, “becomes an orchestrated fiction and a collective invention.”

Gonçalo Mabunda, Untitled (Throne), 2017.

COURTESY JACK BELL GALLERY, LONDON

Gonçalo Mabunda

Born in 1975, Maputo, Mozambique; based in Maputo, Mozambique

Gonçalo Mabunda’s sculptures might look like artifacts—ceremonial masks, maybe, or ancient thrones—but they are made from disarmed AK-47s, pistols, rocket launchers, and rifles, their parts reassembled. The intention, Mabunda said, is “to transform something that was created for evil into something better. I try to create beauty out of burdened material.”

Such sculptures refer to the history of Mozambique, which from 1977 to 1992 was engaged in civil war. After the violence, Mabunda participated in an “Arms for Art” program that exchanged decommissioned weaponry for farming tools, and he has since become one of his country’s most closely watched artists—in 2015, he became the first Mozambican to show at the Venice Biennale. Now Mabunda has turned his attention to used metal, which he purchases from scrapyards or on the street. “I do not paint the metals. I use their natural colors,” he said. “I try to rescue a story I do not know.”

Mimi Cherono Ng’ok, Untitled, 2014.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

Mimi Cherono Ng’ok

Born in 1983, Nairobi, Kenya; based in Nairobi, Kenya

Golden yellows, milky blues, and smoldering reds feature in Mimi Cherono Ng’ok’s photographs, which often take the form of mysterious, dreamy landscapes and portraits. Her pictures are personal. “The photographs are like writing letters, journaling,” she said. “My photography is a world I’m inhabiting and creating simultaneously, constantly expanding and shifting.” While her sumptuous compositions might appear to have been carefully planned—in one from 2014, a shirtless man, shot from above, reclines on a floral bedspread with one arm slung over his face as though shielding himself from magic-hour sunlight—they are in fact barely mapped out before the shutter clicks.

“There’s a balance between making images on the fly and going back to places and objects I found interesting but didn’t have time to photograph,” she said of her work, which is in the Berlin Biennale this summer and will appear later this year in the Carnegie International in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. “Most of my preparation involves long walks, acclimating myself to the environment, sitting and watching spaces I’m in.”

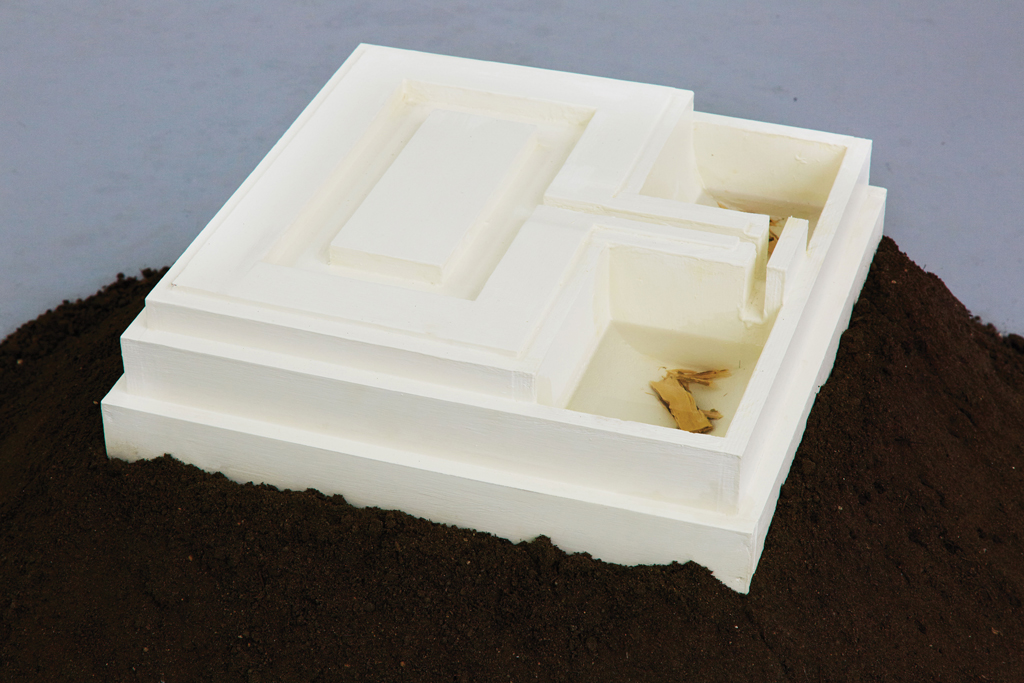

NTU, Ubulawu (detail), mixed-media installation, 2017.

COURTESY THE ARTISTS

NTU

Founded in 2015, Johannesburg, South Africa

Members of the collective NTU discuss their installations, which often combine distinctly African kinds of spirituality and digital technology, in terms that bridge biology, mysticism, and art history. “We’re drawn toward a methodologically expanded approach to science that is sensitive to subjective insight, raises questions around dominant realities, and serves the highest good of humanity and earth,” the collective said.

The group—Nolan Dennis, Tabita Rezaire, and Bogosi Sekhukhuni, all of whom also work solo—formed in 2015 around the creation of Nervous Conditioner.life.ntu.001 (2015), an installation involving an independent online network intended to allow users of color to surf the web without being monitored by corporations and governments. With its slick surfaces, the work resembles a politicized version of an Apple store display. NTU is now creating a piece centered on medicine and African metaphysical science in which the natural and supernatural coexist. “It’s stimulating,” the collective said, “to study the past and see oneself in one moment relative to another.”

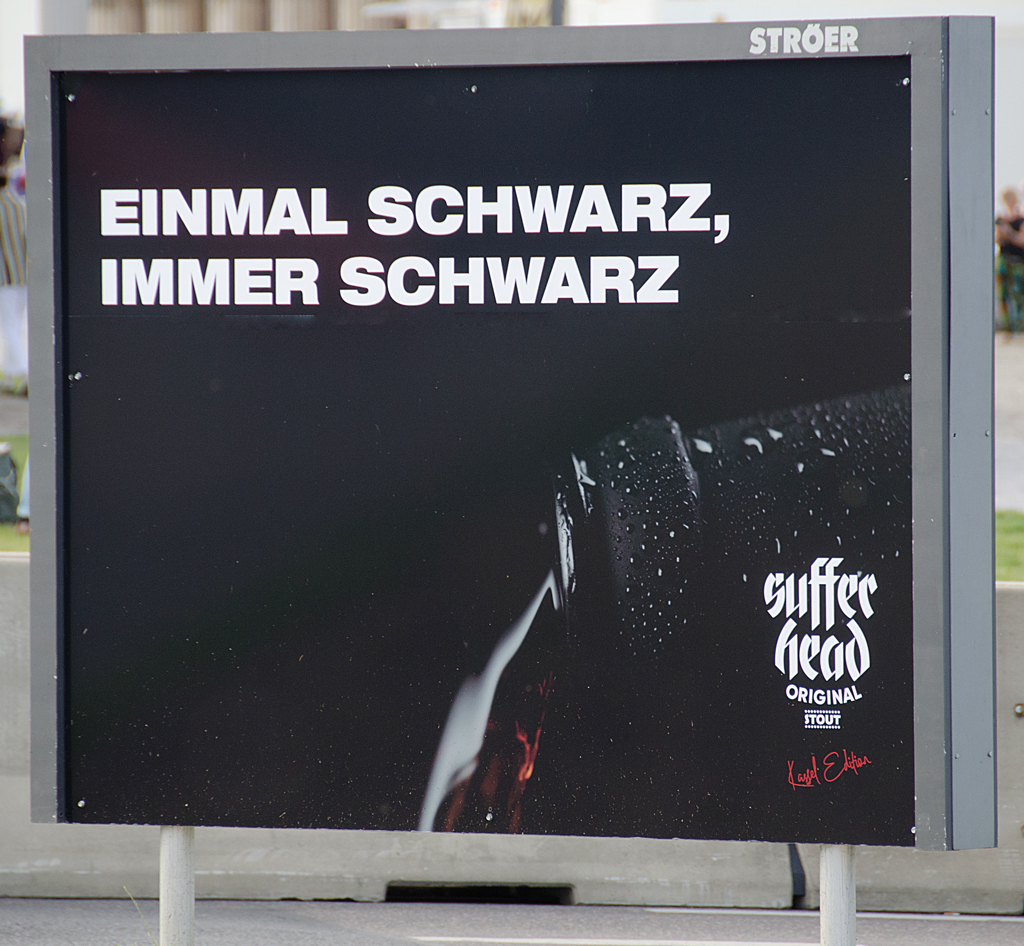

Emeka Ogboh, Sufferhead Original (Kassel Edition), 2017.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

Emeka Ogboh

Born in 1977, Enugu, Nigeria; based in Lagos, Nigeria, and Berlin, Germany

In Emeka Ogboh’s sound art, the aural remnants of crowded streets and bustling marketplaces summon the city he calls home. “My foray into sound art was facilitated by Lagos,” he said. “The megacity taught me how to listen, record, and analyze sound—the city made me a sound artist.” Ogboh’s work has been nominated for the Guggenheim Museum’s prestigious Hugo Boss Prize, and he participated last summer in Documenta 14 and Skulptur Projekte Münster. For the latter, he placed speakers inside a pedestrian tunnel and had a musician play the triamba, a percussion instrument, in tribute to the late New York street performer Moondog.

While there, Ogboh also brewed Quiet Storm, a beer that, its label claimed, was “fermented with the sounds of Lagos” and was made with “honey collected in the city of Münster.” As the artist explained, “I have an interest in how collective memories and histories are translated, transformed, and encoded into sound and food.”

(Ogboh ahelped ARTnews compile a three-hour playlist of music to accompany the Summer 2018 issue titled “Africa Now.”)

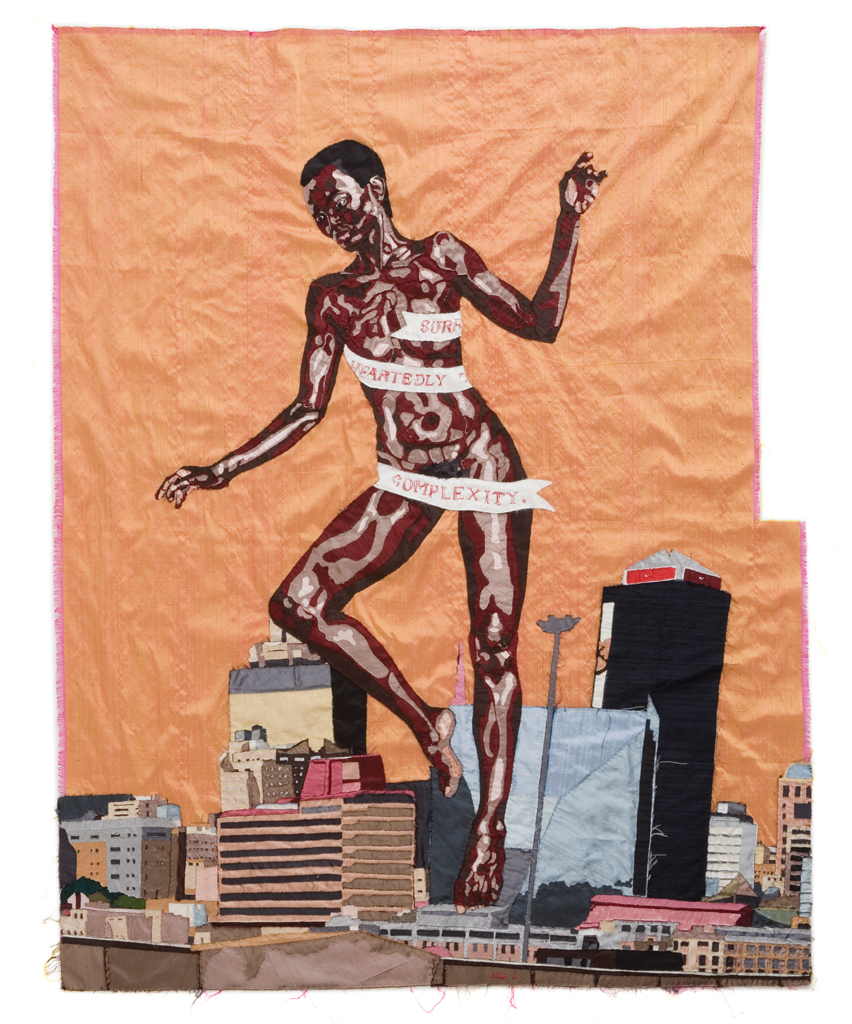

Billie Zangewa, The Rebirth of Black Venus, 2010, silk tapestry.

©BILLIE ZANGEWA/COURTESY AFRONOVA

Billie Zangewa

Born in 1973, Blantyre, Malawi; based in Johannesburg, South Africa

In The Rebirth of the Black Venus (2010), a tapestry by Billie Zangewa, a woman appears to levitate above an urban metropolis, her nude body wrapped in a white ribbon with one word notably covering her genitals: “COMPLEXITY.” Of her sewn pieces, the artist said, “historically, women have been exoticized, exploited, and silenced. I want to be a part of breaking the silence.”

As powerfully rendered as her characters’ bodies are the clothes they wear. Richly patterned robes, red checkerboard skirts, and indigo dresses figure in her tapestries, and her interest in clothing—and the lack thereof—owes to her fascination with the fashion world, in particular Ellen von Unwerth’s racy photographs of scantily clad models. In fashion, Zangewa said, fabric is often woven into shared narratives. “A collection tells a story, the fashion show tells a story, the photoshoot tells a story,” she said. “With my work, I, too, am telling stories.”

A version of this story originally appeared in the Summer 2018 issue of ARTnews on page 88 under the title “African Artists to Watch.”

[ad_2]

Source link